6.2.1 Mortgages – the risks

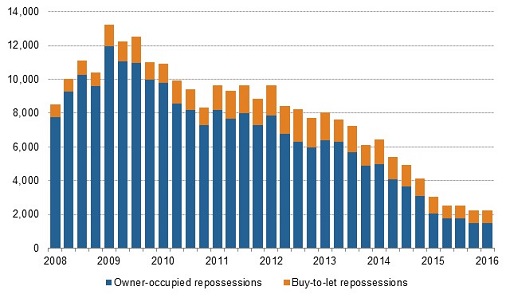

Figure 4 shows the numbers of properties in the UK that were repossessed by lenders between 2008 and 2016. This occurs when those buying a property with a mortgage find themselves unable to meet the repayments required.

The reality of repossessions demonstrates a key risk involved when buying a property. You have to ensure that you can always make your mortgage payments. If you cannot do so, you risk losing your home.

The pattern of repossessions also demonstrates the links between the housing market and the wider economy. The high points in the repossession cycles in the early 1990s and late 2000s occurred when the economy was in difficulty, with unemployment increasing or with interest rates at high levels. Unemployment and high interest rates are two reasons why households become unable to pay their mortgages. If either of these happens for a sustained period, repossession then takes place.

The lender will often allow some leeway involving a small number of missed payments, provided they are advised of what the borrower believes to be a temporary problem. However, if payments are missed for a sustained period the lender is likely to take action, including as a last resort repossessing the property.

While some pressure has been applied to lenders by the government to act with consideration when borrowers fall behind with their payments, at the end of the day a mortgage is a secured loan. If the repayments are not met, the security (that is, the property) will be taken by the lender.

One way of protecting yourself is to take out Mortgage Payment Protection Insurance (MPPI), also known as accident, sickness and unemployment insurance (ASU). This usually covers the repayment of interest (but not capital) if you are unable to work because of accident, sickness or redundancy. Typically, a period of up to two years’ cover on mortgage repayments is insurable, but because of exclusions this type of insurance is not suitable for everyone.

The government may also assist through schemes to help people stay in their homes, for example by switching to renting part or all of their home or, for those on certain benefits, through help with mortgage interest payments.

Will your investment plan pay off your mortgage?

Another risk is that the savings or investment vehicle used to pay off the principal sum in interest-only mortgages produces insufficient money. Investment policies sold in the late 1980s and 1990s were based on assumptions about future investment performance that turned out to be too high.

Low inflation and interest rates since the early 1990s, and the periodic weakness of certain of the world’s stock markets, mean that some borrowers are at risk of finding that the principal sum of their mortgage cannot be paid off by the proceeds from their investment product. This is particularly true if borrowers did not regularly review how much they were setting aside.

This highlights the importance of the ‘Stage 4 Review’ part of the financial planning process: in this case, reviewing the progress of the investment regularly and making adjustments if the investment is unlikely to repay the loan in full. Sellers of the investment products should advise you about this risk when you take out such a mortgage, and should follow up with regular re-projections of how the product is performing.

Options if your investment plan is under-performing

If the risk looks as though it will materialise, you have the following options:

- increase monthly payments on the investment product to increase the projected earnings by the maturity date of the investment

- increase savings by paying extra into a different investment product, which then supplements the original

- move to a repayment mortgage for some or all of the outstanding debt

- find additional resources when the mortgage reaches the end of its term; this could include borrowing again to meet the outstanding debt

- switch from the original product into another, although this is likely to incur penalties

- sell another asset or perhaps use a lump sum paid from a pension scheme.

Investment products can produce a return that exceeds the principal sum. Recent policies have seen projected shortfalls, but older policies have often produced returns in excess of the principal sum of the mortgage, since these benefited from the higher investment yields seen in the 1980s and the early 1990s, and from tax reliefs that have now been abolished.

Another risk is that of negative equity. House prices fell between 1989 and 1995, declined again during the period from 2008 until the start of 2013, and could do so again in the future.

Many of those who bought houses at the peak of the market found themselves in a situation of negative equity, where the size of the mortgage debt exceeded the market value of their property. Moving into negative equity is not critical if the borrower is still able to meet their mortgage repayments and does not have to move home.

However, if moving is necessary and house prices have fallen, there is the risk that the sale proceeds will be less than the amount owed on the mortgage. Either the shortfall has to be made up from other resources (for instance, savings or a loan) or it has to be added to the size of any new mortgage on a new property – provided the lender agrees to this.

Some mortgage lenders, particularly during the housing boom of the 2000s, offered mortgages of more than 100% of a home’s value. What issues should you consider before taking out such a mortgage?

For some people, this kind of mortgage will enable them to buy a property that they otherwise could not buy. However, anyone taking on a debt for a sum greater than a property’s value should be aware that they will immediately be in negative equity. This means that if they want to move home in the future, they will have to finance the difference between the total debt and the property’s value, or gamble on house prices rising.

A further risk of having a mortgage is that the mortgage ends up costing more than it needs to. It is possible, even if the best available mortgage was arranged at the time of purchase, that either circumstances have changed or other mortgage deals have become available – such as if a fixed rate product is taken out and interest rates subsequently fall.