1.3.2 Behind the scenes with Gaia

The Open University’s Department of Physical Sciences is involved in many different research projects, one of which is the Gaia satellite.

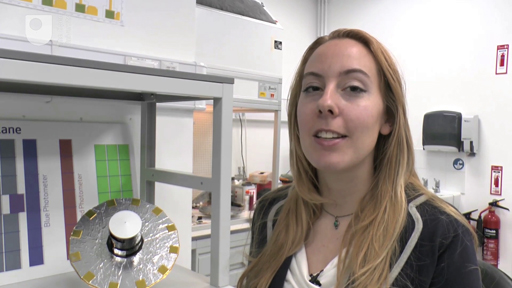

Ross Burgon is one of the scientists working with the Gaia project team. In the following video he talks to Phillipa about the research carried out in the Centre for Electronic Imaging (CEI) [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

Transcript

Next, you’ll have an opportunity to test your knowledge in the end-of-week quiz.