1.1 Structure–function relationships

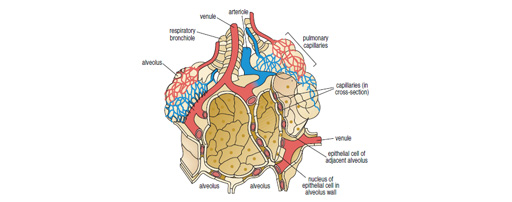

The cells within tissues are generally arranged to carry out the function of the organ most effectively. Consider the lung as an example.

The lung’s primary function is gas exchange. Red blood cells carry oxygen from the lungs to the other tissues and return carbon dioxide to the lungs. The physiology of the blood transport systems need not concern us here, but the relationship of the cells in the lung is optimised for gas exchange as shown in the diagram.

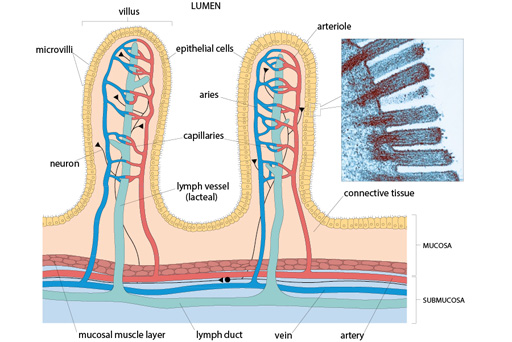

Another tissue that you have already seen is the gut. (Recall that the appearance of the gut varies greatly along its length, although the overall arrangement of the layers of cells is basically the same throughout.)

The main site for absorption of nutrients is in the intestine, which has a very large surface area, with numerous villi. The villi have a rich blood supply and lymphatic drainage; therefore, this region of the gut is particularly well suited for their function.

The rest of this week guides you through studying the structure–function relationships of a range of tissues, as grouped by the main functionalities we identified earlier. You will start by looking at secretion, before progressing on to movement, strength, excretion and communication.

As you learn to recognise each tissue, try to relate the histological appearance to the 3D structure of the organ and its underlying function.