3 Distinctions between hard and soft complexity

Systems thinking is very helpful in dealing with messy situations, wicked problems or frustrating puzzles where the overall complexity involved appears overwhelming. But what do we actually mean by complexity in this context and how can we deal with it effectively?

John Casti, a mathematical modeller and writer on complex systems, says that:

… when we speak of something being complex, what we are doing is making use of everyday language to express a feeling or impression that we dignify with the label complex.

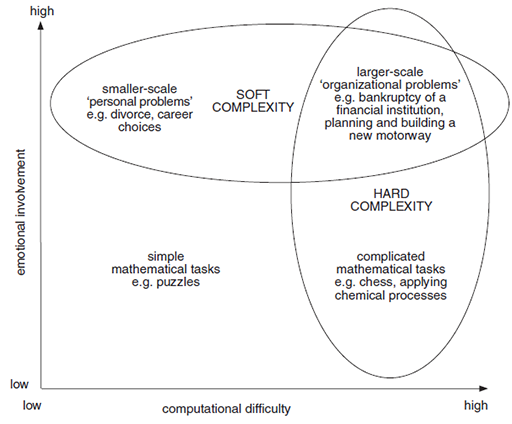

He also argues that the meaning we give to the term complex is dependent on the context. Complexity is not just a matter of there being many different factors and interactions to bear in mind, of uncertainty concerning some of them, of a multitude of combinations and permutations of possible decisions and events to allow for, evaluate and select. It is not only a technical or computational matter, such as what engineers and operational researchers deal with. Complexity is also generated by the very different constructions that can be placed on those factors, decisions and events. Complexity arises from the different perspectives within which they can be interpreted and the degree of emotional involvement people have in the situation. This is so important, and in my experience, so difficult to come to terms with - especially if you have a technical or engineering background - that it is worth discussing further.

It will help to put a label on these different aspects of perceived complexity. The first aspect, which I have referred to as generating difficult computational problems, can be called ‘hard complexity’, and is illustrated by the game of chess. With up to sixteen pieces on each side at any one time and many moves that could be made by each one, the range of possibilities is enormous: a vast number of move and counter-move sequences may have to be considered and assessed. It is, unquestionably, complicated. Nevertheless, the nature of the game, the moves of the pieces, the fundamental purposes of the players – all these are unproblematic.

By contrast consider the situation in a detective story at the end of the penultimate chapter when the detective is about to unravel the mystery. Once again, the situation is complicated, but in a quite different way. Usually the number of possible murderers is quite limited - perhaps only half a dozen. So on the face of it, choosing among them should be a fairly manageable task. But in this case the complexity arises not from the ‘facts’, but from the variety of quite different constructions that can be put on them. Such information as the author has given you may in principle be sufficient but it is seriously incomplete, and also contains much that will prove quite irrelevant or misleading. To solve the problem you have to recognise the significance of chance remarks and relate these to alternative explanations for behaviour or events. And very little can be taken for granted: it may not even have been a murder, but a suicide designed to incriminate someone else, or a case of a corpse disguised and disfigured to look like the person who has escaped with the loot to Paraguay and so on. Each reader will, before the final unravelling, have different hunches about who did what, how and why. The description of events is ambiguous, and deliberately so, while the reader’s degree of emotional involvement can also be high. Complexity of this sort can be called ‘soft complexity’. Figure 4 illustrates the distinctions and similarities of hard and soft complexity.