5 From methodologies to tools

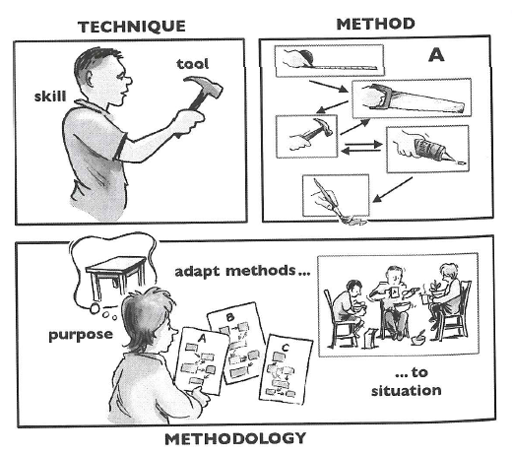

As you engage with systems thinking and practice you will become aware how different authors refer to systems methodologies, methods, techniques, and tools, as well as systems approaches and associated skill sets. Having just spent some time explaining what I mean by a systems approach, I now want to distinguish between methodology and method, and also tools, techniques and skills.

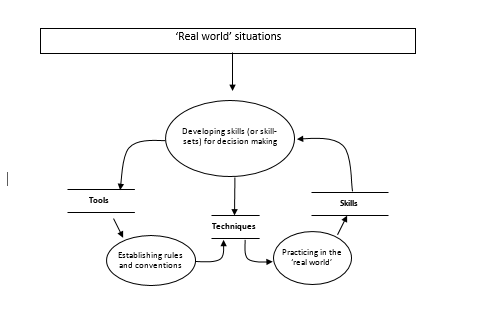

Within systems practice, a tool is usually something abstract, such as a diagram, used in carrying out a pursuit, effecting a purpose, or facilitating an activity. Technique is concerned with both the skill and ability of doing or achieving something and the manner of its execution, such as drawing a diagram in a prescribed manner and also applying it to a given situation. An example of technique in this sense might be drawing a flow diagram to a specified set of conventions. This can be exemplified by Figure 5, developed by The Open University’s Martin Reynolds, which uses a tool, a flow diagram. He uses the associated set of rules and conventions for flow diagrams: arrows to represent information transfer; open-ended boxes to represent transient information stores; closed boxes to represent either sources or destinations of information; and oval shapes to represent associated activities. It is up to you to decide if the use of this technique is appropriate for conveying the difference between tools, techniques and skills.

A similar set of distinctions as shown in Figure 5 might be made but at a different level of recursion for methods, approaches and methodologies. Methods are an elaboration of codified use of tools as ‘techniques’. An approach is more associated with a set of theories/assumptions that have informed the development of the methods associated with any one approach. The key thing though is that the methods are not ‘locked’ in to the paradigm of an approach; they are tools that can be used outside of any prescribed paradigmatic use.

Equally, several authors and practitioners have emphasised the significance of the term ‘methodologies’ rather than methods in relation to systems. Within the frameworks espoused here a method is used as a given, much like following a recipe in a recipe book whereas a methodology can be adapted by a particular user in a participatory situation. There is a danger in treating methodologies as reified entities – things in the world – rather than as a practice that arises from what is done in a given situation. A methodology in these terms is both the result of, and the process of, inquiry where neither theory nor practice take precedence (Checkland, 1985).

When speaking of SSM, Peter Checkland claims:

One feature never in doubt was the fact that SSM is methodology (the logos of method, the principles of method) rather than technique or method. This means that it will never be independent of the user of it, as is technique.

For me, a methodology involves the conscious braiding of theory and practice in a given context (Ison and Russell, 2000). An aware systems practitioner, aware of a range of systems distinctions (concepts) and having a toolbox of techniques at their disposal (e.g. drawing a systems map) as well as systems methods designed by others, is able to judge what is appropriate for a given context in terms of managing a process. This depends, of course, to a large extent on the nature of the role the systems practitioner is invited to play, or chooses to play. When braiding theory with practice, there are always judgements being made: ‘Is my action coherent with my theory?’ as well as, ‘Is my experience in this situation adequately dealt with by the theory?’ and, ‘Do I have the skills as a practitioner to contribute in this situation?’ There are also emotional feelings – ‘Does it feel right?’

There is nothing wrong with learning a method and putting it into practice. How it is put into practice will, however, determine whether an observer could describe it as methodology or method. If a practitioner engages with a method and follows it, recipe-like, regardless of the situation then it remains method. If the method is not regarded as a formula but as ‘guidelines to process’, and the practitioner takes responsibility for learning from the process, it can become methodology.