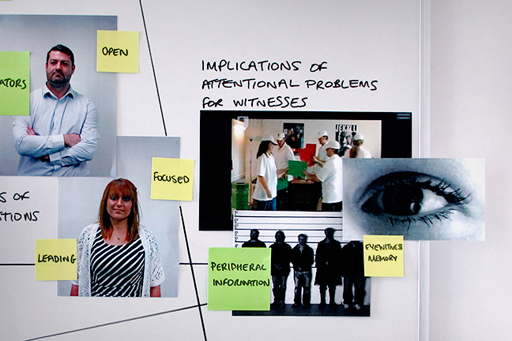

2.2 Implications of attentional problems for witnesses

Both inattentional and change blindness have important implications for eyewitness memory. Even if you spotted the giant mouse in the video, do you think you could attend to all aspects of a crime?

You have seen that there are limits to our attentional capacity so it would not be surprising if, especially with a criminal event, our attention is directed towards particular aspects of the crime at the expense of others, thus influencing what is later remembered.

Migueles and García-Bajos (1999) found that when participants watched a film depicting a kidnapping attempt, actions were remembered better than details. The film contained both central information (the kidnapping itself, which happened suddenly and quickly and involved a young woman being forced into a van), and peripheral information (incidents that were not key to the actual kidnapping, such as a boat arriving at a busy port and passengers getting off). Some of the central and peripheral information was classified as describing actions (for example, that a man lifted up the tarpaulin of the van or that a young man who tried to help the girl struggled with the kidnappers) and some was classified as details (for example, that the name of the boat was Samaina or that the hand of one of the kidnappers was bandaged).

Migueles and García-Bajos found that participants viewing the film later reported equal amounts of central and peripheral information overall. However, whereas the peripheral information included similar amounts of actions and details, the central information retrieved contained more actions than details. Such findings suggest that when witnessing a crime our attention may be drawn to central actions at the expense of descriptive details, although in other circumstances our attention may be spread more evenly between actions and details.

Inattentional blindness operates because our attention is drawn towards just one aspect of the environment that we can see in front of us, resulting in us not noticing other things. When witnessing a violent criminal event, a phenomenon referred to as ‘weapon focus’ has been observed, where the use of a weapon – a gun or knife, for example – attracts the attention of witnesses at the expense of their attention to other details, such as the perpetrator’s facial and physical characteristics. After the event, a witness’s memory of these other details is impaired.

This phenomenon is supported by data from a number of experiments using different procedures. For example, in a laboratory experiment, Cutler et al. (1987) showed videos of robberies to participants. In half of these, the robber openly wielded a handgun, whereas in the other half he hid the gun in his jacket. When asked to identify the robber in a line-up, 46% of participants who viewed the videos where the gun was concealed made correct identifications. However, just 26% of participants who saw the gun made correct identifications. One explanation for this difference is that the participants who saw the gun tended to focus on it to the exclusion of other details, including the facial appearance of the perpetrator.

In a study by Maass and Kohnken (1989), participants were approached by an experimenter displaying either a syringe or a pen. Later recognition showed the experimenter’s face was falsely identified in a line-up by 65.9% those participants faced with the syringe compared to only 45.2% of participants faced with the pen. Again, it is likely that the attention of participants in the syringe condition was drawn to the syringe, meaning they did not attend to the facial appearance of the experimenter.