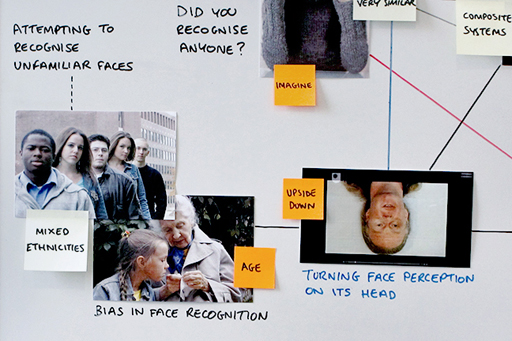

3.4 Bias in face recognition

Our ability to recognise faces is highly developed and different to most other objects. The existence of prosopagnosia and the fact that showing faces upside down affects their recognition more than it does other objects, is evidence of that.

Moreover, it seems that we develop skills to recognise the types of faces we come in regular contact with, which is why it is so hard to recognise an upside-down face.

One implication of this is that our face recognition processes are biased towards the faces we see from day to day. That means that these same processes are not so good when it comes to faces that we are not so familiar with. For example, research such as Harrison and Hole’s (2009) has shown that we tend to be better at recognising faces from our own age group, or from age groups that we are in regular contact with. In other words, our face recognition skills are biased towards those faces we regularly come into contact with (this explanation is known as the ‘contact hypothesis’).

The contact hypothesis can also explain why there is a tendency for us to be better at recognising faces from our own race/ethnicity. For example, a large-scale analysis of available studies conducted by Meissner and Brigham (2001) found that own-race faces were 1.4 times more likely to be recognised than faces from another race. In addition, and of particular relevance to eyewitness identification, own-race faces were 1.6 times less likely to be mistakenly identified than faces from a different race.

The amount of contact that someone has with another race will tend to improve their ability to recognise faces from that race, but own-race bias is still a significant problem in countries that have a population of mixed ethnicities, such as the UK and USA. The research certainly suggests, for example, that Caucasian witnesses in the UK and USA will tend to be much more accurate when it comes to recognising white suspects compared to black suspects – and also more likely to incorrectly identify an innocent black suspect.

You have seen that faces are recognised using different cognitive processes than other objects, and heard from someone unable to recognise the faces of even her close family.

Our face-recognition skills are highly developed and cope very well with the everyday demands of recognising people we are familiar with and with analysing expression and emotion. However, the cognitive processes that are very good in most everyday situations may let us down in unusual circumstances. This includes attempting to recognise unfamiliar faces seen only briefly and faces that we do not have a lot of contact with – including faces of other age groups and ethnicities other than our own.