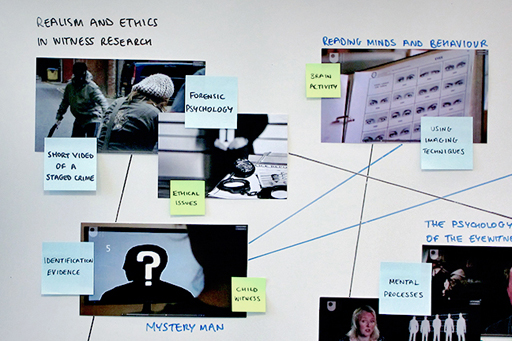

1.5 Issues of realism and ethics in witness research

Research carried out in forensic psychology has not gone without criticism. In particular, research that has involved simulations in the laboratory has been questioned on the grounds of its ecological validity – in other words, how true to life it is.

For example, because the law restricts access to real jurors for research purposes, the jury decision-making process has been studied in many cases by asking psychology undergraduates to read a fairly short written description of a criminal case and to make decisions about the guilt/innocence of the defendant.

As you have seen, the identification of perpetrators has been studied by showing participants a short video of a staged crime scenario and then later asking them to select a picture of the perpetrator from an array of photographs. Psychologists themselves have debated the practical utility of the findings of such studies. Researchers have responded to criticisms by supplementing these rather basic simulations with much more sophisticated ones that have greater ecological validity, and by interviewing real witnesses to crimes and real jurors after they have served in a court case.

The use of ‘field studies’ also helps combat the problems associated with ecological validity. For example, rather than show a video and photographs in a laboratory setting, an eyewitness researcher might stage a ‘live’ crime in front of participants and then conduct an identification procedure at a police station.

In addition to ecological validity, eyewitness research may lack realism in that it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to replicate the seriousness of the decisions faced by a real eyewitness. This is known as ‘consequentiality’, which refers to the fact that unlike a real witness, a participant in a research study knows that the information they provide or the face they select in a parade will not result in either an innocent person being prosecuted nor a guilty person walking free.

Ethical issues are paramount when conducting any psychological research, and particularly important when dealing with an issue as particularly sensitive as witnessing a crime. By its very nature the experience of crime is often frightening and may be painful and researchers face severe limits on the extent to which they can mimic such aspects when conducting a study.

There are a great many ethical factors to consider when planning research on eyewitnesses, including:

- research should not threaten the psychological well-being, health, values or dignity of participants

- participants should give informed consent before taking part in research

- participants should be able to stop participating in the research at any point.

Ethical issues require careful consideration when designing a research study, particularly with regards to how realistic the research can be.

The requirement to gain ‘informed consent’ from a participant before they take part in the research, means the participant must be provided with details regarding what the research involves and what will happen to them. In real life, a witness does not know they are about to see a crime, but in a research study the participant must be informed in advance.

So, research on eyewitness memory has to balance ecological validity with the need to treat participants ethically. Designing research studies that are both ethical and sufficiently realistic that they produce useful results is just one of the skills the psychologists have to learn.