2.1 Looking for water from lunar orbit

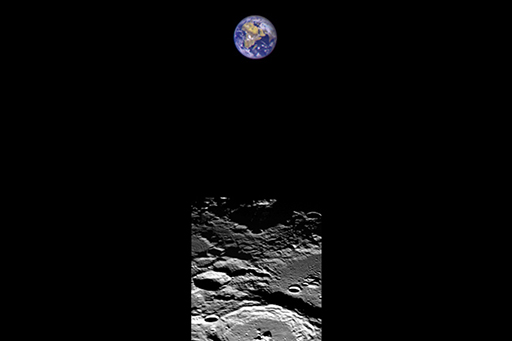

After a hiatus in lunar exploration of two decades from the last Apollo mission in 1972, in 1994 NASA’s Clementine spacecraft was sent into orbit around the Moon with a mission to map the chemical and mineral composition of the lunar surface.

Using its on-board instruments, a mid-mission decision was made to conduct what was called the Bistatic Radar Experiment. For this experiment, the spacecraft used its radio transmitter to bounce radio waves off the surface of the Moon, bombarding the surface near the north and south lunar poles. The reflected radio waves were picked up by a powerful Deep Space Network (DSN) radio antenna back on Earth.

By looking at the scattering patterns of the radio waves, scientists were able to tell what sort of material the signals were being reflected off. This led them to an exciting conclusion, which was published in 1996; it seemed that the floors of some of the craters near the Moon’s poles were coated in water-ice. Because the Moon’s axial tilt is so slight, there are some deep craters near to the lunar poles that never see sunlight, and so are extremely cold. In fact they are cold enough for any water inside them to remain stable as ice over millions or even billions of years.