3.2 TAPCHAN and other fixed devices

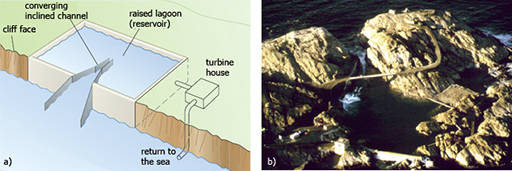

The TAPCHAN (‘TAPered CHANnel’) concept is simple. The first, and so far only, example was built on a small Norwegian island. It has a channel with a 40 metre wide horn-shaped collector. Waves entering the collector were fed into the wide end of the tapered, upward sloping channel, where they then propagated towards the narrow end with increasing wave height.

The kinetic energy in the waves was thus converted into potential energy, and this was subsequently converted into electricity by allowing the water in the reservoir to return to the sea via a low-head Kaplan turbine system. This powered a 350 kW generator that delivered electricity into the Norwegian grid.

With very few moving parts, The TAPCHAN’s maintenance costs should be low and its reliability high. The storage reservoir also helps to smooth the electrical output.

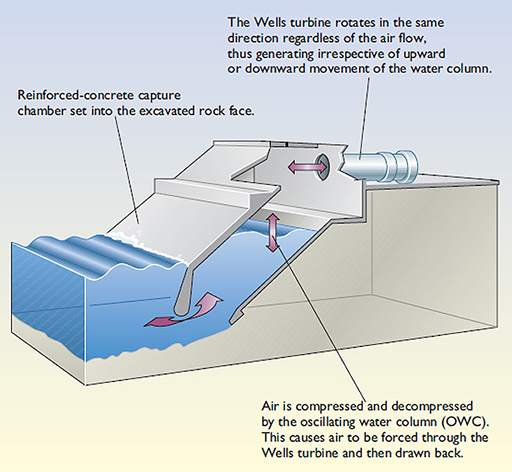

Fixed OWC devices have been investigated in a number of locations, with slight variations to the basic concept.

In the mid-1980s Queen’s University, Belfast (QUB) worked on the development of a shoreline oscillating water column (OWC) device on the island of Islay in Scotland. It supplied the local grid with electricity on an intermittent basis from a 75 kW generator from 1991 until it was decommissioned in 1999. The QUB approach was to develop a device that could be built cheaply on islands using locally available technology and plant.

To overcome some of the limitations of its first prototype, the QUB team went on to develop a second design called LIMPET (Land Installed Marine Powered Energy Transformer).

The ‘designer gully’ where it was installed was excavated in order to improve the flow of water into and out of the oscillating chamber, and the main part of the gully chamber was built at a slope so as to efficiently change the water motion from horizontal to vertical and vice versa (Figure 15).

Construction of LIMPET was completed in September 2000. It has a 500 kW maximum power output, has accumulated many thousands of hours of operation in more than ten years, and is used as a test bed for air turbines.

Other, non-OWC fixed device prototypes have also been tested in Japan and Scotland. A number have used a mechanical linkage between a moving component, such as a hinged flap, and the fixed part of the device. In Scotland, a device called Oyster, capable of delivering 315kW was installed at the European Marine Energy Centre in 2009. A second generation Oyster, capable of delivering 800 kW, was commissioned in 2012. Unfortunately, after an investment of £3 million, the project was abandoned in 2015.

You’ll look at floating devices in the next section.