1.1 UK electricity scenarios

In 2011 the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), published Positive Energy (WWF, 2011a), describing a range of UK electricity scenarios for 2030 based on detailed analysis by the specialist consultancy Germanischer Lloyd Garrad Hassan (GLGH). The report demonstrated that renewables could contribute some 60–80% of the UK’s electricity by 2030. GLGH created six scenarios for the UK electricity sector in 2030, with the first three ‘Central’ scenarios assuming only modest attempts to reduce UK electricity demand, whereas the second three involve more ambitious energy conservation measures.

The report comments:

In all cases, the scenarios make full provision for ambitious increases in electric vehicles (EVs) and electric heating. Energy efficiency and behavioral change lead to the reductions in demand in the ambitious demand scenarios.

The volume of renewable capacity installed by 2020 in all scenarios is similar to that set out in the government’s Renewable Energy Roadmap in July 2011. However, critically, the scenarios envisage installation continuing at a similar rate during the 2020s. This will avoid the risk of ‘boom and bust’ in the UK renewables sector [...] and mean renewables provide at least 60% of the UK’s electricity by 2030.

The amount of renewable capacity the UK can and should build is determined by economic constraints – not available resources or how fast infrastructure can be built. GLGH assumes that it is economic to supply around 60% of demand from renewables. Going beyond 60% depends on whether there’s a market in other countries for the excess electricity the UK would generate at times of high renewable energy production.

An even more ambitious scenario, envisaging the UK making a transition to a ‘Zero Carbon Britain’ (ZCB) powered entirely by renewables by 2030, was published by the environmental charity the Centre for Alternative Technology (CAT) in 2013 and 2018. This transition would be achieved through ‘Powering Down’ – reducing energy demand without reducing quality of life; and ‘Powering Up’ – deploying renewable energy on a large scale and very fast. (Zero Carbon Britain, 2018).

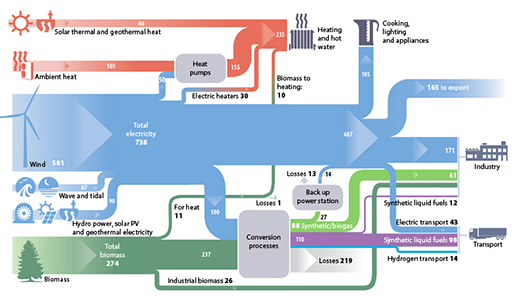

Figure 1 summarises how the ZCB scenario envisages energy flowing in 2030 from a variety of renewable energy sources, via various energy conversion processes, to supplying energy for heating, cooking, lighting & appliances, industry and transport.

The ZCB scenario is based on a detailed hourly model of UK energy supply and demand. In it, the majority of renewable electricity comes from a very large capacity of on-shore and offshore wind power, and there will be many occasions when this supply exceeds electricity demand. The ZCB researchers propose a ‘power to gas’ process in which surplus renewable electricity is converted into hydrogen by electrolysis. This is then combined with carbon dioxide from biomass to produce methane, which can be distributed and stored in the existing UK gas grid and burned in the UK’s conventional backup power stations (which normally burn fossil methane) when there is a deficit of renewable electricity.

In addition, some of the hydrogen and carbon dioxide are instead converted to a synthetic liquid fuel, methanol, which can be used as a substitute for gasoline in many vehicles.

Watch the following video, which gives more information on the thinking behind the ZCB scenario.

Transcript

These proposals are extremely radical and ambitious, but the UK’s offshore renewable energy resource, from wind, wave and tidal sources, is huge. In 2010 the Offshore Valuation study (Offshore Valuation Group, 2010), backed by the Crown Estate, UK and Scottish government departments and some major companies, concluded that it is equivalent in size to the UK’s offshore oil and gas resources – but unlike these fossil resources, the renewable resources do not suffer from depletion and should be available for an indefinite period.

The study also showed that the majority of the wind resource is located far offshore, and could be harnessed using floating turbines moored in very deep waters. As shown in Week 6, a number of companies including the Norwegian company Statoil are developing floating wind turbines.

But what’s involved in balancing supply and demand? You’ll look at that in the next section.