4 Renewable energy futures for Denmark

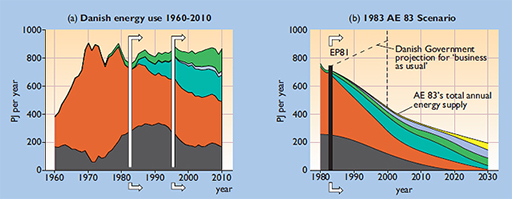

Denmark is a good example of a country that started promoting renewable energy back in the 1980s. During the 1960s, Denmark’s energy use expanded rapidly in an era of cheap oil (see Figure 3). By 1972 it had become almost totally reliant on imported oil and was badly hit by the ten-fold oil price rises in 1973 and 1979.

The situation encouraged energy researchers from Danish universities to produce in 1983 an ‘alternative energy scenario’ (AE83). This outlined a programme aimed at cutting oil and coal imports to zero by 2030, to be achieved by an increase in the proportion of renewables (wind, solar and biofuels) and sharply reducting total energy demand. The plan did not include nuclear power, which was unpopular in Denmark at the time.

The AE83 projection, shown on the right of Figure 3b above, is in strong contrast with the official 1981 Danish government ‘Business as usual’ projection EP81 (shown in the dotted line in Figure 4b, which suggested a continued growth in energy demand.

In practice, the Danish government solved its immediate energy security problems in several ways:

- It pursued a policy of energy conservation, imposing high energy taxes and new regulations to encourage the insulation of buildings and promote the use of Combined Heat and Power (CHP). The results were impressive. Between 1972 and 1985, the total heated building floor area increased by 30%, but the amount of energy used to heat it decreased by 30% (Dal and Jensen, 2000).

- It switched power stations from oil-firing to coal-firing. National reliance on oil dropped from 93% in 1972 to only 43% in 1992. It developed its own oil and gas resources in the North Sea. The results started to appear in the early 1980s and by 1997 Denmark had become a net energy exporter.

- It made considerable efforts to start building up its renewable resources, particularly biomass and wind power. Denmark is now a major exporter of wind turbines, technology and know-how.

Actual Danish energy consumption up to 2015 has not followed either the AE83 projection or the government EP81 projection -- which confirms that scenarios are only pictures of what could happen rather than what will happen.

By the mid-1990s, the focus of energy policy had shifted from self sufficiency to climate change. Denmark is a low-lying country and any future sea level rises would have serious consequences. The switch from oil to coal and natural gas meant that national CO2 emissions had remained at their 1970s level.

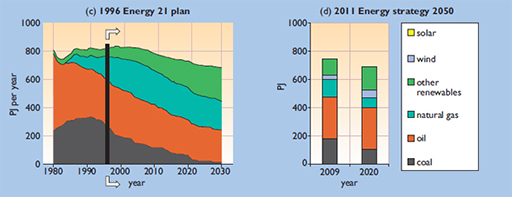

In 1996, the centre-left government adopted a policy of cutting emissions by 20% from their 1988 levels by 2005 and by 50% by 2030, as set out in their Energy 21 plan (MEE, 1996). In this scenario, total primary energy use would fall only slightly and the use of coal would be replaced by increased use of natural gas and renewable energy, as shown at the bottom left of Figure 8.3. It was suggested that by 2030 half of Denmark’s electricity could come from renewable sources.

To implement this policy there were continued high energy taxes and support for renewable energy through a Feed in Tariff (FIT) scheme.

However, in 2001, a new right-wing government was elected which was committed to tax reform. It took the attitude that the country’s environmental initiative was ‘ahead of schedule’, resulting in the Energy 21 plan being dropped, orders for three offshore wind farms cancelled and many tax incentives for energy efficiency scrapped.

In May 2011, the Danish government produced a new ‘Energy Strategy 2050’ stating a long-term goal of a complete transition away from the use of fossil fuels by that date (Danish Government, 2011), as shown on the right of Figure 4. This is essentially the same goal as the 1983 AE83 scenario but with the target date delayed by 20 years. It involves:

- a continuing reduction in overall energy demand

- a reduction in the use of coal in electricity generation, to be replaced by renewables

- a continued expansion of the use of renewable energy, particularly solid biomass and wind power.

In 2010 renewables supplied 33% of the country’s electricity, nearly 21% from wind power.

There is an intermediate target that renewables will contribute over 30% of final (delivered) energy use by 2020 (around 200 PJ per year), with a 10% contribution to the transport sector. In the electricity sector it is suggested that 60% should come from renewables, 40% being from wind power.

A comparison of projected 2020 energy use with that of 2009 is shown on the right of Figure 8.4. This scenario is more ambitious in terms of renewable energy deployment and less reliant on natural gas than the now ‘abandoned’ Energy 21 Plan.

Looking much further ahead, Denmark’s Climate Change Committee (2011) sees the country’s energy future as 100% renewable powered by 2050, from a mixture of onshore and offshore wind, solar PV and thermal panels, biomass fuels (some imported), electric heat pumps, geothermal energy, CHP plants and large heat stores. International electricity links also enable Denmark to export and import electricity when there are surpluses or deficits. This vision has been backed up by an earlier study from the Danish Society of Engineers (2010).

What are Germany’s renewable energy plans? You’ll discover in the next section.