2.7 Habitable places

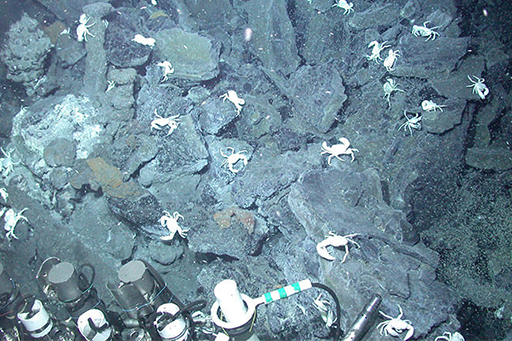

Volcanoes can be a source of devastation but they can also give nutrients and heat. At mid-ocean ridges on the Earth, life takes great advantage of the warm water around volcanic vents and especially of the hot water vents where nutrients leave the volcanic system. A special food chain evolves there, with microbes taking advantage of the chemical energy supplied by the vents. Minerals formed from the precipitation of the hot volcanic waters can be the source of energy for some of the microbes, too. The microbes form the basis of the food chain. More complex life forms harvest the simpler life forms as food. The fact that there is no sunlight makes for the white skin of many of the animals. As a consequence, a diverse community of life forms develops around volcanic vents in the great depths of the terrestrial oceans. The number of known species increases with each research dive. Tube worms, spider crabs with diameters up to 80 cm and octopuses have been found. One might speculate that similar ecosystems could develop elsewhere in the Solar System.

Like volcanoes, impact craters are a two-edged sword where life is concerned. To witness a large impact would be a lethal experience because the impactor deposits a huge amount of energy in the target site, causing an explosion. Close to the centre of the impact, rocks become molten and vaporised, and a large depression is excavated. Further away from the site, pressure waves rush over the surface causing any loose material to fly and crash into anything in its path.

But after the dust has settled, the remaining energy, now turned into heat, can create a sweet spot for life, especially in cold and otherwise hostile environments. The depression may become a lake. If there is no rain, underground water may accumulate in the crater. Heat that caused the melting of rocks will take hundreds of thousands of years to dissipate.

The Chicxulub impact crater on Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula is associated with the impact that led to the demise of the dinosaurs. Chicxulub’s 180 km diameter crater will have taken close to 200 000 years to cool below 90 °C. This means that an impact in a frozen world will melt the water and make liquid water available to thousands and thousands of generations of microbes. It makes a habitat that endures for an immensely long time – in relation to the lifespan of a microbe.