6 Can citizens contribute to science?

Scientists study and propose hypotheses, exploring the natural world around us by way of scientific enquiry. When applied to learning, an enquiry-based approach can help learners to develop their own knowledge, coming to understand scientific ideas and the process of investigation. Citizen science can provide a way for people to learn about science through participation in authentic scientific research: observing and monitoring species, collecting data, tackling environmental issues, etc.

One way of seeing how citizen science can contribute to scientific research is by looking at how initiatives are designed to meet science-based objectives. It has been suggested that an important consideration for those involved in citizen science is whether it is the best approach for the research question. If it is, projects should be driven by a research question (hypothesis) or monitoring agenda that fits within a specific science or conservation mission, considering also the participants’ skills levels in order to determine the need for additional training or other support needed. Second, it’s important for a research team to include a professional scientist for any project to have scientific validity and, perhaps, to provide support for the non-professional participants and to communicate the project’s findings. Statistical and technical expertise for data analysis and evaluation can be useful for setting and reporting on measurable objectives.

The design of data-collection methods is another step towards developing, testing and refining data forms and other resources. Recruiting and training participants is also important and should be approached with the project goals in mind, in a way that can facilitate analysis for interpreting and drawing conclusions. Disseminating conclusions and results, ensuring that the data are useful and accessible to a wide audience, is crucial.

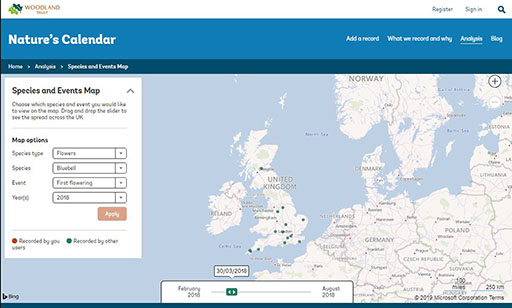

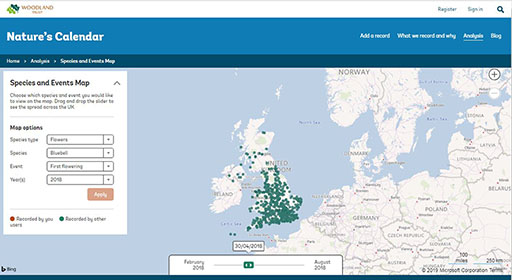

Nature’s Calendar [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] is a citizen science project run by the Woodland Trust and the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. Members of the public are invited to contribute their records of plant and animal annual events e.g. leaf buds bursting, blackberries ripening or the arrival and departure of migratory birds. This populates a database through time and space of these phenological events – the seasonal changes observed in wildlife each year (see Figures 10 and 11). Since these are often determined by meteorological conditions, such as temperature, scientists can use this database to investigate the effects of weather and climate on wildlife.

Citizen scientists select a subject in an area which they visit regularly, (e.g. an oak tree near where they work or butterflies in their garden), and monitor it several times a week for a significant event (e.g. bud burst or first sighting). Participants can then upload their observation to the website, where they can see a map and a time slider showing how the event develops through the months across the country. As participants enter a new record for the same spot every year, they can see whether this has happened earlier or later than in previous years, and compare this with other people’s observations throughout the rest of the country.

It would be impossible for a researcher to record the timing of a wildlife event over such a large geographical area, even if they were able to make accurate predictions about when it might happen. However, when citizen scientists can use a simple guide for identifying species and their associated events they are able to provide a large quantity of good quality data. Nature’s Calendar has been set up to include common and easily recognisable species that already have an existing historical record, in order to make their records comparable and consistent. Citizen scientists are contributing to this database which already contains over 2.7 million records and can be compared with previous records dating as far back as 1736.

Activity 3 Colecting data in Nature’s Calendar

Scientists have used the data collected by the public in Nature’s Calendar to assess how these phenological events have been changing. Their results are suggesting that spring events are coming earlier while autumn events are getting later. This can be linked to rising temperature providing a longer growing season. By covering many different groups of species- amphibians, birds, fungi, insects and plants, researchers are also able to understand how the interactions and interdependencies between these species could change in the future. Changing phenology provides the first indication of how a species is responding to long-term climatic changes, and can help researchers establish which species will suffer and which will benefit under new conditions. These results have been published in scientific journals and shared with the public in articles.

Questions to consider (you can write your response in the box below):

- What kind of data is being recorded?

- How were the public engaged and involved?

- How was data collected?

- Why are citizen scientists so important?

- What are some of the conclusions or results?

- How was this shared or disseminated?