5 The physiology of overtraining

Exercise physiologists are interested in the functions and mechanisms of the human body’s response to exercise.

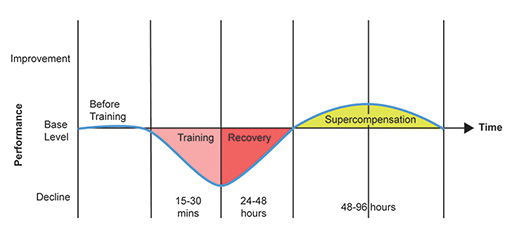

Figure 6 illustrates the concept of supercompensation (the process of the body adapting to the progressive demands of training). The timescales involved are very broad estimates but do indicate that far longer is needed for recovery and adaptation than some people realise. This is why training plans often aim to stress different muscle groups at different times in a training period and why consistently high training volumes and intensities make it more difficult to sufficiently recover between sessions.

Ideally, athletes follow a periodised programme which varies the volume, intensity and training focus: this enables supercompensation and recovery but minimises fatigue.

Leading strength and conditioning coach Vern Gambetta (2007) explains:

The body is always seeking to maintain a state of homeostasis [equilibrium] so it will constantly adapt to the stress from its environment … the desired adaptive response is called supercompensation. … The first step is the application of a training stress and the body’s subsequent reaction to this …: fatigue or tiring. There is a predictable drop-off in performance because of that stress. Step 2 is the recovery phase. … As a result of the recovery period, the energy stores and performance will return to the baseline (state of homeostasis) … Step 3 is the supercompensation phase. This is the adaptive rebound above the [performance] baseline; it is described as a rebound response because the body is essentially rebounding from the low point of greatest fatigue. This supercompensation effect is a physiological, psychological and technical response.

The penultimate word ‘technical’ refers to improvements in skills, techniques and accuracy in a movement. You will now consider what happens when repeated training sessions apply training stress. Here, a new term will be introduced: overreaching.