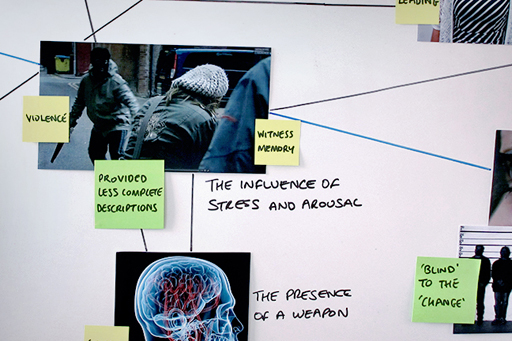

2.4 The influence of stress and arousal

The relationship between violence, arousal and witness memory is by no means clear-cut. In real crimes, the presence of a weapon is likely to be confounded with a higher degree of threat of violence and therefore of stress-induced arousal. One study involving analysis of police records showed that victims of violent crimes, such as rape or assault, provided less complete descriptions of the perpetrator compared to victims of less violent crimes (Kuehn, 1974).

The influence of violence on memory could be explained in terms of emotional arousal or stress. Increased violence may result in higher levels of stress, which may then impact negatively on memory. It has been suggested that memory performance may follow the Yerkes–Dodson Law, long established in psychology (Yerkes and Dodson, 1908), which suggests that although a small to moderate amount of stress may improve performance, a large amount will have a markedly negative impact.

Other evidence casts doubt on such a simple relationship between arousal and eyewitness memory. For example in a robbery in Canada, a thief entered a gun shop, tied up the owner and took money and guns. The owner freed himself, collected a revolver and left the shop to get the licence number of the thief’s car. This led to a confrontation: standing six feet away, the thief fired two shots at the owner, then the owner discharged six shots, killing the thief. The owner survived severe injury. Of the 21 witnesses who saw the event, 15 were interviewed on the same day and the remaining six within two days. A detailed description of the incident was constructed from their accounts, forensic evidence, and photographs, etc., so that witness accuracy could be calculated.

Yuille and Cutshall (1986) reported high levels of accuracy in the reporting of this traumatic event by witnesses. With the exception of one witness, all reported event-related stress, but for some this appeared about half an hour after the incident; during the incident itself they were only aware of ‘adrenalin effects’. Adrenalin is a hormone that is released in stressful situations and heightens the heart rate. The five witnesses who had contact with either the thief, store owner or weapon reported the greatest amount of stress. They showed a mean accuracy of 93% compared with 75% for the remaining witnesses. As these five witnesses were also closer to the event, arousal level and proximity were confounded in this case.

Christianson and Hubinette (1993) conducted a wide-scale study involving witnesses to 22 bank robberies. They found no significant relationship between rated degree of emotion and the number of details remembered, and therefore no evidence that high arousal will impact on memory. They approached 110 witnesses, of whom 58 were willing to participate in the study, and of these 20 were victims (bank tellers), 25 fellow employees and 13 customers. The witnesses were interviewed and studied with respect to emotional reactions and memory for detailed information about the robbery. Their accounts were then compared with that initially recorded in police reports.

The findings revealed relatively high accuracy rates after an extended time interval (4–15 months) with respect to specific details about the robbery, namely actions, weapon, clothing etc. However, witnesses showed rather poor memory for certain items: footwear, eye colour and hair colour. Findings also revealed that the victims had higher accuracy rates than the bystander witnesses in relation to the circumstances surrounding the robbery (information about date, day, time and number of customers), but this was not related to differential emotional experiences as victims did not report being more emotionally aroused than bystanders. As a whole the results indicate that the specific details directly associated with a highly emotional real-life event are well retained over time.

The results of the study by Migueles and García-Bajos (1999) suggest that when witnessing a crime, our attention may be drawn to the central actions at the expense of descriptive details. Generally, studies investigating the effect of emotional arousal on memory have revealed a fairly consistent pattern. Participants’ memory for certain central, critical details of emotional or violent events tends to be accurate and persistent over time but their memory for peripheral, irrelevant details or surrounding/circumstantial information tends to be less accurate. Easterbrook (1959) suggested that arousal may narrow the focus of attention so that memory for central details will improve, at the cost of memory for peripheral details. The notion of attention narrowing has been used to explain the phenomenon of ‘weapon focus’.