1.2 Fair line-ups

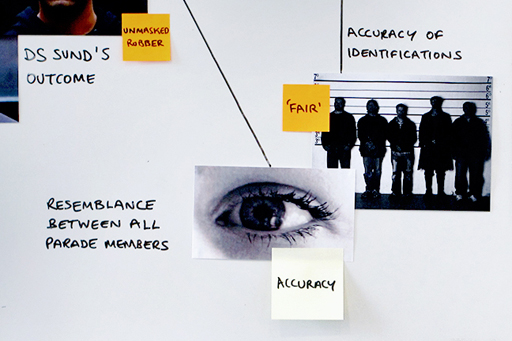

The structure of the line-up must be ‘fair’ so that there is a reasonable degree of resemblance between all parade members.

This is the third, and perhaps most important, factor in the accuracy of eyewitness identification. It should hopefully be obvious that if a parade contains a dark-haired black female suspect and eight blonde white male foils then it would be a very unfair parade indeed! Although such a parade would not be deemed acceptable, it demonstrates that there is a difference between the number of people in a parade and the number of people in a parade that resemble the suspect – and research has shown that it is very common for parades to contain people that do not resemble the suspect.

One difficulty here is whether the foils in the line-up should be chosen to resemble the suspect (the procedure used in England or Wales), or whether they should match the general description of the culprit as provided by the witness. Some have argued that to select the foils in the line-up on the basis of their similarity to the suspect creates an unnecessary similarity between the foils and the suspect and can make the task too difficult for the eyewitness.

Wright and Davies (1999) provide the following example that highlights this issue.

The witness described the perpetrator as a six-foot tall male with brown curly hair. The police have a suspect who fits this description but who also has a scar on his face, something the witness did not mention. If the police select the foils to match the witness’s description, and the suspect is innocent, the scar should help safeguard the suspect against being picked out, as the witness has no memory of a scar. However, should the suspect be guilty and the witness has failed to mention a scar when providing a description, then this may help the witness correctly identify him as the perpetrator as he is likely to be the only one with a scar (the witness is able to recognise the scar, even though they did not recall it during their interview). An exception is where this results in the suspect ‘standing out’ in some way.

In this example, should the suspect be five feet six inches tall rather than six feet tall, then choosing the foils all to be six footers would make the suspect stand out.

Psychologists assess the fairness of an identity parade by showing it to people who have never seen any of the faces before and asking them to pick the person who is the best match to the description of the perpetrator provided by the witness. If the parade is completely fair, then each member of the parade should be equally likely to be chosen. However, if the parade is unfair, then the suspect will be selected an unequal number of times. Research conducted by Valentine and Heaton (1999) used this technique and estimated that in the ‘live’ line-ups that used to be employed in the UK (prior to 2003) the suspect was selected 25% of the time. If the parades had been completely fair, they should only have been selected 11% of the time. In comparison, when it came to video parades (such as those now used in the UK), the suspect was only chosen 15% of the time, suggesting that they are much fairer than live line-ups. The likely explanation for this is that video parades are constructed from a database of thousands of faces, while live line-ups require an officer to physically find people who look like the suspect.