2 Using reflection to improve performance

The ability to reflect on actions, and how effective they were, is expected of managers and, quite often, of teams. Reflection can even take place at an organisation level, for example, after a major change. Here we deal with individual reflection.

Donald Schön (1983) talks about reflection-on-action which happens after an action. When reflecting on action, you think back on what happened, why it happened, how you dealt with it and whether you could have handled it differently to obtain better outcomes. Reflection-on-action requires critical thinking, involving analysis and evaluation, without the emotional biases that can prevent clear thinking. It means going beyond the surface of things and deconstructing an event or events as rationally as you can.

This might take the form of a cycle in which you consider the action you have taken as well as the consequences, and consider what might have been done differently. In doing so you create knowledge that is new to you and which you can apply in future situations. In the process you learn more about your own thinking which enables you to improve it. For example, you might recognise that you had knowledge that you didn't apply or that you needed more knowledge or information, or that your feelings, personal beliefs or expectations influenced your thinking without you realising it. Thus, the next time you act you are much less likely to repeat past mistakes or oversights.

Kolb’s learning cycle, which you met in Section 1, is an example of this approach to reflection. Pedler et al. (2001) suggest a rather different approach to reflection which takes into account the way emotions, feelings, beliefs and expectations can influence the way we act. These are often implicit, that is, we are often unaware of them. For example, we may feel fearful of a new project, or jealous of another person's good fortune. In the first instance these feelings may stem from a lack of belief in our capabilities, and in the second from an expectation or belief that life is (or should be) fair when the reality is that it is not naturally that way. Thus feelings need exploration to expose the implicit beliefs, expectations and values (and information) that give rise to them.

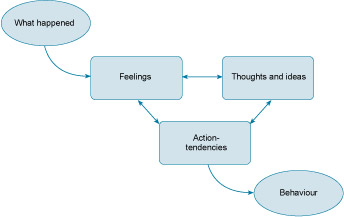

Pedler et al. refer to habitual ways of working (or thinking or behaving) as action-tendencies (Figure 3). These are often easier to recognise in others than they are in ourselves. Consider a person with whom you work closely: in a tense situation, how does that person behave? What is his or her usual response to a request? If it is hard to recognise your own action-tendencies, ask one or two people you trust to give you honest and non-judgemental feedback. However, try not to react negatively to what they say. Action-tendencies are not necessarily problematic or negative, but knowing what yours are can deepen your understanding of your own actions and help you to reflect on them.

In the next sections you will be introduced to self-management and team working skills and as you work through these sections you will be encouraged to reflect on your current practice and to think of ways to improve it. At the end of this course you will return to the question of how you can use reflection to improve your performance.