5 Are you seen as a leader?

Beyond the traits and behaviours they demonstrate, leaders also need to remember that they are being judged and evaluated constantly by those around them – and this can have an impact on their effectiveness as a leader. On a certain level, this might seem to be common sense; after all, leaders of all types have often sought to dress or look the part.

Activity 5 Who do you see as a leader?

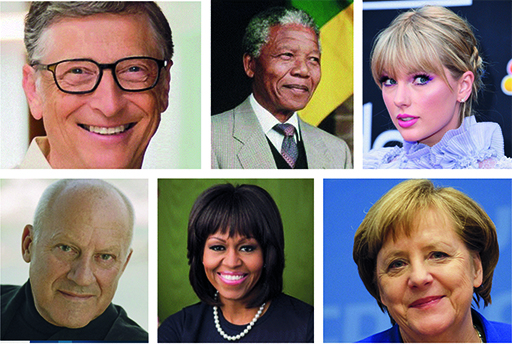

Leadership comes in many guises. Which of the following would you see as a leader, and why?

Discussion

Which of these famous faces did you consider to be a leader? You might wish to compare your responses to a friend, colleague or family member and explore the differences. Understanding not just what those differences are but the reasons for them can be quite revealing.

Recent research in the field of neuroscience has determined how we are judged not just for who we are but for how we are perceived by others. Lyons and O’Mara explain this process as follows.

We make person judgements on the basis of two simple processes. First, a snap judgement of how cold or warm we feel toward the person. Does this person elicit feelings of kindness, affection, admiration? The feeling of cold or warmth that another elicits is intuitively easy to understand – to label someone as ‘very cold’ is to condemn them. It suggests they are devoid of emotions, that they are selfish, and probably untrustworthy in some core respect. Second, a snap judgement of the competence or incompetence of the person. Competence is less intuitively obvious, but refers to the judgement that the person is capable of acting on their wishes and desires – and further, whether they mean us harm or not.

We then combine these judgements quickly. These rapidly-formed composite judgements (Cold/Warmth and Incompetence/Competence) reliably and rapidly elicit particular emotions, and these emotions in turn directly and indirectly drive our behaviour toward the other person.

In this way, leaders are judged in a similar way to brands:

Leaders are judged as both persons and as brands. Being judged as both a person and as a brand has profound implications for how leaders should manage and present themselves within the groups and organizations they lead.

These thoughts from Lyons and O’Mara (2016) are developed from the work of Fiske (2011) who created a model called the ‘Stereotype Content Model of Perception’. In the following activity you will learn more about how this model works in practice.

Activity 6 The Stereotype Content Model of Perception

Watch the animation in Figure 4 which describes the Stereotype Content Model of Perception, based on the work of Fiske (2011).

Transcript: Figure 4 The Stereotype Content Model of Perception (adapted from Fiske, 2011)

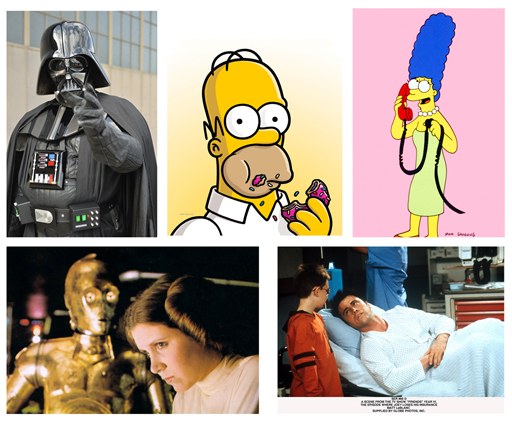

The way we evaluate people on the basis of perceived warmth and competence can apply equally to fictional characters and even brands. Figure 5 shows the images of some well-known fictional characters.

What is your visceral reaction to each of these characters? How might you rate each of them in terms of warmth or competence, as explained in the Stereotype Content Model of Perception?

Discussion

While there is no one right answer – they are fictional characters after all – it might be worth reflecting on how you responded to each. Some typical responses might be as follows:

- Darth Vader – low warmth and high competence

- Homer Simpson – high warmth and low competence, or low warmth and low competence

- Marge Simpson – high warmth and high competence

- Princess Leia – high warmth and high competence or low warmth and high competence

- Joey from Friends – high warmth and low competence.

Curiously, as you have heard, research has found that this model of perception also applies to our engagement with brands. You might wish to think of some well-known brands with which you are familiar – how would you engage with them?

A key lesson – for individuals, for organisations, and for individuals as representatives of organisations – is that, whether we like it or not, people will always develop a perception of us based on an evaluation of their warmth of feelings towards us or their perception of our competence. While we might strive to overcome this, the recognition that this happens on a deep, visceral level is crucial.

Leading neuroscientist Shane O’Mara makes the point that, beyond simply assessing people based on our perception of their relative warmth and competence, this same cognitive process helps us to allocate roles and positions to people within a group. As O’Mara puts it:

Think about the first time you walked in to a group of people that you didn’t know. Quickly, people rank each other as leaders, as followers, as wise voices, as slightly off-beam, along all sorts of dimensions, and we do this rapidly and quickly.

The implications of this for leaders at all levels of an organisation are significant. On the one hand, it is critical that you are aware of both the conscious and subconscious assessments that you are constantly making of others; on the other, you should also be aware of the assessments that others are making of you. In each case, these might or might not be entirely correct – as the old saying ‘Don’t judge a book by its cover’ would suggest – but they happen nonetheless.