Colette Bryce was born in 1970 in Derry, Northern Ireland.

The Troubles were part of everyday life for her, as a child and a teenager. She emigrated to Britain in 1988 and has since lived mainly in London and the north of England.

Bryce describes emigration as a key experience in her adult life: it informs an ‘outsiderness’ in her poetry. Bryce often writes as if she were ‘at one remove’ from the mainstream. You might say this stems from her emigrant perspective, from being called a ‘British’ poet in some places yet ‘Irish’ in others, and from being gay in a predominantly heterosexual culture. Bryce says this is ‘an interesting (no)place to write from’. (quoted in Wyeth, 2020)

Bryce’s poems often look at complex experience by way of a single, clear image. Her writing frequently considers tensions between, for example, borders and crossings, appearance and disappearance, expression and suppression, and public and private life.

Despite the sophistication of her themes, Bryce’s poems are accessible. Her work is also surreal and wry. Famed for her musicality, Bryce often scatters rhymes throughout her poems so they are ‘more heard rather than seen’. She considers poetry to be close to song and is an engaging reader of her own work, as in this video where she reads ‘The Full Indian Rope Trick’ (2005).

The poems of Colette Bryce: between the true and the strange ...

Bryce likes poems that have ‘both clarity and strangeness’, as discussed in an interview with Susan Haigh. You can see this combination in her own work in ‘The Full Indian Rope Trick’.

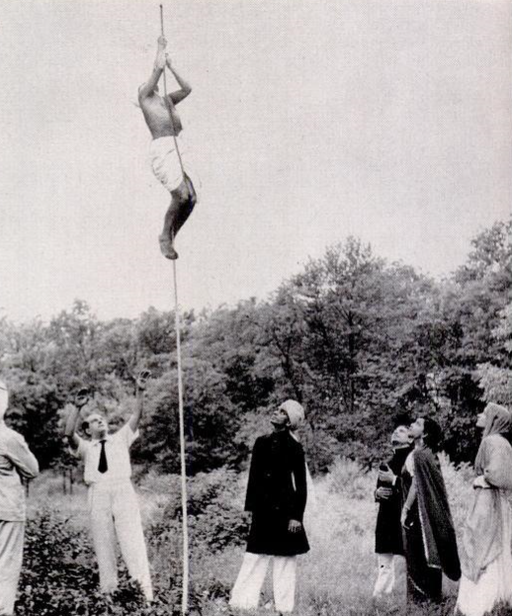

In this poem, she uses the concrete image of a magic trick, but she’s also talking about emigration as a means of escape. The image of the trick is easy to ‘see’, while we learn about the speaker’s ‘painful’ experience of self-determination. The poem is set in a real public space, Guildhall Square in Derry; there are concrete details, ‘walls, bells … a rope’. Notice, however, this ‘one-off trick’ is surreal. The speaker is in two minds: despite climbing to the sky and disappearing, she is ‘still here’ at the poem’s end. In this way, we might say the rope trick stands for a feeling of being ‘there but not there’. And this feeling is typical of emigrant experience.

Bryce discusses this aspect of the poem in an interview with Alex Pryce in Poetry London. ‘The Full Indian Rope Trick’ is characteristically musical. You might like to read it aloud to yourself to catch all those internal rhymes, for example: ‘passers-by’, ‘sky’, ‘goodbye. // Goodbye’, ‘First try’ and ‘eyes’.

The magician Joseph Dunninger with students from Columbia University demonstrating the Indian Rope Trick

The magician Joseph Dunninger with students from Columbia University demonstrating the Indian Rope Trick

... between public and private ...

Having grown up on a political faultline, Colette Bryce is aware of borders, restriction and freedoms. This comes through subtly in her personal poems when she writes about criss-crossing the gap between public ‘norms’ and private life.

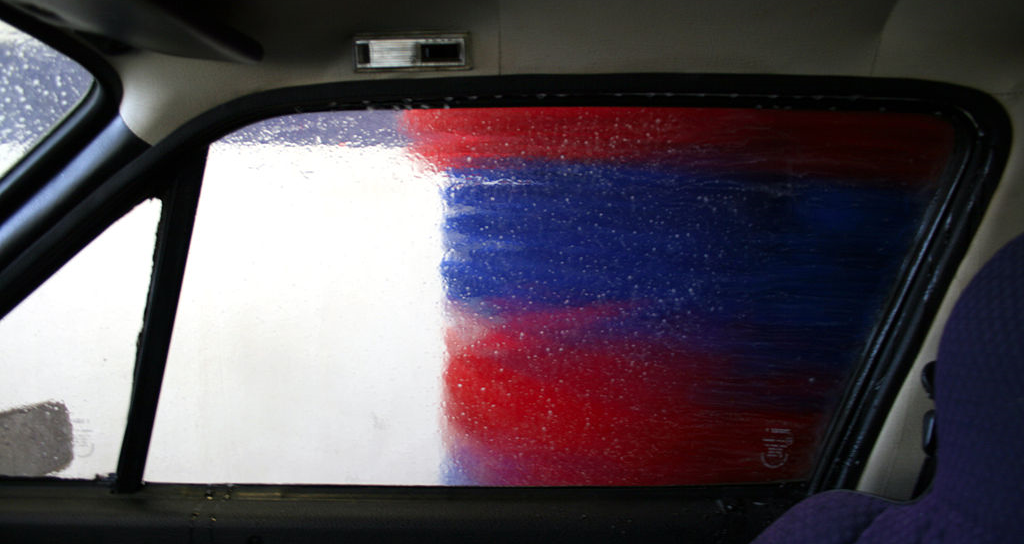

We see this in ‘Car Wash’ (2008). ‘Car Wash’ investigates a small yet potent transgression: ‘two / women in [their] thirties’ kiss as public space affords ‘unexpected privacy’. The women navigate a world of cars and garages more often associated with heterosexual norms and ‘fathers’.

We can see Colette Bryce’s ‘outsiderness’ in this poem: quietly and sensually, the lovers defy mainstream social codes. As with the rope trick, the car wash is a clear, everyday image. At the same time, it stands for complex ideas about public and private lives.

... and between expression and suppression

‘“Say nothing” is still a powerful rule in Northern Ireland’, Bryce tells Alex Pryce: it’s difficult to be outspoken in tight-knit communities that have gone through civil war. For Bryce, though, suppression of speech means suppression of thought. These ideas are behind ‘Don’t speak to the Brits, just pretend they don’t exist’ (you can hear Bryce read and explain the poem in this YouTube video from 2019).

We see ‘The Brits’ of the title, and the bullets from Bloody Sunday, only briefly. Unspoken for the rest of the poem, we can still feel the threat of each in the background, as if they are ‘ready to go off’. Alongside this, Bryce explores cultural and linguistic confusion. Britain’s historical role in this is felt but not voiced: Irish Gaelic is abandoned by teenagers, and pushed aside by a Dubliner’s tongue that insists ‘in English’ on ‘French kissing’.

‘Don’t Speak to the Brits…’ is full of the unsaid and is politically charged. Written in sparse, short stanzas, the poem contains a lot of white space: you might say this suggests gaps in the story and silencing.

In her interview with Adam Wyeth in 2020, Colette Bryce explains she ‘never set out to write “about” The Troubles’. Her work never makes blunt political statements. One of her favourite poetry sayings is Robert Frost’s ‘Poetry is about the grief; politics is about the grievance.’ Her very particular upbringing has given us poems of complexity and compassion.

Sign on the N56 reminding travellers that they are in the Donegal Gaeltacht

Sign on the N56 reminding travellers that they are in the Donegal Gaeltacht

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews