👉 Find out about The Open University's History courses. 👈

The post-Famine period witnessed a continued influx of mainly Catholic Irish immigrants into the United States due to ongoing social and economic change in Ireland and American economic expansion. By the end of the century, the US census indicated that almost five million Americans were either Irish-born or had at least one Irish parent (US Census, 1900). This exceeded the population of Ireland at the time (Kenny, 2000, p. 131)

How were the Catholic Irish received in America?

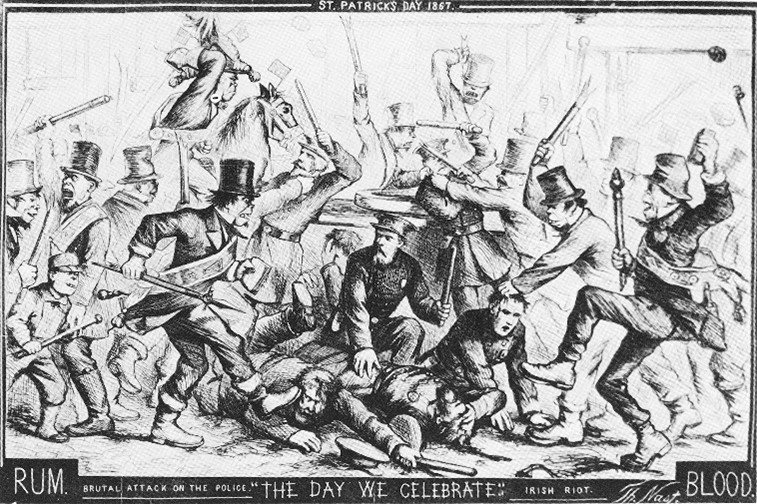

The Catholic Irish who arrived in America in the nineteenth century endured hostility because of their religion and also because of their poverty. The United States was very much a Protestant country that had inherited the prejudices of the colonial era. The Catholic Irish were frequently lampooned in press cartoons for their perceived uncivilised behaviour, and their loyalty to what was seen as an un-American religion led by the Pope in Rome. Many Americans believed that the Catholic Irish could never be integrated into American life. The following cartoon by Thomas Nash, entitled ‘The Day We Celebrate’, appeared in Harper’s Weekly on 6 April, 1867 and reflects contemporary concerns about Irish-Catholic immigrants’ anti-social behaviour: in this case, drunkenness and brawling during St. Patrick’s Day celebrations.

Irish service in the American Military

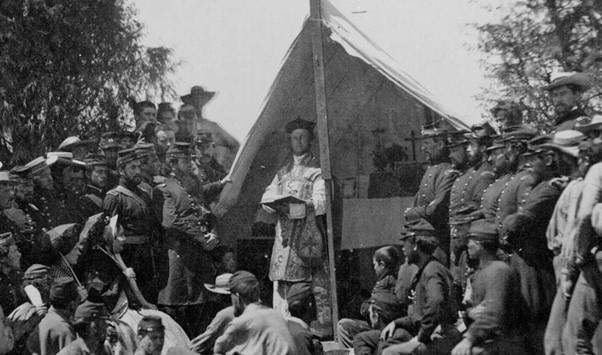

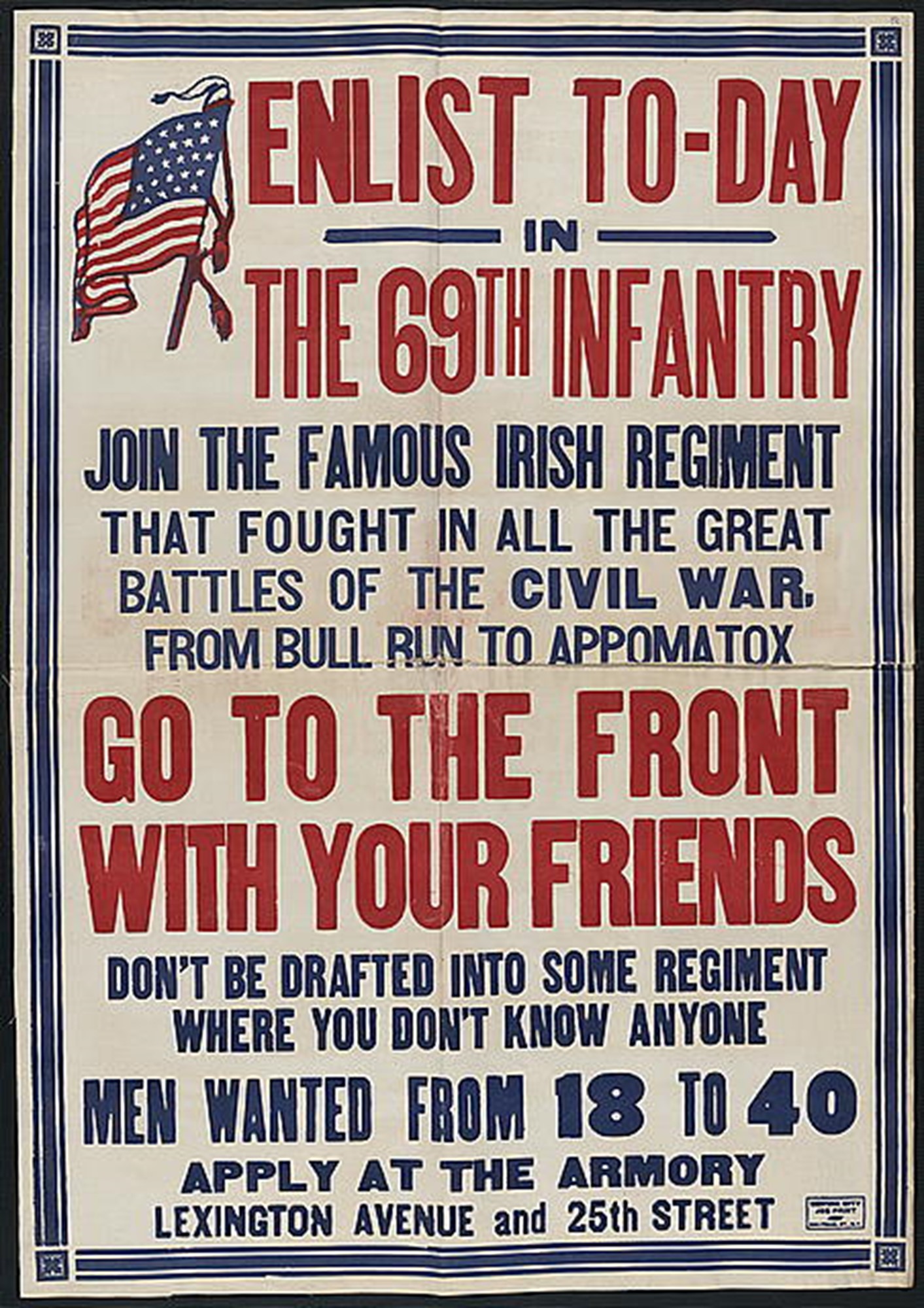

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1860 between North and South impacted heavily on perceptions of the Irish community in the United States. Both the Union and Confederate armies, anxious to attract recruits, formed all-Irish units. Most Irish recruits, an estimated 150,000 men, served with Union forces while about 20,000, generally those who lived in the southern cities such as New Orleans, served with the Confederates. New York’s famous 69th Infantry Regiment was a predominantly Irish regiment in the Union army and took part in many of the bloodiest battles of the war.

Serving under the flag of the United States helped to enhance the Catholic Irish position in the United States by demonstrating Irish loyalty to the American nation as well as their fighting spirit. Following America’s entry into the First World War in April 1917, the US government again sought Irish recruits by appealing to the heroic reputation that the Irish had acquired as a result of their service during the Civil War.

The Catholic Irish and the American Catholic Church

The mainly Irish Catholic immigration of the late 19th century also impacted on the American Catholic Church, which became an Irish- dominated institution. Irish names populated the rosters of clergy across the United States, so much so that the Catholic Irish Priest became a stock character in many Hollywood films in the twentieth century.

This is a photograph of St. Patrick’s Church in New Orleans, which was completed in 1841 to serve the many Irish Catholics who then lived in the city. Interestingly, New Orleans already had a well-established French Catholic Church prior to the Catholic Irish arrival and the Irish failed to gain dominance there until well into the twentieth Century. However, the role of the Irish in the Catholic church in New Orleans was an exception to the general rule. (Doorley, 2001, p. 53).

The Irish in American Politics and Society

For much of its early history, the United States privileged immigrants who were Protestant and white European. As historian William van Vugt points out, in a chapter on American immigration before 1870, British Protestant migrants were generally viewed as ‘invisible immigrants in the sense that they had a comparatively rapid assimilation and were not seen as true foreigners’ (van Vugt, 2013, p. 19).

Yet despite discrimination, by a so-called WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) elite, the Catholic Irish were privileged compared to many other immigrant groups. They were legally white and also largely English speaking. The development of a network of national primary schools across Ireland in the mid-19th century ensured that Irish immigrants had basic literacy skills in English to meet the demands of a modernizing American economy. By 1900 most emigrants who embarked from Queenstown, then the busiest emigration port in Ireland, could read and write (Meaney, O’Dowd and Whelan, 2013, p.89.)

Given their preference for life in the big cities, they were also adept at using the American political system to their advantage, especially in Irish dominated cities such as Boston, New York, and Chicago. Tammany Hall in New York, the headquarters of the Democratic Party, became synonymous with Irish political power in the city.

Such political advantages ultimately allowed the Catholic Irish to move up the social ladder. By the 1920s and 1930s they already slightly exceeded the national average in terms of college participation and professional careers (Akenson, 1996, p. 243). Second generation Irish-Americans were especially upwardly mobile. Daniel Cohalan (1865-1946), whose parents emigrated from County Cork during the famine years, attended Manhattan College, a Catholic institution, and ultimately became a State Supreme Court Justice in 1911 (Doorley, 2019, p.50). Cohalan became a leading figure in Irish-American nationalist movements. In 1919, he and his Irish wife Hanna O’Leary purchased a summer house in Glandore in County Cork which the couple visited every year. Faster ship routes between Ireland and the United States in the early twentieth century facilitated these increasing connections.

The Catholic Irish and the American Presidency

Alfred ‘Al’ Smith (1873-1944), a Catholic, whose grandmother came from County Westmeath, was the democratic candidate in the American Presidential election in 1928. However, he failed to secure victory, in part due to a lingering anti-Catholic sentiment in rural America. John F. Kennedy (1917-1963), was more successful in 1960, becoming the 35th President of the United States. Kennedy’s ancestors came to America from County Wexford during the Famine. He took pride in his Irish heritage and received a rapturous welcome during his visit to Ireland in 1963, just five months before his assassination.

This photograph depicts President Kennedy’s motorcade in Patrick Street in Cork city on the 28th June 1963.

Joe Biden, a Catholic, who was inaugurated as 46th President in January 2021 has family links to County Mayo and Co. Louth. Biden takes pride in his Irish heritage and has quoted popular Irish poets such W.B. Yeats and Seamus Heaney in his speeches. He has also taken a keen interest in the Northern Ireland peace process throughout his political career and visited Ireland in 2016 during his term as Vice President. This photo depicts Vice President Biden visiting Ballina, Co. Mayo on 22 June 2016 accompanied by the then Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Enda Kenny.

The Irish impact on American cities

Compared to other ethnic and racial groups the Irish have been especially prominent in fire and police departments in many American cities. Of the 343 firefighters who died in the 9/11 attacks on New York city in 2001, ‘145 had been members of the fire department’s Irish-American fraternal group, The Emerald Society’ (Meagher, 2006, p.610).

As the Irish became more accepted in the United States, events associated with Irish culture, took on considerable social significance in the American calendar. Today, St. Patrick’s Day is seen as a celebration of Irish culture and identity in many towns and cities and is enjoyed by all Americans. For example, as part of celebrations associated with St. Patrick’s Day (17th March), the Chicago River is dyed green for the day (see photograph below).

Many of the traditions associated with the American parade such as marching bands and decorative floats have also become a feature of St. Patrick’s Day in Ireland. In the following image, a marching band from Louisiana State University marches in the Dublin St. Patrick’s Day parade in 2014.

The Irish Diaspora in America and Ireland today

The Irish diaspora in America continues to play an important role in shaping Ireland’s present and future. In recent decades, successive Irish governments have drawn on the social power of Irish America to further Ireland’s economic and political interests both at home and abroad. Even though the Republic of Ireland is a relatively small country with a population of only 5 million (2021 census), the presence of a large Irish diaspora in the United States has historically provided Irish governments with a powerful source of political leverage in the international arena. This can be illustrated by American participation in the negotiations which led to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 which helped to bring the conflict in Northern Ireland to an end (Kenny, 2000, p. 257).

The Irish Government has also drawn on the close cultural ties with the United States in its quest for American economic investment. According to a report by the American Chamber of Commerce in Ireland, 900 American companies provided employment in 2022 to over 190,000 people with a further 152,000 jobs supported indirectly (2022, p.6). Such investment has played a major role in the transformation of the Irish economy in recent decades and Ireland’s economic growth has led to an influx of migrants from across the globe. According to data released by Ireland’s Central Statistics Office (CSO) in April 2022, about 13% of the Irish population are foreign born (CSO, 2022).

While people from Ireland continue to make their way to America in search of adventure and greater opportunity, Ireland, like the United States, has itself become a nation of immigrants with the attraction of lucrative careers and a much sought after lifestyle. The imprint of the Irish diaspora on America has proved to be deep and enduring, but the American impact on Ireland in recent decades has also been increasingly significant.

Find out more about this project

This article is part of a collection "Coming to America: The Making of the Irish-American Diaspora".

Click here to visit the collection's main page.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews