👉 Find out about The Open University's History courses. 👈

Popular opinion tends to associate Irish emigration to America with the Great Irish Famine of the mid-nineteenth century. However, substantial numbers of Irish emigrants had already travelled to North America since the establishment of British colonies there in the early seventeenth century. These colonies formed part of a single political and economic British world which facilitated trade and passenger traffic from Ireland. After the American Revolution (1775-1783) and the establishment of the United States, these trading networks remained in place and migration from Ireland increased as workers were needed for American industrial expansion in the early decades of the nineteenth century.

There is also a common perception that Irish emigration was mainly Catholic, but this ignores the fact that most Irish migrants to America in the eighteenth century were Protestant. Historian Kevin Kenny estimated that somewhere between 250,000 and 400,000 Irish Protestants crossed the Atlantic in the 1700s (2000, p. 7). The majority of these Protestants were Presbyterians from Ulster, but about a third were from other Protestant denominations and included Anglicans and Quakers from all parts of Ireland (Fitzgerald, 2020, p. 43).

Irish or Scots-Irish?

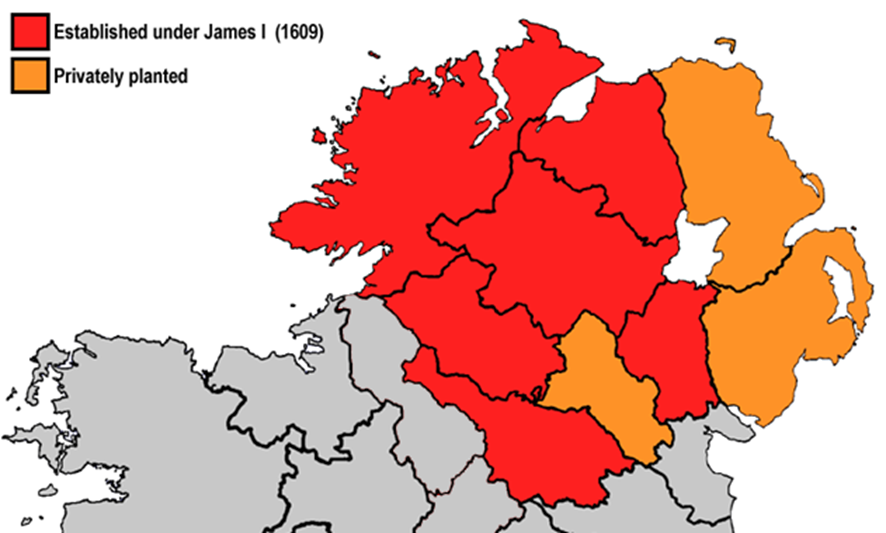

For contemporary observers, Protestant migrants from Ireland who arrived in America in the 1700s were an identifiable group with their own cultural characteristics. They were commonly referred to as ‘Irish’, given that they came from the island of Ireland. However, many were themselves descendants of Scottish and English settlers who had migrated to the north of Ireland during the previous century as a result of the Plantation of Ulster and other English settlements in Ireland.

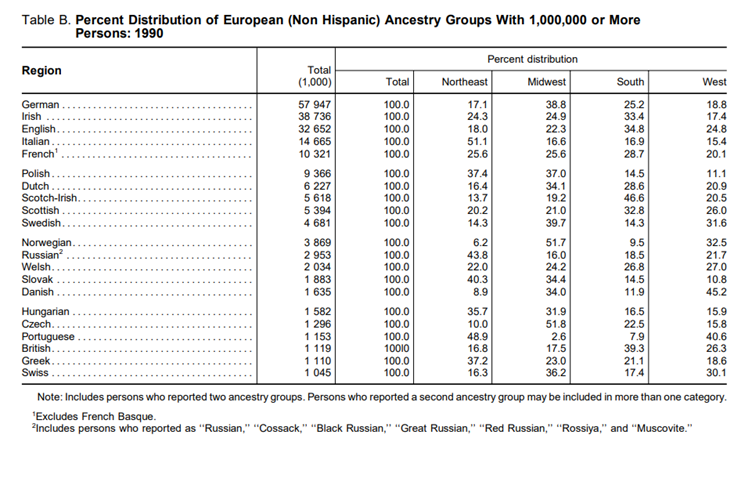

From the 1830s, when Irish Catholics began to arrive in increasing numbers into a then largely Protestant America, many Protestant Irish adopted the appellation ‘Scotch-Irish’ or ‘Scots-Irish’, even though not all came from Ulster and were not necessarily Presbyterian. This label helped to distance them from Catholic migrants who initially encountered widespread discrimination on account of their perceived alien religion and noticeable poverty. In today’s America, use of the term Scots-Irish has declined among those of Protestant Irish ancestry. In the 1990 census, which first allowed Americans to declare a Scotch-Irish background, only 5.6 million chose to identify as such, while 38.7 million Americans, a majority of them Protestant, identified as having Irish ancestry (US Census 1990, Detailed Ancestry Group for States, Table B, 111-4).

Despite the ambiguity around the definition of Scots-Irish, it is still a useful term to differentiate the mainly Protestant Irish migration to America in the eighteenth century, from the largely Catholic migration that took place in the following two centuries. During this earlier period, Catholic migration was discouraged by American colonial governments. Linda Colley argues that at this point in British history there was a strong connection between Protestantism and Britishness, while Irish Catholics were not recognised as part of the British Nation (Colley, 2003).

The association of Catholicism with disloyalty to the Crown was evident in Britain’s American colonies. States such as Virginia and South Carolina even introduced laws to restrict the entry of ‘papists’ into their territories (Kenny, 2000, p. 9). The state of Maryland, one of the original Thirteen Colonies of England, had initially provided a haven for Catholics in the seventeenth century. However, this toleration did not last, and it too introduced a series of penal laws which restricted the rights of Catholics between 1690 and 1720 (Kenny, 2000, p. 72).

Irish Catholics who emigrated in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, often as individual indentured servants, tended to be absorbed into the majority Protestant white population due to the lack of any Catholic Church infrastructure in the colonies. Drawing on the first federal census of 1790, and other secondary sources, Kevin Kenny estimates that between 440,000 and 517,000 of a white population of 3.17 million were Irish or of Irish descent. Kenny also estimates that of the total Euro-American population, only 4% were of Irish Catholic origin and 10% were Irish Presbyterian, while several other Irish Protestant denominations (which included Methodists, Quakers and especially Anglicans) accounted for 2% (Kenny, 2000, p. 42). He also points out that about three quarters of the American Irish were of Ulster origin. Overall, this data highlights how Protestant migrants from Ulster, who were predominantly Presbyterian, played an important role in shaping the Irish diaspora in America during the colonial period.

Find out more about this project

This article is part of a collection "Coming to America: The Making of the Irish-American Diaspora".

Click here to visit the collection's main page.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews