👉 Find out about The Open University's History courses. 👈

Why did the Scots-Irish emigrate?

Emigration to the American colonies in the British colonial period was especially popular among Irish Presbyterians who were mainly located in Ulster. This can be explained by a number of factors. Though they enjoyed a higher social and economic status compared to Catholics, they still endured economic and religious discrimination at the hands of the politically dominant Anglican Ascendancy class. They especially resented having to pay so-called tithes, a form of taxation, for the upkeep of the established Anglican church (Dwyer-Ryan, 2013, p. 98).

Most Presbyterians, because they did not own the land they farmed, were also excluded from Irish political life. Poor economic conditions, especially in the first half of the eighteenth century in Ireland, also played a role. In the period 1739-41, extremely cold summers led to crop failures throughout the entire country and a resulting famine led to the death of between 310,000 and 480,000 people (Kenny, 2000, p. 17). The prospect of being able to work and make a living in the American colonies thus provided a major external incentive to emigrate.

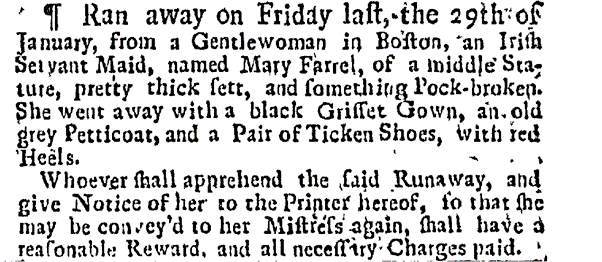

The decision to migrate to the colonies would not have been taken lightly. The sea passage alone took an average of six to eight weeks and was an expensive undertaking. Many of those from poorer social groups, including some Catholics, found that they could only afford the journey through indentured servitude.

Some of the American colonies such as South Carolina offered inducements such as land bounties to attract settlers to the frontier though this was at the expense of the indigenous population who were forced to make way for white settlers. In this context a ‘racial frontier of exclusion’ was deliberately created between white settlers and indigenous communities. This process was replicated in other settlement empires such as Canada and Australia (Fieldhouse, quoted in Hack, 2008, p. 54). Emigrants from Ireland, irrespective of their religion, played a key role in the process of white European colonial expansion into North America.

By the 1760s the Irish economy had improved and become more diversified but migration to the colonies continued. While farm workers were always in demand other migrants with skills in housing construction, shoemaking, printing work and hand loom weaving were increasingly sought after. The development of trading links between Ireland and the American colonies also facilitated passenger travel. For instance, Irish-American partnerships established regular shipping routes between Philadelphia and the Irish ports of Cork, Dublin, Belfast and Derry. Increasingly, skilled emigrants, especially Presbyterians from Ulster, migrated as family groups rather than as indentured servants. In some instances, entire congregations, led by Presbyterian ministers, departed for America. One of the most notable examples of this took place in 1772, when the Reverend William Martin led five shiploads of Ulster Presbyterians, approximately 1,200 people, from the ports of Belfast, Larne and Newry to South Carolina (Sherling, 2013, p. 428).

What was the experience of the Scots-Irish in America?

Protestants from Ireland were generally welcomed to the American colonies but there were some exceptions. The Puritans of New England, even though they shared a similar Calvinist heritage, described the mainly Presbyterian Irish arrivals as ‘Wilde Irish’ and criticised them for their propensity for drunkenness, blasphemy, and violence (Dwyer-Ryan, 2013). Pennsylvania, dominated by a more tolerant Quaker elite, proved to be more welcoming. According to Kevin Kenny, over 100,000 people of Ulster origin lived in this recently established state in 1790 (2000, p. 24).

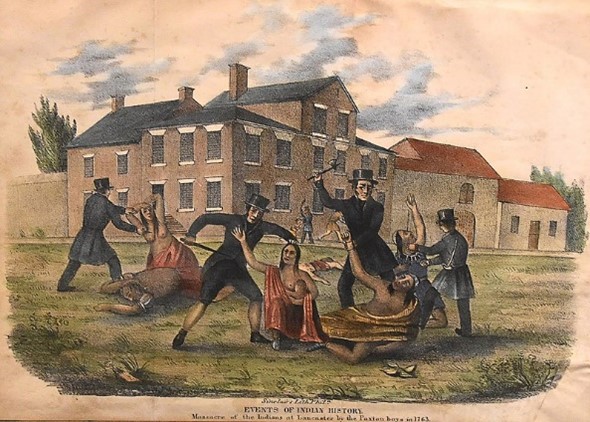

Land on the frontier was cheap and some areas of the American frontier became synonymous with Scots -Irish settlement. These regions included Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and the Appalachian Mountains of western Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Tennessee. In their interactions with indigenous tribes on the frontier, the Scots-Irish gained a reputation for ruthlessness. In 1763, tensions were running high in the aftermath of the French and Indian war which had witnessed Native American attacks on white settlements in western Pennsylvania. In December of that year, a group of Scots-Irish known as the ‘Paxton Boys’ was involved in the murder of twenty peaceful native Americans in what became known as the Conestoga Massacre.

This nineteenth-century lithograph depicts the ‘Paxton Boys’ massacre of a group of peaceful Native Americans belonging to the Susqehannock tribe, called ‘Conestogas’ by the colonial administration. The print was created 78 years after the event.

This massacre appalled the Quaker authorities in the colony who were seeking peaceful co-existence with Indian tribes. Undaunted, 500 armed Paxton Boys marched to Philadelphia protesting about what they saw as the lack of protection provided by the Quaker authorities in the colony. Open conflict was only narrowly averted when a local Quaker official, none other than Benjamin Franklin, who later played a prominent role in the American Revolution, persuaded the marchers to back down (Dwyer-Ryan, 2013).

What role did the Scots-Irish play in the American Revolution?

Irish Presbyterians, who made up the bulk of the Scots-Irish population in Britain’s American colonies, resented the power and influence of the dominant Anglican elite. Given their often frontier location, they also objected to British government restrictions on further westward expansion beyond the Appalachian Mountains. These restrictions were imposed to avoid the costs of further conflict with Native American tribes which would have had to be borne by the British taxpayer (Speck, 2009, p.25). Indeed, the increasing burden of maintaining Britain’s Atlantic empire, and the British desire to place some of this burden on the American colonists contributed to the American revolution which the majority of the Scots-Irish supported.

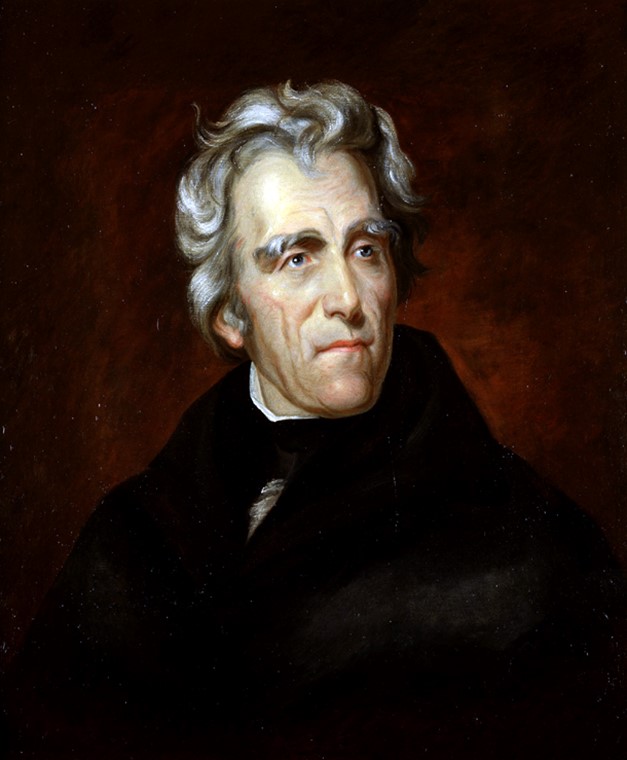

An example of Scots-Irish involvement in the American Revolution can be seen in the short life of Elizabeth Jackson (1740-81). Born in Carrickfergus in County Antrim, she and her husband Andrew left for America in 1765 with her two infant sons. Their third and youngest son Andrew was born on the frontier of the Carolinas. The birth took place shortly after her husband’s death as a result of a logging accident on the frontier. During the revolutionary war, all three boys enlisted in the rebel army. Her oldest son Hugh died in battle while her two younger boys, Robert and Andrew, were taken captive by British forces. Elizabeth negotiated their release in a prisoner exchange though Robert died from smallpox soon after his return home. Elizabeth herself later died from fever in 1781, while tending to wounded American prisoners detained in a prison ship in Charleston Harbour (Lunney, 2021). Her surviving son Andrew later became the seventh president of the United States (1829-37).

Andrew Jackson played a significant role in American history even before his election to the American Presidency in 1829. In the war between the United States and Britain which began in 1812, an American army under Jackson’s leadership decisively defeated a much larger British force at the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815. Ironically, the British army which faced Jackson, was led by Sir Edward Packenham, a member of the Anglo-Irish establishment, who owned estates in County Westmeath. Packenham was killed in action during the battle.

Jackson’s fame contributed to his successful bid for the American presidency. However, more controversially, when President, he signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. This measure reflected a continuation of the racial settlement policy of the colonial authorities. It authorised the forced relocation of Indian tribes living East of the Mississippi river further westward so as to facilitate white settlement. It has been estimated that at least 3,000 Native-Americans died during the forced march westwards in what the Cherokee called the ’Trail of Tears’ (Thompson, 2000, p. 197).

What was the impact of the Scots Irish on American life?

Despite their fearsome reputation on the frontier, the Scots-Irish contributed much to American colonial life and the newly established United States. Presbyterian ministers were renowned for their learning and founded many schools, especially on the frontier. School professor and Scots-Irishman William Holmes McGuffey is credited with the production of America’s first school primer which became available in most American schools in the later nineteenth century.

The Scots-Irish also contributed to American musical traditions. According to Mick Moloney, a professor of music at New York University, the songs and instrumental music brought by the Scots-Irish to America ‘blended with English, Scottish, African-American, and possibly Cherokee traditions, creating a genre that is now called old time, old timey, hillbilly, or Appalachian music’ (Moloney, 2006, p. 282). Examples of Appalachian music and its Scots -Irish roots are available here.

The term ‘Bog-Trotter’, which dates from the seventeenth century, was an English slang word used to describe the lower class of Irish peasantry. The name of the band would itself denote a link to Ireland. The nature of the music played as well as both fiddles would also suggest strong Scots-Irish and Irish roots. Other cultural influences are also visible such as the banjo, an instrument originally from West Africa which arrived in America as a result of the slave trade.

Find out more about this project

This article is part of a collection "Coming to America: The Making of the Irish-American Diaspora".

Click here to visit the collection's main page.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews