👉 Find out about The Open University's History courses. 👈

Social and economic changes in both Ireland and the United States can be used to explain shifting patterns of Irish emigration in the nineteenth century. By the early 1830s, Irish Catholic migrants to America began to outnumber their Protestant counterparts, though the latter still remained a significant proportion of Irish emigration. The Act of Union of 1801, which abolished the Irish Parliament, removed the ability of a local government, even one dominated by the Anglican Ascendancy class, to nurture and protect Irish industry. The Industrial Revolution was now in full flow in Britain, but except for those areas surrounding Belfast, Ireland experienced de-industrialisation as its native industries were unable to compete with cheaper British imports. Meanwhile, in America, as in Britain itself, workers were needed for manufacturing industries and for infrastructural projects such as the construction of canals and railways. Irish labour would help to meet this demand.

Changes in the agricultural sector also incentivised Irish emigration. Given Ireland’s colonial past, most of the land was held by a relatively small number of Anglo-Irish landlords who derived a significant portion of their income through rents from tenant farmers. The social and political power of the Anglo-Irish elite in nineteenth-century Ireland was symbolised by the ‘Big House’.

A typical example of the Big House is Blarney House in County Cork which was first built by the St. John Jefferyes family in 1874. The house was designed in the Scottish Baronial style, a type of architecture associated with the Gothic Revival.

The role of the ‘Big House’ in Irish history is explored in the Open University module A111, Discovering the arts and humanities.

Many of the owners of such houses also maintained estates in England and in other parts of the British Empire. The management of an Irish estate was frequently left in the hands of middlemen, often Catholic, who focused their attention on maximising rents from tenant farmers rather than on agricultural improvements. These farmers in turn rented small potato plots of their land to an impoverished class of labourers or ‘cottiers’ in return for the labour services required to produce tillage crops. Given the semi-feudal nature of the Irish rural economy, Ireland witnessed an exponential rise in population in the early decades of the nineteenth century. Rapid population growth took place especially among the labourer/cottier class who subsisted mainly on a potato diet. In 1784, the population of Ireland was estimated to be 4 million people but by 1841, according to the Irish census of that year, it had doubled to over 8.2 million (Kenny, 2000, p. 46).

The fall in the price of corn and other tillage crops after the Napoleonic wars encouraged a trend towards cattle production. Also, because of the industrial Revolution in Britain and the growth of cities, the owners of agricultural land now had a growing urban market for dairy and meat products. Cattle production was much less labour intensive compared to tillage farming, and even before the Famine, landlords had these market incentives to reduce the number of their tenants.

Population pressures, lack of employment and the existence of employment opportunities in the United States led to increasing emigration from rural Ireland. The American Revolution, which had emphasised religious toleration, also improved the standing of Catholics, at least in a legal sense. Charles Carroll, a prominent Catholic from the state of Maryland, was a signatory of the Declaration of Independence. His relative John Carroll was ordained as the first bishop of the United States in 1790 in Baltimore. Religious toleration and the development of a Catholic infrastructure in Maryland and in other states also made the United States more attractive to Catholics (Kenny, p. 73).

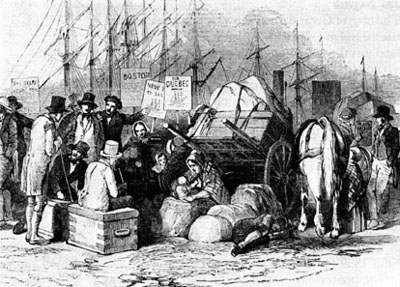

Between 1815, which marked the end of the Napoleonic wars, and 1845, the year the famine began, somewhere between 800,000 and 1 million people left Ireland for the United States and Canada. Kenny estimates that by 1840 only 10% of Irish migrants were now Protestant, though, given the increased numbers leaving Ireland, this still represented a considerable number of Irish emigrants (2000, p. 45).

Many Irish emigrants who took the cheaper Canadian route eventually made their way to the United States. The southern port of New Orleans, because of its strong trading links with Liverpool, also became a major port of entry for immigrants until the American Civil War (Doorley, 2000, p. 36).

Women of the Irish Emigration

Unlike the Scots-Irish settlers of the eighteenth century, Irish migrants to the United States in the nineteenth century tended to settle in cities such as Boston, New York and Chicago, though many Irishmen also laboured on canal and railway construction projects across the country. While the initial wave of Irish Catholic emigrants was predominately male, Irish women began to emigrate in increasing numbers, often escaping from the patriarchal social strictures of rural Ireland. Historians Geraldine Meaney, Mary O’Dowd and Bernadette Whelan point out that Irish women, because of developments in literacy and transatlantic communications, became aware of the opportunities available to them in the United States and could thus prepare for the challenges that would meet them across the Atlantic (Meaney, O’Dowd and Whelan, 2013, p.89).

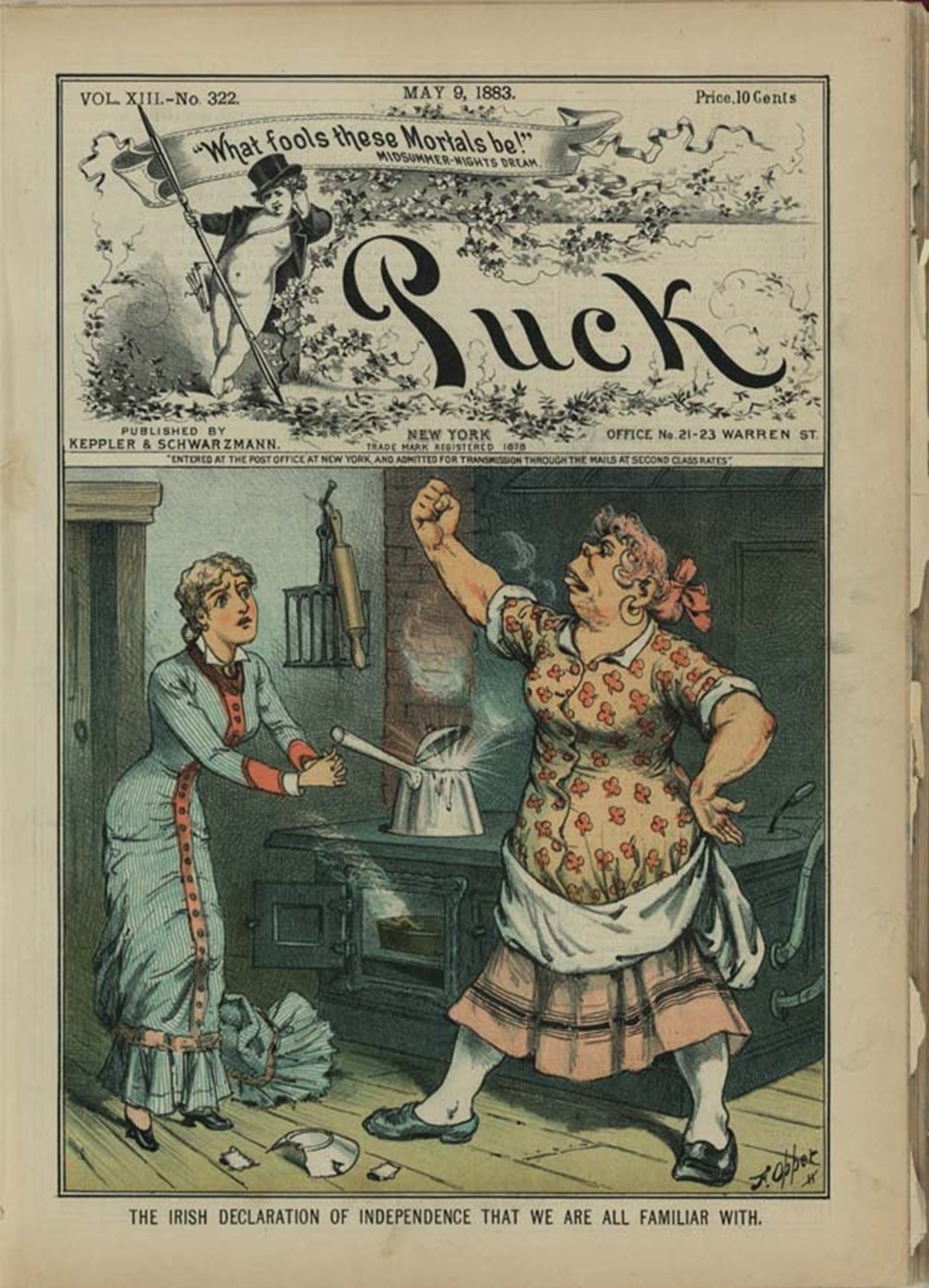

According to historian Hasia Diner, Irish women came to account for 52% of total Irish migration in the nineteenth century (Diner, 1984, p.31). This was unusual in comparison with other European groups where men predominated. Many Irish women found work as domestics catering to America’s growing middle class. Indeed ‘Bridget’, often portrayed in cartoons as inept and ‘manly’, became a typical stereotype of an Irish domestic servant in American vaudeville theatre productions in the early 1900s (Kibler, 2015, pp. 3-7).

Yet such women worked long hours in domestic service and sent what they could to their relatives left behind in Ireland. What the Irish referred to as ‘The American letter’ often contained money which ensured the survival of those left behind and facilitated the migration of other family members. As historian Margaret Lynch-Brennan points out, many such women ‘came in a chain migration in which male and female relatives brought over other family members over time’ (Lynch-Brennan, 2007, p. 333).

This painting, by Galway artist James Brennan (1837–1907), depicts the interior of an Irish cottage in post-famine Ireland where a young girl reads a ‘Letter from America’ to her parents and older sister.

The Great Famine and Irish Emigration

The failure of the potato crop in 1845, combined with an inadequate British government response to the crisis, led to the Great Irish Famine of 1845–1850 and the deaths of approximately 1 million people. The majority of deaths occurred among the labourer and cottier class who depended on the potato for their survival. Emigration, which was already increasing before the Famine, now became a flood but only those with sufficient means could afford the journey to the United States. Nevertheless, during the period of the Irish Famine and its aftermath (1845–1854), approximately 1.7 million people left Ireland for America (Emmons, 2013, p. 88).

Irish emigration to North America during the Famine years had a "panic quality" which was very different to previous and later waves of Irish emigration. While the majority of famine emigrants survived the difficult journey, thousands did not. The year 1847, known in Ireland as ‘Black 47’, was especially harrowing in terms of emigrant mortality. Ships leaving Ireland were overcrowded and many poorer emigrants, weakened by hunger, were vulnerable to diseases such as measles and consumption. Many poorer emigrants chose the cheaper Canadian route to North America but this was also the more dangerous. Ships carrying diseased passengers often had to wait for long periods before docking at quarantine stations at North American ports. This inevitably led to the spread of disease and high mortality aboard what became known as ‘coffin ships’. In May 1847, an estimated 20,000 Irish emigrants perished from disease in the vicinity of the quarantine station at Grosse Île outside Quebec City. The overall total number of emigrants who died in such circumstances on both the Canadian and United States route in 1847 is thought to be about 50,000 (Donnely, 2002, p. 181).

The Famine accelerated the structural changes that had begun in Ireland after the Napoleonic Wars. The north-east of Ulster became an integral part of Britain’s industrial economy while the agricultural system in the south of Ireland gradually became more commercialised. Cattle production for the British market dominated the post-Famine agricultural landscape and the demand for agricultural labour continued to decline. Meanwhile, both Britain and the United States appeared to have almost insatiable demand for industrial labour. If the Famine had not taken place, it seems most likely that emigration would have continued to be a feature of Irish life, especially from the south of Ireland, though without the terrible mass mortality of the 1840s (O’Grada,1993, p.41).

Find out more about this project

This article is part of a collection "Coming to America: The Making of the Irish-American Diaspora".

Click here to visit the collection's main page.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews