State renewal and repair in Northern Ireland

The creation of Northern Ireland in 1921 demonstrates that the link between a state, its territory and the people within these territorial boundaries is not pre-given. Following the War of Independence with Britain from 1919 to 1921, the partition of Ireland in 1921, as a result of the Government of Ireland Act in 1920, led to the creation of an independent Irish Republic in the south and a British-controlled Northern Ireland (see right). Northern Ireland’s territorial boundaries were drawn by the British Government in order to incorporate as much as possible of the large Protestant population of Ulster who had opposed Home Rule in the wake of partition in favour of union with Britain.

The creation of Northern Ireland in 1921 demonstrates that the link between a state, its territory and the people within these territorial boundaries is not pre-given. Following the War of Independence with Britain from 1919 to 1921, the partition of Ireland in 1921, as a result of the Government of Ireland Act in 1920, led to the creation of an independent Irish Republic in the south and a British-controlled Northern Ireland (see right). Northern Ireland’s territorial boundaries were drawn by the British Government in order to incorporate as much as possible of the large Protestant population of Ulster who had opposed Home Rule in the wake of partition in favour of union with Britain.

At the heart of the politics of Northern Ireland is a divided population that experiences the state in quite different ways. In simplified terms, a majority in Northern Ireland, although they represent only a minority in Ireland as a whole, regard themselves as British and want Northern Ireland to remain a part of the United Kingdom. This majority of Unionists, and their radical form, the Loyalists, are also predominantly Protestant. A sizeable minority within Northern Ireland, 44 per cent according to the 2001 Census, define themselves as Irish and Catholic, although an increasing number of people do not see themselves as belonging to either category. The Catholic Nationalists, and their radical form, the Republicans, would prefer to be ruled by a single, Irish authority. For the Catholic minority within Northern Ireland, the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921 established ‘an artificial state, devoid of geographical, historical or political logic’ (Tonge, 2001, p. 634). Both the Protestant majority and the Catholic minority, however, are not static. The size of the majority and minority fluctuates over time. Moreover, both within and outside this majority and minority, other majorities and minorities based on gender, age, sexual orientation, disability, ‘race’ and ethnicity, for example, coexist.

The tradition of mural painting in Northern Ireland provides an insight into the political dynamics of these changing communities. When and where murals appear, what they express and what they don’t express, how they are renewed and repaired or how they are forgotten and left to fade provide insights into the political process and the ways in which power is expressed and contested in Northern Ireland.

In the following audio clip, Bill Rolston, Emeritus Professor, Transitional Justice Institute, Ulster University, explains to OU Associate Lecturer Roisin Kelly why murals are of interest to him as a social scientist:

Roisin Kelly: Hello Bill. I just want to ask why are murals of interest to you as a social scientist? What made you want to study them?

Bill Rolston: If it doesn’t sound too much of a cliché, because they’re there is the first answer. Let me explain that. In 1981, there was quite literally an explosion of murals in Belfast and other parts of the North in Nationalist and Republican areas in support of the hunger strike. Now, this was unusual in that Nationalists and Republicans, for the most part, hadn’t painted murals before, so you couldn’t miss what was happening, this transformation of the areas. I started photographing them then, and I’ve been photographing them ever since – both Republican and Loyalist murals. But a slightly more sociological answer, I suppose, is to say that, as a sociologist, I’ve been very interested, in all the years of my research and my teaching, in community activism, community politics, and these murals are a wonderful window into communities, what communities think, what communities fear, what the odds are for communities to find a new vision to replace an old vision, and so that they are wonderful tool for that.

For cultural historian and museum exhibition designer Judy Vannais (2001), there are two separate traditions of mural painting in Northern Ireland which are indicative of two different relationships to the state. On the one hand, the Unionist/Loyalist tradition of mural painting has been going on for more than a century. This long tradition denoted a community at ease and confident in its relationship with the state. Mural painting was an expression of this confidence and it literally represented a claiming of public space and territory, and an assertion of identity and belonging, that was evidence of the Protestant domination of politics and society in Northern Ireland. Prior to the 1970s, the majority of Unionist/Loyalist murals were linked to the annual commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne on 12 July 1690, when Protestant Prince William of Orange defeated Catholic King James II in the struggle for the English throne. The dominant image in these murals was of ‘King Billy’ astride his white horse crossing the River Boyne (left).

For cultural historian and museum exhibition designer Judy Vannais (2001), there are two separate traditions of mural painting in Northern Ireland which are indicative of two different relationships to the state. On the one hand, the Unionist/Loyalist tradition of mural painting has been going on for more than a century. This long tradition denoted a community at ease and confident in its relationship with the state. Mural painting was an expression of this confidence and it literally represented a claiming of public space and territory, and an assertion of identity and belonging, that was evidence of the Protestant domination of politics and society in Northern Ireland. Prior to the 1970s, the majority of Unionist/Loyalist murals were linked to the annual commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne on 12 July 1690, when Protestant Prince William of Orange defeated Catholic King James II in the struggle for the English throne. The dominant image in these murals was of ‘King Billy’ astride his white horse crossing the River Boyne (left).

The Nationalist/Republican tradition of mural paintings, on the other hand, dates only from the beginning of the 1980s, though attempts to claim territory through painting slogans, for example, pre-dated mural paintings. The late development of mural painting as an expression of the Nationalist/Republican community, in comparison with the early development of Unionist/Loyalist painting, is indicative of a very different relationship to the state. Nationalists and Republicans in Northern Ireland generally rejected the idea of Northern Ireland as a separate state and did not feel that the state belonged to them. The state’s laws and daily practices were a constant reminder that the Nationalist/Republican community was a minority in a state that belonged to the majority Unionist/Loyalist community. Nowhere was this exclusion felt more strongly than in the policing of Northern Ireland. Jon Tonge notes that the Special Powers Act of 1922 gave the predominantly Protestant security forces in Northern Ireland vast and arbitrary powers. The Royal Ulster Constabulary averaged only 10 per cent Catholic membership while the auxiliary police force, the B Specials, was exclusively Protestant (Tonge, 2001, p. 634). For Catholics, there was nothing legitimate about the state’s claim to a monopoly of force in Northern Ireland.

In this clip, Bill Rolston discusses the function of the murals and explores the relationship between different communities, their territories and the state:

Roisin Kelly: So what do you think the actual function of the murals is?

Bill Rolston: In the first instance, they speak to the community which they’re in, and this is a very important point to get across, I think. Sometimes, there’s a sort of a, at the risk of offending fellow social scientists, a sort of anthropological bias which says that they’re painted on the edge of areas, about marking out territory and about keeping out strangers and foreigners and all sorts of things. In point of fact, in the first instance, they’re much more located in the community and talking into the community. So, geographically, they’re frequently in the heart of community rather than the edge. And what their function is, ideologically and politically, is to say to the community, ‘Look, this is the position on whatever.’ This is, you know, the UDA’s position on such and such; this is the IRA’s position on such and such. Are you one of us? Are you with us on this? This is the position. So you could call them political education, or you could call them mobilisation of support, but whatever, in the first instance they’re about the local community. As time has gone on, they’ve had some other functions, to some extent. Loyalists in particular have done sort of territory-marking murals, but that’s mostly against other Loyalist groups. And also, increasingly in the peace process, some of the murals are done with one eye looking toward the tourist trade and the number of tourists that will come into an area.

Roisin Kelly: So what do these murals then say about the relationships between different communities, their territories and the state?

Bill Rolston: There’s a very deferential relationship between each of these communities and their murals and the state concerned, the Northern Ireland / British state. If I can run through it very quickly. Loyalist murals have been, from the very beginning a hundred years ago, pro-state murals, and it’s important to think of both aspects of that term, pro-state. They’re not state murals, they’re not sponsored; you know, this is not Saddam Hussein painting murals around the place, for example. They’re not paid for by the state for the most part and they’re not commissioned by the state, but they’re painted by a group of people who see their role as being merely an extension of the state. Just as Loyalist paramilitary groups have seen themselves as an extension of the state security forces, the muralists see themselves as some sort of cultural wing of the state. Now the state sometimes has agreed with them on that and sometimes hasn’t agreed with them on that. And the point is that sometimes the state for which the Loyalist murals are pro, if you know what I mean …

Roisin Kelly: Mm.

Bill Rolston: … it’s a state that’s in their imagination. It’s the state they aspire to and the real state does not go along with them. So sometimes you will find opposition, frustration, even pro-state contradictions in the murals, but ultimately, the bottom line is they are for the state that Loyalists would want in Northern Ireland. Republican murals are simpler to explain for the most part. They’re anti-state. That’s it. End of story. [laughter] And so, from the very beginning, they’ve been opposed to the state’s position on, for example, the hunger strike, or the state’s position on plastic bullets, or the state’s position on, you name it. More interestingly, if I can just bring this story up to date, the problem for both of these sets of murals is that you sometimes get a hint of a reversal going on, in that you will get Republican murals that are very, very pro some state policies, – for example, the Good Friday Agreement. Whereas the pro-state mural painters are anti the state’s policy on the Good Friday Agreement, for example. So you get a funny sort of reversal going on there sometimes. But that possibly explains it.

The late development of Nationalist/Republican mural painting, therefore, denoted a community which felt excluded from the state and feared showing its identity in public. Events in the 1970s, however, forced a change in the politics of Northern Ireland and in community relations, and these changes were reflected in changes in the two communities’ mural painting traditions. Influenced by similar movements in the USA, in the 1960s the Nationalist/Republican communities began a series of civil rights marches demanding an end to discrimination against Catholics in the political, economic and social spheres. Specifically, Catholics demanded police reform and a fairer voting system to end Unionist domination of the political system in Northern Ireland, where Unionist Party control of the parliament at Stormont from 1922 to 1972 was matched by Unionist control of 85 per cent of local councils (Tonge, 2001, p. 634). Political discrimination was reinforced by discrimination in education, housing provision and employment.

The increasingly harsh response by the police, and ultimately the British military forces, to the civil rights movement led to a spiral of violence that marked the beginning of the ‘Troubles’. The last big civil rights march, on 30 January 1972, became known as Bloody Sunday following the killing of fourteen civilians by British soldiers. Later in 1972, the Northern Ireland parliament was dissolved and direct rule was imposed from Westminster. The state’s claim to its monopoly of legitimate force was challenged directly, on the one hand by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), a left-wing paramilitary organisation that sought to bring about a united Ireland, and on the other hand by various Loyalist paramilitary groupings, such as the Ulster Volunteer Force, the Ulster Defence Association and the Ulster Protestant Volunteers, which fought to maintain Northern Ireland’s status within the UK.

Although the onset of the ‘Troubles’ curtailed the civil rights movement’s reclaiming of public space through protest marches, the Nationalist/Republican community began to assert its control of public space visually through an explosion of mural painting. The main catalyst for change was the hunger strike of 1981 by Republican prisoners demanding the reinstatement of their prisoner-of-war status which had been revoked by the British authorities in 1976. From this moment onwards, the Nationalist/Republican community began to use mural painting in much the same way that it had long been used by Unionists and Loyalists, namely, to demarcate territory and affirm their identity. Murals were a means of communication which aimed to get across a message that was often suppressed and denied in the media. Murals honouring the hunger strikers, especially Bobby Sands (left), proliferated.

Although the onset of the ‘Troubles’ curtailed the civil rights movement’s reclaiming of public space through protest marches, the Nationalist/Republican community began to assert its control of public space visually through an explosion of mural painting. The main catalyst for change was the hunger strike of 1981 by Republican prisoners demanding the reinstatement of their prisoner-of-war status which had been revoked by the British authorities in 1976. From this moment onwards, the Nationalist/Republican community began to use mural painting in much the same way that it had long been used by Unionists and Loyalists, namely, to demarcate territory and affirm their identity. Murals were a means of communication which aimed to get across a message that was often suppressed and denied in the media. Murals honouring the hunger strikers, especially Bobby Sands (left), proliferated.

At the same time, political scientist Jean Abshire (2003, p. 152) argues that these early Nationalist/Republican murals also reflected the changing strategy of the Republican political party Sinn Féin, whose new slogan ‘Not everyone can plant a bomb, but everyone can plant a vote’ aimed to combine the armed struggle of the IRA with increased political engagement, particularly following the election of Bobby Sands to the House of Commons while on hunger strike.

The long peace

For Vannais (2001, p. 138), the 1994 ceasefires by both Republican and Loyalist paramilitary groupings not only represented a new beginning, which would eventually culminate in the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, they also marked a new phase in mural painting. She argues that most Nationalist/Republican mural paintings seemed to anticipate the ceasefire signed by Republican paramilitaries on 31 August 1994, while most Unionist/Loyalist paintings seemed to struggle to acknowledge the ceasefire had taken place long after it had been signed on the 13 October 1994.

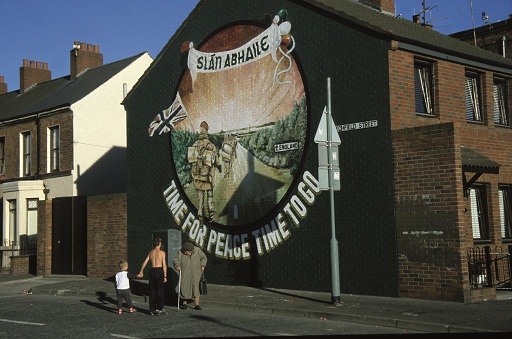

By 1994, British troops had been in Northern Ireland for twenty-five years. This anniversary was signalled by the appearance in Nationalist/Republican murals of a circular stencilled emblem which read ‘Time for Peace – Time to Go’ with the number 25 painted in the centre. Vannais (2001, p. 139) argues that this emblem, which became ubiquitous in Republican areas in the months leading up to the 1994 ceasefire, was a message directed not only at British troops but also at fellow Republicans. Vannais describes one Republican mural painted by Danny Devenny several months before the IRA ceasefire that appeared on gable walls throughout Belfast. The image is of a line of British soldiers marching down a road signposted to England. A banner above the soldiers, decorated with green, white and orange balloons, wishes the troops Slán Abhaile (‘safe home’ in Irish) and below this is the message: ‘Time for Peace, Time to Go’ (left). Vannais (2001, p. 140) argues that what is remarkable about this image is how magnanimous the message is, given the levels of hostility against the British Army at that time.

According to Vannais (2001, p. 142), the optimism and magnanimity that characterised the Republican/Nationalist murals in the period leading up to the 1994 ceasefire were not present in the Unionist/Loyalist paintings. As Nationalists and Republicans became increasingly assertive and confident in their public identity, Unionists and Loyalists were beset by uncertainty and a lack of confidence. Loyalist murals reflected this changing political landscape as the King Billy theme, which had predominated until the 1970s, began to be replaced by paramilitary themes (left).

According to Vannais (2001, p. 142), the optimism and magnanimity that characterised the Republican/Nationalist murals in the period leading up to the 1994 ceasefire were not present in the Unionist/Loyalist paintings. As Nationalists and Republicans became increasingly assertive and confident in their public identity, Unionists and Loyalists were beset by uncertainty and a lack of confidence. Loyalist murals reflected this changing political landscape as the King Billy theme, which had predominated until the 1970s, began to be replaced by paramilitary themes (left).

This uncertainty continued up until and after the 1994 ceasefires, when the message in loyalist murals became more militaristic and demonstrated none of the sense of impending change that could be found in the Nationalist/Republican paintings. It could be argued that this represents an example of zero-sum power, where gains by one side are perceived as losses by the other.

From the 1970s onwards, therefore, mural painting developed in each community in diametrically opposed ways. This trajectory continued through the ceasefires of 1994, into the political negotiations that followed and beyond the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, which was the culmination of this process. Following the 1998 Agreement, Nationalist/Republican murals engaged with the process. Some were genuinely supportive of the new political structures put in place by the Good Friday Agreement, while others were critical of the way in which some aspects of the agreement were implemented (left).

From the 1970s onwards, therefore, mural painting developed in each community in diametrically opposed ways. This trajectory continued through the ceasefires of 1994, into the political negotiations that followed and beyond the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, which was the culmination of this process. Following the 1998 Agreement, Nationalist/Republican murals engaged with the process. Some were genuinely supportive of the new political structures put in place by the Good Friday Agreement, while others were critical of the way in which some aspects of the agreement were implemented (left).

Loyalist paintings, on the other hand, were much more hesitant in engaging with the political process. This reflected the difficulties that the peace process posed for Unionists and Loyalists. Given that this community desired continued union with the UK, it is perhaps not surprising that the murals did not depict the same sense of change that the Nationalist/Republican murals did. On the contrary, they continued to depict Loyalist paramilitary gunmen, often with the slogan ‘No Surrender’. These militant murals served as a warning message both to Nationalists/Republicans and to their own politicians who were engaged in the negotiations. This is indicative of the ambivalence felt by many in the Unionist/Loyalist communities towards the peace process as well as the tensions between various paramilitary factions within the community.

In 2008, ten years after the implementation of the Good Friday Agreement and only one year after the historic power sharing in government that began in May 2007, a mural Painting from the Same Palette was unveiled at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the USA.

In this clip, Bill Rolston explores the relationship murals have with the past, present and future and comments on the mural:

Bill Rolston: If you look at the peace process, what you find is that it’s Republicans, although they have been shaky on it at times, they have been basically on the one trajectory, and so the murals reflect that. For example, from 1998 on, it became clear that Republican muralists were not any more going to paint guns in their murals. So the only guns that you’ll see in murals in the last decade or so on the Republican side have been in historical murals or memorial murals to dead comrades. On the Loyalist side, their attitude to the peace process has been a lot more wobbly. And the result has been that they have been very, very, very reluctant to give up the paramilitary belligerent imagery that they’ve had in the murals. It became more and more anachronistic as time has gone on and they came under severe pressure to take their guns and their hooded gunmen out of their murals. There’s thankfully now a good lively debate going on within loyalism and they’re beginning to change, but partly because the state has provided, over the last few years, three-and-a-half million pounds of money to groups to paint out the belligerent murals and paint something else instead. So, the past is being painted out of the murals in some way, with the possible exception at the moment of some historical and some memorial murals, and this has led to a debate on both sides as to say whether the point is now that we should literally paint over the past or whether we have a duty to acknowledge the past and the suffering that people went through in the past. So, the jury’s still out as to which way this is going to go but what I would say is that the trick that the muralists are trying to find is to move on while, at the same time, not ignoring what happened in the past. And a little bit like one of the murals that’s reproduced in the Open University book which says that history’s like looking in a rear-view mirror: you have to look where you came from, but if you don’t keep your eyes on the road ahead you’re not going anywhere. It’s colourful, it’s vibrant, it’s thoughtful, and what is not apparent when you just look at it, but when you’re told the story becomes very important about the mural, is that it was painted by two people from, coming from different sides, Danny Devenny, who comes from the Republican side and has been painting murals for many years, and a younger man, but also a very proficient and able mural painter, Mark Ervine on the other side. They’ve painted that, they’ve painted Guernica, they’ve reproduced Guernica on a wall in west Belfast, they’ve done some murals in Liverpool, and they’ll be going to the States to follow up on that Painting From the Same Palette mural, to do some other work in the United States.

What was unusual about this mural was that it was painted by Danny Devenny, a former IRA prisoner and famous Republican muralist, and Mark Ervine, a famous Loyalist muralist. According to Danny Devenny: ‘During the war, the murals told the story of injustices we experienced. Now they show hope for the future’ (quoted in UMassAmherst College of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2008). Mark Ervine commented that while previous murals reflected the communities’ concerns about the conflict: ‘Now hopefully this is the beginning of ones that will reflect the peace’ (quoted in UMassAmherst College of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2008). The two artists have continued to work together, most recently on a series of murals depicting the Beatles to celebrate Liverpool’s term as Capital of Culture in 2008.

These different developments in the murals of each community demonstrate the changing relationship of each to the state. They also express changes in the balance of power as murals are created or removed in attempts to demonstrate control over space and place. This case study of mural painting clearly reveals a distinctive and localised way in which disputes over ordering and legitimation claims manifest themselves and change over time, and the important role that symbols and images can play in such processes. As Republicans and Nationalists became more confident and secure in their relationship with the state, the murals began to demonstrate a more commemorative attitude, in much the same way that the early Unionist/Loyalist murals demonstrated their confidence through murals commemorating 12 July. Conversely, new murals by Loyalists and Unionists (left) seek to move beyond paramilitary themes to depict new and broader cultural and historical themes, often borrowing icons used by Nationalist/Republican murals in much the same way that Nationalist/Republican murals sought legitimacy for their struggle when they began painting murals in the 1980s (Vannais, 2001, p. 156).

So, what can we learn from the mural case study about the state and the relationship between citizens and the state? Here’s what Bill Rolston has to say:

Bill Rolston: There are many things. The state is a big issue and the relationship to the state in somewhere like Northern Ireland where the question of legitimacy is constantly up for grabs, it’s a complex story and it’s a bit difficult to sum it all up in a few sentences, but there is one point I would like to focus in on and that is the extent to which these murals have been a voice for the community and a voice that the state didn’t always want to hear. Especially on the Republican side, they didn’t want to hear this message, and from time to time they didn’t want to hear the Loyalist message either. Now, it seems to me that the trick is for the muralists to continue to paint murals that articulate the beliefs, fears and visions of those communities, even if the state doesn’t like that, even if it is off-message. And it seems to me that, at the moment, the balance is a little bit on the state side, where the state is sponsoring the repainting of the murals which is fine and some of the murals they’ve sponsored have been good, enjoyable murals, but it seems to me that there’s a sort of agenda, not all that hidden, in the state’s purpose which is to say, ‘Let’s take the politics out of the murals.’ If that’s the case, then a very old tradition here, a century old tradition, will have been dealt a death blow, and I think it’d be a terrible shame, not just for people like me who look at them and photograph them, but a terrible shame for people in the communities who are able to use this medium to voice their opinions and to get those opinions across, when many other media were forbidden to them.

It is still too early to say what the fate of Northern Ireland’s murals will be, but there are indications that the tradition may evolve rather than disappear, not the least because they are an increasingly popular tourist attraction.

This article is an adapted extract from the free course 'Political Ordering', which is adapted from the Open University course Introducing the social sciences (DD102).

Mural photographs © Bill Royston

Painting from the Same Palette © Mark Ervine and Danny Devenny

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews