5 High-energy reactions

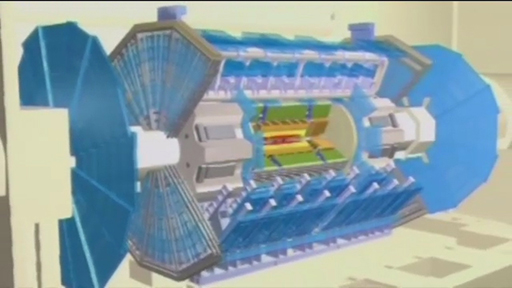

In particle accelerators, or in the Earth’s upper atmosphere, hadrons can smash into each other with large kinetic energies and create new hadrons from the debris left behind. The following short video was made while the ATLAS detector at CERN was being built. This detector subsequently discovered evidence for the Higgs boson in 2012.

Transcript: Video 1 Building the ATLAS detector.

Einstein’s most famous equation and in fact arguably the most famous equation in history tells us that mass (m) and energy (E) are interchangeable via , where c is the speed of light, 3.00 × 108 m s–1. The energies involved are usually expressed in terms of a unit called the electronvolt. As a result, it’s also convenient to refer to the masses of subatomic particles in terms of their energy equivalence. For instance, the mass of an electron is about 9.1 × 10–31 kg. The energy equivalent of this mass is given by Einstein’s equation:

One electronvolt is defined to be

Therefore, , over 510 thousand electronvolts, or 510 keV (kilo electronvolts). The term ‘mass energy’ is often used to refer to this energy equivalent of the mass of a particle. Similarly, the mass energy of either a proton or neutron is around 940 MeV (940 mega electronvolts or 940 million electronvolts).

As an example of the high-energy reactions that can occur inside ATLAS, when a proton with kinetic energy of several hundred MeV collides with another proton or a neutron, new hadrons, such as pions, can be created.

In such processes, some of the kinetic energy of the protons is converted into mass, via the familiar equation , and so appears in the form of new particles. As you have learned, the pions that are created come in three varieties:

- π+, with positive charge

- π− with negative charge, and

- a neutral π0 with zero charge.

Their masses are each around 140 MeV/c2, so 140 MeV of kinetic energy is required to create each pion.

There is a hadron, formed in the collisions of pions and nucleons, with charge +2e. How can a single pion combine with a single nucleon to produce nothing but this new hadron? Is it a baryon, an antibaryon or a meson?

Pions and nucleons contain only up and down quarks, so these are the only ‘raw materials’ available from which to build the new hadron. To get a charge of +2e requires three up quarks (). This hadron can be formed by the collision of π+, , with a proton, (uud), followed by the annihilation of d with . As the hadron contains three quarks (uuu), it is a baryon.

The outcome from a high-energy collision between, say, two protons is subject to quantum indeterminacy in several ways. Imagine that two protons collide with a total kinetic energy of 200 MeV. This is enough energy to make a pion and still have a little energy left over to provide kinetic energy of the products. But what exactly will the products be? In fact there are two possibilities in this case:

Each of these possibilities will occur, and there is no way of predicting which one will be the outcome of a particular reaction. The rules that must be obeyed in these reactions are:

- energy is conserved (as usual)

- electric charge is conserved (as usual)

- the number of quarks minus the number of antiquarks is conserved.

Now look at each of these rules in more detail.

First, look at the conservation of energy, which the rules say must be conserved. There is 200 MeV of available kinetic energy, and 140 MeV is used up in creating the pion in each case. This leaves 60 MeV for kinetic energy of the products. It’s not possible that two pions can be created as that would require at least 2 × 140 MeV = 280 MeV of kinetic energy from the reactants.

The second rule is that electric charge is conserved. In the two proton reactions, the net electric charge of the reactants is twice that of a proton in each case. The net electric charge of the products in the two cases is also twice that of a proton, so electric charge is conserved in both cases.

Finally, the third rule says that the number of quarks minus the number of antiquarks is conserved. In the two proton reactions, the reactants are composed of 3 quarks for each proton and no antiquarks, so the number of quarks minus the number of antiquarks is 6 for the reactants. In the products, the number of quarks is 3 for each proton or neutron and 1 for each pion, while the number of antiquarks is 1 for each pion. The number of quarks minus the number of antiquarks in the products is therefore (3 + 3 + 1 − 1) = 6.

Therefore, all three rules are indeed obeyed in both reactions.

Imagine that two neutrons collide with a combined kinetic energy of 300 MeV. Write down all six possible reactions for producing pions that may occur.

When two neutrons collide with a combined kinetic energy of 300 MeV, this is enough energy to make two pions (with mass energy 140 MeV each). In addition, all the possible reactions to make only one pion can also occur.

In all cases, electric charge must be conserved. As the charge of the two original neutrons is zero, the net charge of the products must also be zero. The total range of possibilities is as follows:

The total electric charge on both sides of each reaction listed is zero.

In conclusion, just as electrons, protons and neutrons simplify the elements to their essentials, so a new layer of apparent complexity can be understood by the quark model. However, there is a crucial difference. If an atom is hit hard enough, electrons come out. If a nucleus is hit hard enough, nucleons come out. But if a nucleon is hit hard with another nucleon, quarks do not come out. Instead the kinetic energy is converted into the mass of new hadrons.

Activity 2 Run your own particle accelerator

This is an interactive ‘clicker’ game hosted by CERN in which you can run your own particle accelerator laboratory. It was written by four summer students working at CERN, over the course of a 48-hour hackathon. Click on the following link to launch the game; you may wish to launch it in a new window using ctrl+click.

CERN particle accelerator laboratory ‘clicker’ game [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

Start your experiment by repeatedly ‘clicking’ within the particle accelerator to register particle reactions. As you collect more data, research discoveries will appear on the left-hand side under the ‘Research’ tab, which you can unlock and read about. As you make more discoveries, so the reputation of your laboratory will increase, and the funding for your lab will grow too. As you gain funding, from the ‘HR’ tab you can hire Masters students, PhD students, Postdocs and other more senior staff who will automatically produce data, without the need for you to click. From the ‘Upgrades’ tab, you can also buy improvements to the equipment and extra support for your staff, which will increase their productivity.

Once you have things running smoothly at your lab, you can leave things running in the background and check back occasionally to see how the research is going. How long does it take you to discover the Higgs boson?

In order to understand how and why high-energy particle reactions occur, you will now examine the fundamental interaction that is responsible for how quarks behave, known as the strong interaction.