Many different plants and materials have been used to make paper and ink over the centuries. What would our scientists use from the island to make theirs and would they be able to produce a clean sheet and coloured inks in just three days?

This challenge was part of the second series of Rough Science.

Firstly, paper

What is paper and how is it made?

Paper is made from cellulose. All plant matter is composed in part of cellulose fibre but the amount varies between plants. The reason why plant material is so suitable for making paper lies in the molecular structure of cellulose and water.

Water molecules are made up of one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms. The hydrogen atom on one molecule can chain onto the oxygen atom of another molecule causing an effect called 'surface tension'. This chaining process is the key to making paper.

How do these two molecules interact?

When cellulose is suspended in water, the water molecules do not discriminate against the cellulose molecules and include them in the chain. This creates a mass of watery cellulose.

Papermakers catch this mass of watery cellulose in a screen, allow the excess water to drain off and press the soggy cellulose, which is now called 'waterleaf' paper, flat. As the rest of the water evaporates out of the 'paper', the chain effect transfers to the cellulose alone and the cellulose takes on a solid form.

How is the plant material prepared for paper making?

Plant fibres are separated either mechanically by pounding the plant material or chemically by soaking the plant material in a chemical bath. In practice, a combination of mechanical and chemical pulping is often used.

Mechanical Pulping

Plant material or wood chips are ground up and mixed with hot water and steam. The heat softens the lignin. Grinding pulls the fibres apart. This damages the fibres and makes them shorter and weaker, so paper made this way is not strong.

Mechanical pulping does not remove parts of the plant which are not cellulose or impurities and so this method is used instead for newspaper and telephone directories.

Chemical Pulping

The chemical pulping process was discovered in the nineteenth century which allowed wood to be pulped for strong, white, long-lasting paper. The goal of chemical pulping is to remove all the parts of wood which are not cellulose. Chief among these is lignin, a carbohydrate that cements adjacent cells together in wood. This material can be made more soluble by cooking the pulp either in a strong acid or a strong base.

Originally, wood pulp was cooked in lye alone but this produced a rather weak paper. The addition of sodium sulfide to the pulp produced a much stronger paper. This process is called the kraft process from the German word for strong.

Originally, wood pulp was cooked in lye alone but this produced a rather weak paper. The addition of sodium sulfide to the pulp produced a much stronger paper. This process is called the kraft process from the German word for strong.

About 80 per cent of this kraft pulp is wood and the remaining 20 per cent is lye and sodium sulfide. The pulp is cooked, or digested, at 170°C for 3 hours until most of the lignin is broken down. The liquid is drained off and the pulp is washed to remove the chemicals.

The resulting pulp is dark brown in colour. If it is made directly into paper, the resulting paper is strong but brown. This is the kind of paper out of which grocery bags and corrugated cardboard is made. For white paper, the pulp is bleached.

How did our Rough Scientists make paper?

They made our paper from kapok fibre and milkweed. The fibres were first separated from the rest of the plant. They were then beaten into a pulp and soaked in potassium hydroxide, which was made by combining lime and potassium carbonate.

Boiling the cellulose in the potassium hydroxide broke down the fibres allowing them to interweave to make paper. Once the fibres had been washed they were then sized (coated) with sticky cherry liquid. This would prevent the ink soaking in like blotting paper.

Our scientists made a paper press to squeeze out excess moisture before leaving the sheet to dry in the sun. They ended up with a strong piece of pale paper.

Now for the ink and pens.

How is ink made?

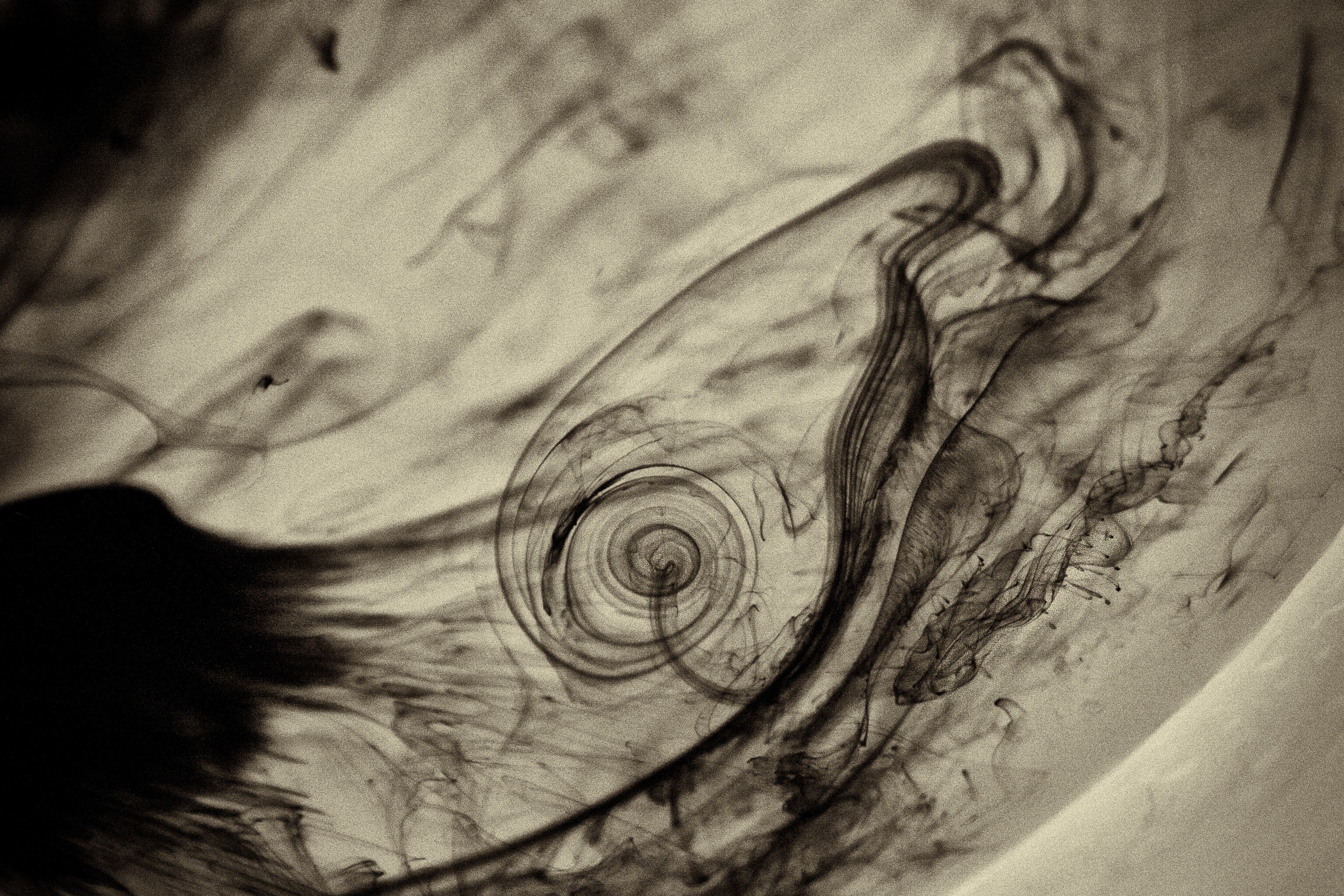

The ink made by our scientists was created by the chemical reaction between tannic acid and iron sulfate in an aqueous solution. The primary active components in tannin are gallotannic and gallic acid. With iron (II) sulfate, these tannic acids produce a black pigment upon exposure to oxygen.

A small amount of pigment forms by reacting with oxygen in the water but much more pigment is produced after the ink has been applied to paper and exposed to air for several hours. The team also used a small amount of sticky cherry juice as a thickening agent and binder.

How were the different hues achieved?

To colour the dyes, the scientists used logwood, indigo, mango and tea. The plants were boiled in tap water and acids and bases were added to change the colours. For example, logwood creates a blood red solution, although it will change to blue in alkaline solutions and to yellow-orange in highly acidic solutions.

Finally, the scientists used a range of coloured inks on our Rough Science paper. They made brushes out of Ellen's hair and used Acacia seed pods as ink pens.

Find out more

Paper

Handmade Paper - from the Exploratorium site

Papermaking - from the Eduscapes site

The Prairie Paper Project - University of Iowa Computer Science site

Have a go yourself (although perhaps starting with paper in the first place is cheating...?)

Ink

Ink & pigment recipes - from the Travelling Scriptotium

Have a go yourself:

Books

- Papermaking with plants: creative recipes and projects using herbs, flowers, grasses, and leaves by Helen Hiebert, Storey Publishing 1998; ISBN: 1580170870

- Handmade Paper by Maureen Richardson , Apple Press 1999; ISBN: 1840922257

- Making paper by hand by John Sweetman, pub Wells, Somerset : Wookey Hole Caves Ltd.1977

- Dyer's Garden: From Plant to Pot: Growing Dyes for Natural Fibers by Rita Buchanan, pub Interweave Press 1995 ; ISBN: 1883010071

- Nature of the Islands: Plants and Animals of the Eastern Caribbean by Virginia Barlow, Cruising Guide Publications 1993; ISBN: 0944428134

- General information about tropical plants and their uses: Tropical Forests and Their Crops by Nigel J.H. Smith, J.T. Williams, Donald L. Plucknett and Jennifer P. Talbot, pub Cornell University Press 1992; ISBN: 0801427711(Discusses general groupings of useful plants)

- Botany for Gardeners: An Introduction and Guide by Brian Capon, B.T. Batsford 1992; ISBN: 0713472529 (A good general text on how plants function)

- A Field Guide to the Families and Genera of Woody Plants of Northwest South America: (Colombia, Ecuador, Peru): With Supplementary Notes) by Alwyn H. Gentry and Adrian B. Forsyth, University of Chicago Press1996; ISBN: 0226289443 (An excellent resource on learning to identify tropical plants in the field/forest)

- Encyclopedia of Common Natural Ingredients Used in Food, Drugs, and Cosmetics by Albert Y. Leung and Steven Foster. 1995 John Wiley & Sons Inc; ISBN: 0471508268

- Fruits and Vegetables of the Caribbean by M.J.Bourne, G.W. Lennox, and S.A. Seddon, Caribbean Publishing 1988, ISBN: 0333453115

- Trees of the Caribbean by S.A. Seddon, Caribbean Publishing 1980 ; ISBN: 0333287932

- Nature of the Islands: Plants and Animals of the Eastern Caribbean by Virginia Barlow, Cruising Guide Publications 1993; ISBN: 0944428134 This book has all the plants used by the Rough Science team, plus information about the ecology of the area.

A couple of children's books

- The Great Kapok Tree: A Tale of the Amazon Rain Forest by Lynn Cherry, pub 2000 Voyager Books; ISBN: 0152026142

- El Gran Capoquero: UN Cuento De LA Selva Amazonica by Lynn Cherry, translated by Alma Ada, 1994 Harcourt; ISBN: 0152323201

This page was updated in April 2017 to remove some dead links, include the video tutorials, and to redraft the text to make better sense outside of the context of the original programmes.

Rate and Review

Rate this video

Review this video

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Video reviews