Find out more about The Open University's Science qualifications.

AstrobiologyOU aspires to understand how, and where, life might be found and to address the scientific and ethical challenges faced by astrobiology-related exploration missions. In November 2021, we hosted a series of three conversations – The Borders of Astrobiology – to explore some of the ethical challenges that stretch astrobiology beyond its scientific origins.

The first conversation – (un)disciplined futures – discussed ethical questions in space exploration. The second – inclusion, fairness and engagement – considered issues of ethical engagement and knowledge production in astrobiology and the third – astroenvironmentalism – examined extending concepts of the environment and environmental ethics to outer space. The conversations ranged across a wide variety of themes. In this article, three of the speakers offer further thoughts on some of the questions and ideas we discussed.

How far away do you think we are from showing the space environment humility and respect? Should we be confident/positive about the future of space governance?

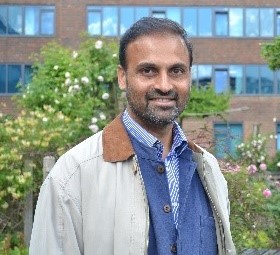

Andrea Owe, environmental philosopher

with the Global Catastrophic Risk Institute:

Andrea Owe, environmental philosopher

with the Global Catastrophic Risk Institute:

The short answer is, quite far. It depends, of course, on who you ask – who is ‘we’? In the end, however, what matters in practice are the attitudes of those in decision-making positions, and of those who will actually go to space. I am not positive about the future of space governance at the moment, because the specific people in power right now hold, in my view, the wrong attitudes and ideas about what is good, what is valuable, and what are humans-in-nature – evident in the present global state of socio-environmental crisis. They represent a culture of exploitative, entitled and subjugating attitudes toward the rest of nature, and now also space. I’ve seen estimates of entire foreign planets’ worth in dollars. That horrifies me. But we can – and should – work to diversify and democratise the decision-making process in space governance.

I think one major obstacle to having respect for the space environment is the fact that it appears lifeless. Many humans have a strong life-bias and therefore find it hard to care for an environment in which there is no life. However, this is also a question of which peoples’ views are considered. A variety of Indigenous and environmental perspectives have respect and humility toward abiotic nature, typically as part of a holistic moral worldview that respects the wider ecosystem in which the abiotic elements of nature are interlinked with the biotic. These views often include the space environment, for example considering extra-terrestrial places such as the Moon part of kinship relations to humans and other nature on Earth, and recognising that other planets and celestial places have their own integrity, story and inherent rights as places of nature and creativity. Including these perspectives in a diversification and democratisation of space governance can, therefore, be helpful toward building respect for places in space.

There are essentially two things that concern me if we approach space without reverence. The first is ignorance: we do not know what these foreign worlds may hold. Not just potential life, but also other forms of value we do not know or recognise. On our own planet, we have a long way to go in discovering and appreciating the many forms of value it holds or might come to hold. Looking at another planet – an entire, giant, billions of years old planet – and claiming that it is completely valueless (or only has economic value) is, in my opinion, weird, exceptionally narrow-minded, and arrogant to the extent of being silly. We are human and we see things from a human perspective, but we are perfectly capable of understanding that things can exist without relation to us, just as Earth existed for billions of years before we came along, with all kinds of complex things going on. Such a narrow view also ignores not only existing moral diversity among present humans, but the fact that human morality itself changes over time. Going into space in any extensive way is a multigenerational endeavour, and so only considering what a few people currently think inherently risks missing important insights yet to be had, and thus risks causing irreversible harm.

Launch of NASA Mars2020 Perseverance Rover mission. (NASA/Joel Kowsky 2020)

The second concern is the longer-term, practical consequences of entitled and exploitative attitudes. We know now these attitudes have played an important part in bringing about a global state of unsustainability on Earth. It is not that humans are not entitled to use other parts of nature, just like all other members of the Earth ecosystem are, but sustainability is about taking and giving back in a manner that lets the system continue, so that it can, among other things, keep sustaining you. The problem is not entitlement as such, but a perceived human entitlement of everything, always. That is the part that is not compatible with the reality of nature, and the same natural laws apply across the universe. I worry that starting out in space with the same attitudes that have proven pragmatically problematic on Earth will set us up for recreating the same flawed systems that also harm and threaten ourselves. If the goal is to eventually sustain civilisation and life across deep time by spreading in space, then we need to get really good at living sustainably wherever we are. If the first three generations on Mars completely drain Mars and its surrounding space environment of resources, that’s arguably a pretty massive failure on behalf of the generations to come.

I will be positive about the future of space governance once its objective is to further fundamental public values across generations (and species), and to obtain sustainability – not ownership and exploitation – on a multiplanetary scale.

If we want to open astrobiology research to all communities, how do we address the problem of scale? It’s possible to imagine an engaged project that works beautifully with a small, single, engaged community that stays with the project from start to end. What issues will we need to address when we scale up engaged research to regional or national scales? Should we even try? Is quantity less important than quality?

Richard Holliman, Professor of

Engaged Research at the Open University:

Richard Holliman, Professor of

Engaged Research at the Open University:

First and foremost, I wouldn’t define the issue of scale as a ‘problem’ (I’ll come back to this). The bigger question that sits behind this, about who is involved, why and how, is really well-made though.

In some ways it’s reasonable to argue that engaged research was developed in response to the idea that engagement was all-too-often more concerned about ‘reach’ than ‘significance’. Engaged research design doesn’t start with numbers of people engaged as a target. Rather, it is built on the premise that the seven dimensions – preparedness, politics, people, purposes, processes, participation, performance – should be considered in relation to each other; changing one dimension requires some consideration of the potential implications for the others. There’s more information in this pamphlet on designing public-centric research.

Starting with the purpose of the engaged research in relation to who could and should be involved is key. Thinking about who could and should be involved requires consideration of issues of representation, utility and emergence (as described in this case study). It could be, therefore, that numbers for an engaged research project, notwithstanding the obvious resource implications, could be quite sizeable, and could well involve representation across constituencies, regions, nations, etc.

Then there’s the question of processes, and when these are deployed within the research cycle. Put simply, an argument could be made to engage in a local context with a smaller group of stakeholders, but with the express intent to engage with wider constituencies later in the research cycle. This could involve representation across constituencies, regions, nations, etc.

Engagement later in the research cycle could be to validate the outcomes of the earlier engagement. Alternatively, it could be to adapt the outcomes of the earlier engagement to that new context. In both instances, it would be important for all stakeholders to sign up at the start of their engagement to the principles of sharing: if you’re looking to share and accept that adaptation is a valid and useful objective, outcomes should not be fixed in time and space.

This brings me back to the question of whether engaging at scale is a ‘problem’. I don’t see scale as the problem. The key question is why is scale the solution? If you can answer this question then you’ll need to address the most difficult of challenges, identifying funding that allows people to engage meaningfully at scale. Good luck.

Does drawing on anthropology to underpin our research mean that we will be more inclined to look for the same, for what we know on Earth, on other planets and might perhaps miss the novel?

Shonil Bhagwat, Professor of Environment and Development at The Open

University:

Shonil Bhagwat, Professor of Environment and Development at The Open

University:We, as humans, come with a certain cognitive machinery and we cannot deny that our view of life has a particular anthropocentric bias. I would say that the search for intelligent life beyond Earth has that anthropocentric bias – we are essentially looking for extra-terrestrial intelligent life that is like ourselves. However, astrobiology is interested in life more broadly defined. This includes unicellular organisms, microbes, or simply chemical signs (complex molecules, proteins, or other structures that are the building blocks of life) that life might exist beyond Earth.

Arguably, some of this life may well be ‘intelligent’ in the sense that microorganisms have much more influence on shaping their habitat than we would like to think, even though this form of intelligence does fit well with the anthropocentric norms of intelligence. So, in answer to the question, I would say that astrobiology is in some sense agnostic to what life on other planets might look like and is more accepting of the novel, as opposed to the scholarly field that is looking for intelligent life in a conventional sense.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

At the borders of knowledge, we have the opportunity to construct progressive approaches to change, by drawing on what we know has been done in the past, what we believe to be possible now and what we imagine could be in the future. If you have enjoyed these perspectives, you can watch the original conversations on the Open University’s Faculty of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics YouTube channel:

This article is part of the Astrobiology Collection on OpenLearn. This collection of free articles, interactives, videos and courses provides insights into research that investigates the possibilities of life beyond the Earth and the ethical and governance implications of this.

This article is part of the Astrobiology Collection on OpenLearn. This collection of free articles, interactives, videos and courses provides insights into research that investigates the possibilities of life beyond the Earth and the ethical and governance implications of this.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews