Glasgow and COP26

After a delay, due to the COVID pandemic, COP26 finally went ahead in Glasgow, meaning there has been considerable international attention on the city. In recent decades Glasgow has been portrayed as an example of a city that has undergone a successful ‘transformation’ from an industrial hub to a vibrant ‘post-industrial’ centre. The complex, uneven, conflicting and ever-changing entanglements of Glasgow’s social and economic needs with matters of environmental health and wellbeing are evident throughout Glasgow’s history, even if rarely acknowledged or understood much of the time. As Glaswegians, this is an important time to reflect on this history.

Glasgow: from the second city of the Empire to….?

Glasgow has long had a ‘global footprint’, being a key player in the UK’s industrial revolution, the so-called ‘second city of the Empire’. Glasgow was particularly famous for shipbuilding, locomotive manufacture, engineering and carpet works. These

industrial processes had direct environmental and health impacts on a densely populated and growing urban landscape.

To provide a workforce, people migrated, particularly from the Scottish Highlands and Ireland, thereby contributing to urban growth and development, and the consequent overcrowding and slum housing conditions for which the city became notorious. It was not until the latter half of the 20th century that the city began to be changed by the introduction of 29 ‘Comprehensive Development Areas’ with an objective of clearing slum dwellings (Glasgow Today and Tomorrow | Scotland on Screen). Through the development of new housing estates situated at the edge of the city such as Easterhouse, Drumchapel, Castlemilk and Pollok, much of the population has been relocated from the city centre to these areas (TheGlasgowStory: 1950s to The Present Day: Neighbourhoods).

Glasgow: the dear green place

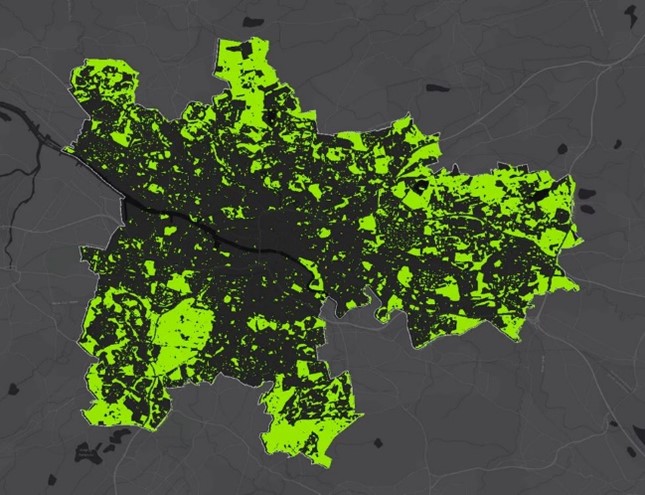

The historic presence of heavy industries belies that Glasgow is also known as the ‘dear green place’. The city has significant parkland (glasgow.gov.uk) within its boundaries, as can be seen on this map.

Glasgow has over 90 parks, including Pollok, Alexandria, Kelvingrove and Springburn Parks to the south, east, west and north respectively.

Glasgow environmental and social issues

However, pull aside the branches and it is not long before problems with the city’s environmental landscape become apparent. Walking through the streets, you will see many are covered with graffiti, litter, fly-tipping, dog excrement, vandalism and weed growth. For 17 years, the charity ‘Keep Scotland Beautiful’ has monitored these environmental degradation indicators, and reported in 2020 that the poorest areas demonstrated the highest levels of each (keepscotlandbeautiful.org). Evidence of extensive graffiti and litter pile-up can be seen less than a mile from the Glasgow COP26 site.

Glasgow has deep-rooted issues of poverty, disadvantage and deprivation (www.gov.scot). Over 25% of Glasgow’s population lives in areas registered in the lowest 10% in the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD).

In contrast, just over 5% of the Glasgow population live in the highest 10% (gcph.co.uk). Inequality means an unequal distribution of social resources including income, wealth, education, health and environmental

surroundings. The poorest areas have experienced a more severe and faster rate of decline in local environmental quality than less deprived areas, with the gap between the indicators of litter, fly-tipping and graffiti widening between the poorest

and most affluent (keepscotlandbeautiful.org).

Thus, there is a social justice element to local environmental degradation. People already living at the lower end of the inequality spectrum are also relatively more exposed to the consequences of poor-quality neighbourhood environments than their more affluent counterparts. High existing levels of litter, graffiti and vandalism in an area might lead to increased levels of antisocial behaviour, a link known as the ‘broken window’ theory (Coghlan, 2008) – though this theory has been seriously contested (Northeastern University, 2019). There is evidence that local environmental quality has a significant impact on life satisfaction (keepscotlandbeautiful).

UK and Scottish Government ‘Austerity’ policies have only served to contribute to further deterioration in the quality of Glasgow’s environment. Funding cuts to local authorities, such as Glasgow City Council (GCC), disproportionately hit the poorest in society, as they rely more on the services the Council provides (Glasgow University, Policy Scotland).

Glasgow: towards improvement?

However, it is not all doom and gloom. Overall, Glasgow is less deprived than previously. In 2004, nearly half the population lived in areas classified in the lowest 10% of the SIMD, compared to 28% in 2020 (gchp.co.uk). And despite cuts, the Council’s environmental services do clean graffiti once reported; there are regular waste and bulk waste uplifts, which are continually under review for cost and service efficacy purposes. There are teams of Neighbourhood Improvement Volunteers (NIVs) who go on litter picks, supported by GCC’s Neighbourhood Improvement and Enforcement Services (NIES) (Glasgow.gov.uk).

Glasgow has its 90 parks, 90 community gardens, 3 market gardens and 32 allotment sites to help keep it green, contributing towards the city’s ambitious carbon neutrality objective for 2030 (sustainableglasgow.org.uk). Most importantly though, the leaders of GCC, all from the Scottish National Party (SNP), recognise that any environmental sustainability measures must include combatting social injustice.

The COP26 conference put Glasgow centre stage for a few weeks. Glasgow’s cleaner face was presented, which has its merits in promoting the city. Nevertheless, it is important to recognise Glasgow’s environmental and social imperfections, in order to keep improving in these areas on political and action agendas.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews