2.4 Integrated Cognitive Antisocial Potential theory

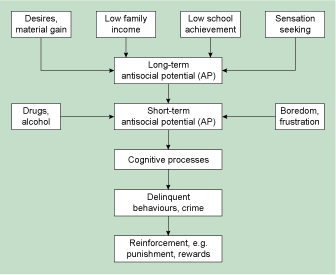

Using the findings from the Cambridge study, Farrington alone (1995; 2003; 2005) and in collaboration with colleagues (2006) was able to develop a theoretical model looking at the risk factors for crime called the Integrated Cognitive Antisocial Potential (ICAP) theory. The ICAP theory was designed to try and explain the offending behaviour of males from working-class families. The main concept is a person’s antisocial potential (AP), which is their potential to commit antisocial acts and their decisions to turn that potential into the reality of committing crime. Whether the AP is turned into antisocial behaviour depends on the person’s cognitive processes that consider opportunities and victims.

According to the ICAP theory, individuals can be placed on a continuum, from ‘low’ to ‘high’ AP, and although few people have a high AP, those who do are more likely to commit crimes. The primary factors that influence high AP are:

- desires for material gain

- status among peers

- excitement and sexual satisfaction.

However, whether these issues influence behaviour will depend on whether the individual can use legitimate means to satisfy them. For example, people from low incomes, the unemployed and those who are not successful at school may be more likely to engage in antisocial behaviour. This theory therefore suggests that males from low-income families with low school attainment and who are unemployed are more likely to commit crimes to achieve material gain (for example, the latest mobile phone), as compared to others from different backgrounds.

The ICAP theory also suggests that there are long-term and short-term factors for AP. Individuals with long-term AP tend to come from poorer families, be poorly socialised, impulsive, sensation seeking and have a lower IQ. For example, children who are neglected or receive little warmth from their parents may care less about parental punishment and therefore do not learn to avoid behaving in antisocial ways. Individuals with short-term AP may not necessarily have been affected by these issues, but may temporarily increase their AP by situational factors, such as frustration, anger, boredom or alcohol. These situational factors may influence a person to make decisions about their behaviour that they may not make in other situations. Furthermore, short-term AP can develop into long-term AP depending on the consequences of antisocial behaviour or offending. If the consequence for offending is material gain, status and approval from peers, it is likely to be repeated. However, it may be a different matter if the behaviour leads to disapproval or imprisonment.

The ICAP theory also looks at factors that might prevent an individual from offending, and these can be social and individual reasons. For example, as a person gets older they tend to become less frustrated and impulsive. There may be important life events that reduce AP, such as marriage, steady employment or moving to a new area, which can shift interaction with peers to girlfriends, wives and children. Farrington (2003) suggests that these life events can have a number of influences to reduce AP. They can:

- decrease offending opportunities, by shifting routine activities such as drinking with male peers

- increase informal controls of family and work responsibilities – spending time with family or working may become more important than socialising with peers

- change decision making by reducing the subjective rewards of offending because the risks of being caught are higher than they previously were, for example disapproval from partner, threat of incarceration and leaving the family.

Farrington (2003) believed that as this theory established a number of risk factors for offending, it would be possible to develop some interventions to prevent those identified as most at risk from offending. For example, cognitive–behavioural skill training to help reduce impulsive behaviour, and parental education to help promote good child-rearing practices and improve parental supervision.