1 The aspects and meanings of citizenship

The issues discussed in this course are considered in relation to different aspects and meanings of citizenship: people's legal and political status, their rights, opportunities to work, access to welfare, sense of identity and belonging, and practices of the everyday.

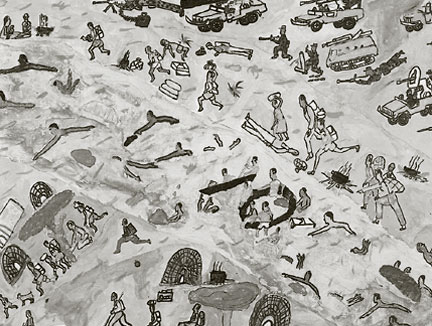

Throughout human history people have migrated from their place of birth for different reasons – for example, to seek new ways of surviving, to colonise new lands, to establish new markets for trade, or because they feared for their lives in their country of origin. Large movements of refugees around the world, as in the late twentieth century, are often linked to wider regional or global struggles, as illustrated in Figure 1. People flee mainly because of war, repression and human rights abuses rather than poverty (Crawley and Loughna, 2003). However, the distinction between being a ‘refugee’ or an ‘economic migrant’ is neither simple nor straightforward.

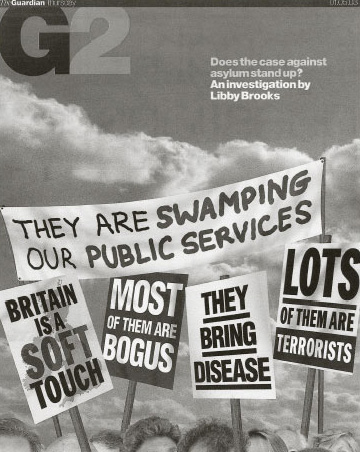

To explore some of the reasons why people have sought refuge in the UK in particular, we are using the personal stories of four individuals, placing the interpretation of these accounts in the social policy context of two particular historical moments – the decade following 1933 and the period between 1991 and 2003. During this latter period ‘asylum’ was constructed by successive UK governments as a ‘political crisis’ in the context of a ‘crisis’ of the UK welfare state, a drive towards a common European asylum policy (Bloch and Schuster, 2002) and a claim that the forces of globalisation are irresistible. Dominant official and media discourses assumed that increasing numbers of people were seeking asylum in the UK because of the generous welfare benefits available, that the ‘welfare state’ could not afford this, that the UK was already overcrowded, that there were not enough jobs and that the presence of so many ‘aliens’ or foreigners was a threat to ‘community’, ‘national identity’ and ‘our’ way of life. Figure 2 shows some typical headlines from UK newspapers in the early 2000s, in which ‘asylum seekers’ are clearly constituted as one of the most demonised groups of people in the UK media.

The sets of interconnections between citizenship, personal lives and social policy can be thought about in the following way.

First, refugee and asylum policy and practice raise important questions about the nature of citizenship in relation to the rights and sense of belonging that citizenship as a status conveys. For example:

-

Should citizenship be based upon place of birth, parental nationality, place of residence, or simply human value and dignity, regardless of these issues?

-

Should globalisation mean that rights of citizenship can no longer simply be tied to birth in a specific nation-state?

Second, the mutual constitution of personal lives and social policy comes into stark focus for the person who flees one country and has to negotiate entry to a life in a new country (each of the countries having its own particular social, economic, political and cultural forms). The personal accounts that follow in Section 2 illustrate these connections well.

Third, exploring these interconnections illuminates the relationship between citizenship as a set of rights and claims, on the one hand, and as cultural or national identity on the other.

The primary theoretical perspective through which these issues are explored in this course is post-structuralism, because of its emphasis on the production of social meaning and the effects of such meaning or ‘knowledges’ on the experiences of different social constituencies. Post-structuralism is also used because this emphasis on meaning systems – or discourses – allows us to think about alternative or counter discourses through which opposition to dominant policy discourses may be presented. Forms of feminist and postcolonial theory will also be drawn on. Feminism alerts us to the impact of gender on the experiences of refugees and asylum seekers and how discourses of gender run through relevant policy. Postcolonial theory draws attention to questions of ‘nation’, its peopling, and national identity in colonial and neo-colonial configurations of power. It helps us to consider links between contemporary government approaches to refugees and asylum seekers and the generalised anxieties over multiculturalism and cultural identity prevailing in the UK in the early twenty-first century. The nature of the evidence used in our explorations is a theme running through the rest of the course.