Sustainable Innovation Support services

The overall aim of AgriLink was to stimulate transitions towards more sustainable European agriculture through better understanding the roles played by a wide range of advisory organisations in farmer decision-making, and by enhancing their contribution to learning and innovation. We think it is helpful to delve a little into the research in this area to better understand this context and how it impacts on the work of the Living Labs.

The sustainable development of agriculture is a longstanding European Commission policy principle (see Council Regulation (EC) No 1257/1999, Marsden, 2003). Farmers are faced with contradictory challenges, such as reducing emissions and input use, increasing animal welfare, producing environmental goods, enhancing social cohesion in rural areas, as well as securing their traditional roles in food and fibre production, and securing income in a period characterised by prices volatility and economic uncertainties.

The notion of sustainable agriculture particularly gained prominence through the Brundtland Report (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987), ‘Our Common Future’, where sustainable development was defined as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’. It is widely agreed in academic and policy communities that increasing the sustainability of agricultural systems is a necessary and important objective.

However, the definition of sustainable agriculture is complex and contested (Robinson, 2008; Velten, 2015) and is complicated by the recognition that actions or technologies can contribute to sustainability in some contexts but not others. It is also complicated by how people view technology. Many might just see this as mechanical, electronic, chemical or other physical artefacts, but in AgriLink we took a wider perspective of technology as methods, systems and devices, which are the result of scientific knowledge being used for practical purposes.

Some of these distinctions are discussed further in a Practice Abstract by Boelie Elzen of Wageningen Research as reproduced in Box 2.1 on sustainable development in agriculture.

Box 2.1 Sustainable development in agriculture

AgriLink Practice Abstract 17: Sustainable development in agriculture [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

| As a state of affairs: a specific agricultural technology or practice can be more or less sustainable. |

| As a process of ‘sustainable development’: developing more sustainable agricultural technologies and practices. |

Both are important, the first to assess where new development is needed and the second to take action to change unsustainable practices.

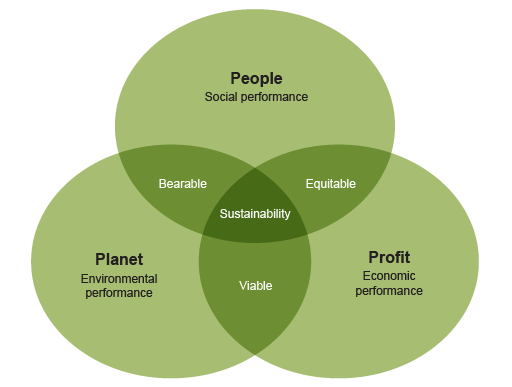

Three different dimensions (or pillars) of sustainability are distinguished, the triple P model: people (social sustainability), planet (environmental sustainability) and profit (economic sustainability). Sustainable development aims to balance the three pillars such that all can be maintained simultaneously in the long term. The practical implication is that it is not very productive to state where something is sustainable or not.

For a concrete case, one needs to identify the specific sustainability issues that are at stake for each of the three Ps and assess which of these is most problematic (i.e. least sustainable). Sustainable development should then develop new solutions for that dimension, without making things worse in the other dimensions.

However, with a poor performance in one of the dimensions (e.g. large emissions of greenhouse gases), a slight decrease in one of the other dimensions (e.g. slight loss of income) may be considered acceptable if the poorly performing dimension is considerably improved.

Hence, most of all, sustainable development is a balancing act towards achieving ‘integral sustainability’, i.e. sustainability on all relevant dimensions.

More information on this topic can be found in this AgriLink Theory Primer on Sustainable Development.

The notion of balancing or re-balancing between these three dimensions is often represented visually as in Figure 2.2. Focusing effort on just two dimensions produces some benefits (which I don’t talk about any further), but sustainability requires attention to all three dimensions.

Transitions towards sustainable development thus imply the need to support innovations that integrate different dimensions. This situation is associated with the increasing complexity and uncertainty associated with innovations. As a result, there is a need to combine different types and sources of knowledge in agriculture: disciplinary and interdisciplinary academic knowledge, evidence from experiments (applied research), farmers’ local and lay knowledge, and knowledge carried by emerging stakeholder in agricultural debates (consumers’ groups, environmental associations, etc.), but also by actors developing technologies outside agriculture (e.g. ICT companies supporting the development of data-driven agriculture).

Agricultural advisory services across Europe are also changing: widespread privatisation of advisory services (Labarthe 2009, Sutherland et al., 2013), fragmentation (Garforth et al., 2003), new businesses entering the sector (ranging from local consultancies to transnational companies), and reduced access to advice in situations where service provision is less commercially viable (Labarthe and Laurent, 2013). As a result, current AKIS are characterised by a plethora of service provision models and of new forms of partnerships (public-private, etc.). This has led to several new challenges facing agricultural advisory services in terms of how innovation is fostered and managed in order to meet the goal of sustainability.

To tackle these challenges adequately, new approaches to advisory service provision are needed, in order to connect research and farmer-based interactive innovations with advisory services and to boost innovation co-creation. The setting up of six Living Labs in AgriLink was done specifically to develop and test new advisory methods and tools to better link research and practice, and to both provide insights in the collective learning involved and to evaluate the Living Lab approach as an innovation process.

We will look at these six Living labs in more detail in Session 3. For now, I want to look at the relationships between three key aspects of innovation support services in agriculture: innovations, practices, and knowledge generation and exchange.

Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems (AKIS)