Design thinking

Reflective Activity 8

Reflective Activity 8

Make notes below on what you think are the main features of design from your knowledge and experience.

The answer you give will depend upon your own knowledge and experiences but equally I have talked about design in certain ways during the course that might influence you. But the main aim of the activity is to get you thinking about a very common process – design – and what makes it useful before I talk about design thinking.

Answer

Designs are the things that design thinking produces – the products of thinking if you like. Almost everything you see around you is designed; that is, it exists as a result of human thought about what is needed. As I sit in my office, I see a telephone, a cup, a building opposite my window, a computer in front of me, the chair I am sitting on and the clothes I am wearing. These are the obvious objects of design.

However, there are less obvious things, too: the software I am using to write this paragraph, the circuit boards in the computer (and the chips on the circuit board), and the way I have organised the sections of this course and gone about using different elements of AgriLink work. So, design involves processes, systems and structures as well as products.

If you ask most people what they think design is, they will probably mention something like the iPhone, something that looks a bit different from other things in the same category and that probably claims to outperform them as well. This is what I call ‘designer design’: things that are produced to showcase design, and which are marketed and written about accordingly. They are things that have been ‘given’ to us by designers, rather than being something we participate in.

Yet there is another side to design that I will call ‘practitioner design’. By this I mean the kind of design that you or I might do to our personal space, or the things that are designed but go unnoticed, such as road markings. Practitioner design is much more prevalent than designer design and impacts almost every aspect of our lives. That is not to say that practitioner design is not designed by professionals, most of the time it is, but sometimes it is not referred to explicitly as design.

We might better describe practitioner design as being the products of everyday design thinking and practices – the processes, systems and structures – that meet our needs and shape our everyday behaviours.

Lawrence Lessig has noticed how designs (he calls them ‘things’) often have a ‘law-like’ character, regulating our behaviour in certain ways. Lessig (1999) describes four ways in which our behaviour is controlled and regulated.

Let us look at the example of parking:

| The first is by the law. It is determined that it is illegal to park in some places, and most people generally observe this law. If they break this law, and are observed to have done so, they are penalised. |

| The second is by norms. In places where people do park, they observe an unofficial code – ‘leave a bit of distance between the car you are parking next to’, or ‘do not block someone else's exit’. |

| The third is by the market. Whether you can afford to park affects your ability to park. So, if the market determines a price that you cannot afford (or refuse to pay), then you will look for somewhere else to park. |

| The final way is by architecture (what we can think of as design). A few painted lines on a piece of tarmac mean that we all park in a certain orientation, because the architecture ‘tells’ us to. |

If the product of design thinking is something that is able to improve our lives and shape our behaviour, it self-evidently originates from, and involves, people. In contrast to an activity like art, which often (though certainly not always) involves only one person in its production, design usually involves several people in several different roles. Design, then, is something that is inherently social or, put another way, something that creates social or cultural value. Of course, this value can come in a lot of different forms: ease and effectiveness of use, economic value, aesthetic value, functionality, meaningfulness – all these things and more contribute to the way in which design creates value.

Let us think about the number of people that might be involved in design. First, we have the designer themselves. For the moment we can assume that they are at the fulcrum of a design process. But perhaps there is more than one designer? The designer, or team of designers, is usually working on behalf of someone: the person we normally call the client. The client is the person or persons who have an ‘unfulfilled need’; they have a problem that needs solving and are usually prepared to pay to have it solved. The solution to their problem will often involve other groups of people. The role that these types of people play – designer, client and user – can often overlap and be the same person. Generally, however, these will be different people or groups of people.

In the past, the role of the designer was reasonably clear; the designer was the person who came up with the ideas and presented them to the client, who then chose the one they liked best. Designers also tended to stick to specific disciplines: graphic designers concentrated on graphics, architects on buildings, fashion designers on clothing, and product designers on products. In the past few years, though, a different kind of designer has emerged. This is a person or persons who can bring together expertise to tackle more complicated problems, not necessarily problems that can easily be solved by just one discipline. This is a person or persons who can ‘organise’ a solution by using several methods. These are the type of people needed at the heart of Living Lab. But equally such people who ‘facilitate’ the design process to create an innovative solution to a need or problem also need frameworks to guide their work – which is where models of design thinking come in.

In his 1969 seminal text on design methods, The Sciences of the Artificial, Nobel Prize laureate Herbert Simon (1969) outlined one of the first formal models of the design thinking process. Simon’s model consists of seven major stages, each with component stages and activities, and was largely influential in shaping some of the most widely used design thinking process models today. These seven steps are Define, Research, Ideate, Prototype, Choose, Implement and Learn.

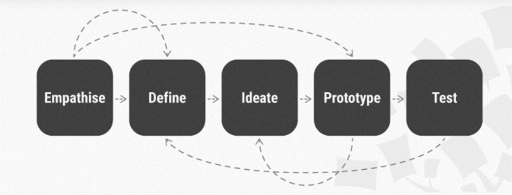

There are many variants of the design thinking process in use today, and while they may have different numbers of stages ranging from three to seven, they are all based upon the same principles featured in Simon’s 1969 model. A brief history of design thinking can be found here [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] on the Interaction Design Foundation website. In AgriLink, we used a five-stage model, Empathise, Define (the problem), Ideate, Prototype and Test, that is promoted by the Interaction Design Foundation (Figure 4.1).

Design thinking is a method for practical, creative resolution of problems. It is a form of solution-based thinking with the intent of producing a constructive future result. Design thinking is especially useful when addressing wicked problems, which are ill-defined or tricky. With ill-defined problems, both the problem and the solution are unknown at the outset of the problem-solving exercise.

The five steps of design thinking (Figure 4.1) are:

| Empathise: gain an empathic understanding of the problem through observing, engaging and empathising with people to understand their experiences and motivations |

| Define: analyse observations and define the problem in a human-centred manner |

| Ideate: generating ideas |

| Prototype: production of an inexpensive, scaled-down version of the product useful to investigate the problem solution |

| Test: the complete product using the best solutions identified during the prototyping phase. Results of the test can be used to redefine one or more problems and result in an iterative process. |

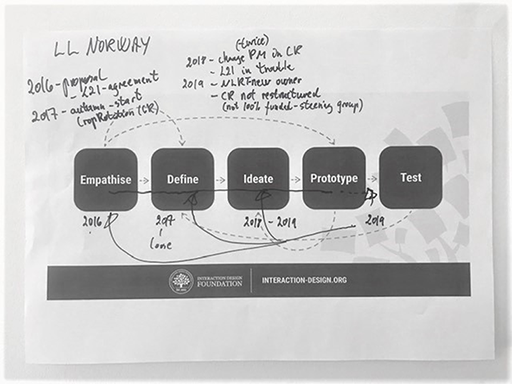

While there is a linear sequence from empathise to test, Figure 4.1 also makes clear there are feedback loops where iteration is necessary between stages as understanding and insights develop, and as can be seen in Figure 4.2 which shows a review of the steps and timings involved in the Norwegian Living Lab.

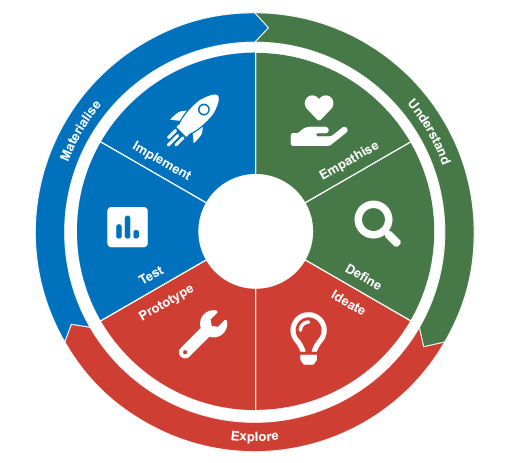

Due to this non-linearity and iteration, it can help to represent the five steps as a circular process (Figure 4.3).

In the Living Labs, we went through these five steps together with a core group of stakeholders. In each step we made use of the process tools and experiences of project partners to improve the articulation of motives and demands and to generate creative solutions and ideas. We also want to stress again that although in Figure 4.1 the approach is presented as a linear process and in Figure 4.3 a circular process, in reality it evolves in a more flexible and non-linear fashion with divergent and convergent parts to each step and iteration through the steps as a result of changes in technology or legislation as indicated in Figure 4.2.

For example, the development of a prototype can lead to an improved understanding of the problem or lead to a new brainstorming session. In reality, there are many potential obstacles to creating a good design thinking process. For example, empathy can seem simple to do, but if the need is unclear, problems can arise during prototyping, and so take time to clarify the needs – within the AgriLink Living Labs there were sessions with groups of farmers.

Choosing appropriate tools and techniques can be crucial – within AgriLink we used the GPS method for brainstorming which allows people to think individually and in a group (there is much more on the tools and techniques we used in later sessions and in the toolbox guide). Also, the intensity of co-creation, cooperation with the farmer and other stakeholders is not the same at every stage and depends on the specific context.

Indeed, important to the development of the Living Labs and scaling of lessons and experiences was to go about our processes systemically whereby we were continually contextualising what we were doing, recognising our influences and what we were affecting as we went along. The techniques (and skills) of systems thinking and in particular systems diagramming proved very helpful.

Session 4 The multi-method approach: applying design thinking and systems thinking