Open Educational Practices in Design, Production and Use

Introduction

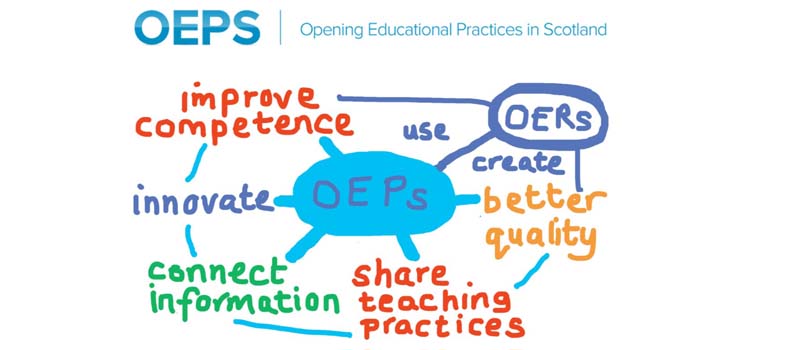

This report explores the design, production and use of Open Educational Resources (OER – openly licensed online learning materials) through three interlinked case studies. It is based on work conducted by a Scottish Funding Council (SFC) programme, Open Educational Practices in Scotland.[1]

OEPS is hosted by the Open University in Scotland, and its role is to raise awareness and capacity in educational practices that support the design, production and use of OER across the formal and informal sector in Scotland. The SFC has asked OEPS to focus on the skewed socio-economic profile of OER users.

OEPS has approached this problem as a question of educational practice, of what to do (Kemmis 2006; 2010); addressing the challenges, through applying practice based research from a range of disciplines and perspectives, to frame and reframe our understanding of the issues and also exploring the range of possible solutions. Notably we have drawn on practitioner research from Widening Participation (WP), which explores the visible and hidden barriers to engaging in education (Fuller & Paton 2008; Bathmaker et.al 2013), and how they layer and intersect (see Levitas et.al 2007), distancing people from education. Alongside questions from WP around the pedagogic assumptions made within the academy, which effect the recruitment, retention and progression of vulnerable learners, we also look at the (often tacit) assumptions around digital literacy made within open and online materials.

We approach open educational practice as a question of design, of designing learning journeys around the needs of users. We have found approaches from Design Thinking (Cross 2006; Dorst 2011) and Participatory Design (e.g Sanders & Stapper 2008) particularly useful. The participatory element is critical. Research in WP highlights the role of partners outside the academy as sources of support for vulnerable learners. We treat working with partners to develop new materials and practices as a design problem, focussing on the learner, designing with and round their needs. In developing this approach we have come to think of the process of design, production and use as distinct but overlapping phases in the development of online material. The case studies are structured around these phases.

Read on for sections on:

Designing for Openness;

Exploring production practices;

Understanding Use Practices;

And Conclusion.

Designing for Openness

Introduction

This case study talks about what it means to design for openness in, for and through partnership. Some approaches to applying “Design Thinking” to education seem to utilise rather a thin interpretation of design; use cases, personas abound, language and approaches adopted (like the open licences themselves) from software development. While the tools are useful the sense of the learner as a customer consuming a product potentially exclude important aspects of educational practice. Here I detail the traps I avoided and the ones I fell into

First Steps

I had been porting design and User Experience (UX) tools into the development of OER for a number of years with mixed results. One of our early explorations of applying these techniques to learning was the development of a suite of learning materials for a national energy charity to support community groups to improve the energy performance of community builds. It presented some interesting design challenges, not least how to create an OER that went from online activities to offline action. We worked with front line staff who supported the organisation and, influenced by ideas around inquiry based learning, asked them to tell the story of a series of imagined communities. These stories were then woven through the materials to structure the learning. However, when we looked at use patterns we found users tended to be other support workers, and the resources were often being used as induction material for staff in energy charities and local authorities. We had used front line staff as a proxy for the learners, at the time I concluded that we often make openness in our own image (Macintyre 2013)

Design Probes

However, it was not the tendency for these tools and their outputs to be treated as a proxy for customers or learners needs that was the only issue. It was our own assumptions about what it meant (even in a participatory way) to design learning. I wanted to go back to the roots of design thinking and participatory design. In part that meant looking again at the literature, looking beyond recent applications in business and public policy (Brown & Martin 2015) it also required a greater willingness to critically engage with these tools in relation to practice and not simply apply the ideas in order to meet an end in creating learning materials. Following Sanders and Stapper (2008) call for participatory designers to explore different approaches I conducted a series of “design probes”. For example, building on a trusted relationship with social housing tenants we developed a suite of learning resources for those in fuel poverty designed and produced by those experiencing it themselves. I have also applied these approaches in schools (Macintyre 2014), and more recently with older people (Macintyre 2016a). The latter was in partnership with a UK wide conservation charity interested in how to engage older people in collecting biological data. We worked with a “design team” of older people to create appropriate approaches. Through these indirect approaches to designing learning we learnt a great deal. We learnt to ask questions of our assumptions and ourselves; we learnt that truly participatory approaches take time and effort; we learnt the limits of participation. I learnt how to handle the tools, when to talk and when to listen. Critically, I learnt the need to think about the process, the nature of the transformation for individuals and organisations, to think less about the “end product” and more about the process. Just as learners are in a state of becoming, changing through engagement with the learning process, so those involved in designing materials are also involved in a process of challenging our own and others assumptions, about accommodating the wants with needs, about the VALUE we as educators want to create and the VALUES of organisations.

Framing and Focus

Often as educators we start with what we know, and what we think people ought to know, and we have ways teaching. Advocates of online learning rightly note that classrooms are only part of the learning journey, and critique the assumptions of educators who ignore the affordances of online spaces. However, all educators make assumptions about HOW learning takes place. Online learning contains its own assumptions, for example constructivist pedagogies can make assumptions about levels of digital literacy that exclude some learners. Likewise those that argue we now live in a content rich world, where learning journeys might usefully be put together from “found content”, assume a degree of self-directed learning that tends to be a product of Western models of HE (Macintyre 2015; Macintyre 2016b). We have a series of intellectual shortcuts, successful approaches often applied tacitly that we use in situations (Corbett 2005). Based on the work of Dorst and Cross (Cross 2006; Dorst 2011; Dorst and Cross 2001) OEPS frames the design process as follows:

WHAT [is transformed] + HOW [it is transformed] = VALUE

Most of us have a strong senses of WHAT and HOW to solving problems, and learning design also frames approaches in certain ways, it is these heuristics that have interested us in OEPS. Work on tacit knowledge and its application has shown that successful problem solving is often based on framing the problem in relation to familiar approaches (Holcomb et.al 2009). However, research also shows they can also compound errors and reinforce practices that do not work (Kahneman 2012). My interest is not whether these heuristics are good or bad, but in creating a space where we can be open about them.

OPES does this by approaching the problem indirectly, starting with an exercise about the learner. Through this we tease out what we know, what we think we know, what we ought to know and what we will never know about the learner. This conversation creates uncertainty and deliberately obscures WHAT and HOW to focus on VALUE and VALUES. This is not learner as a customer with a fixed set of attributes, but learning as a state of becoming, with the focus on the transformations the learner and the provider need to undergo to achieve those VALUES. The tools themselves are not important, the OEPS workshops tend to draw heavily on approaches from Soft Systems (e.g. Armson 2011; Bell & Morse 2012) to understand and tease out visible and hidden assumptions. Often employing tried and tested techniques from other learning designers like storyboarding as well. Personally I have a particular fondness for spatialising and map making, asking people to walk in the footsteps of learners and make a map. I find this useful later when it comes to evaluation of use. The tools do not matter. For OEPS the important thing is to create a space for a conversation about what it is you want the learning materials to enable [VALUE], and how this fits within a broader organisational and social context [VALUES].

Exploring Production Practices

Introduction

It is easy to forget production; production can seem neutral, with the main questions about the technical affordances of the tools; or in relation to OER how well they support the 5R’s. As a social constructivist I think learning takes place when the learner “gets to work”, with the value of education constituted through the interactions, and for me these are socio-material/technical (Fenwick et.al 2011). While we often attend to the way knowing is constituted in learning, we often fail to interrogate what knowing in practice means for the production of learning materials. This case study, following on from the design case study, explores the questions our focus partnership, design and use have surfaced about production practices at Open University.

A Team Game

The Open University (OU) model of course development has always involved a process where the product is not simply a plan on paper delivered in the classroom. Nor is it the preserve of a solitary academic, or of groups of academics. It has always involved teams of media professionals, of technical experts drawn from diverse fields, from print, from radio, from TV. As Lane (2012) noted in his review of OER, the OU was uniquely placed to move into media rich, free open online learning as its existing production model was based on multi-disciplinary teams. This approach is not unique to the OU; many other Open and Distance Learning (ODL) providers have worked in this way, as do increasing numbers of campus providers as learning moves online.

Form and function, one follows the other. For many ODL providers the function has been to deliver high quality materials in a cost effective way at scale; for the OU the question of mass reach has been addressed through creating standardised content, customised through support structures. Content is produced in centralised teams, and the production line is probably the most appropriate representation. With different specialised teams performing separate functional roles with a degree of standardisation. New approaches layer over existing practices and a complex set of socio-technical relations are deposited over time. The layering of these strata become “the way we do things round here”. Of course it’s a lot messier than this, these are not neat production lines, but what is interesting is that when you are involved in a production system you rarely notice you are. Even the deviations and accommodations slowly developed over time to “get round a problem” are simply the pattern of daily activities, and there are often ambiguities around how some things are done, but it happens and it works.

In Plain Sight

The description above might seem familiar, as familiar as the local landmark you see tourists flock to but you have never visited. For me the assumptions about how we do things round here only became a place I wanted to visit when we looked to turn the resources and capabilities of the OU and realign them to face outwards and work in partnership. Indeed this took a number of years, as even though there was a commitment to partnership and designing in participatory ways, the structure of our design workshops was often based around ensuring the partner created content that fitted into our production processes. Actually partners did not mind, they were keen to learn about and have content produced in the “OU way”, and their interest and appreciation of the model reinforced our sense of it as an approach that produced the best quality materials.

However, as the design process became more participatory, and in particular as OEPS started to focus on VALUE and VALUES and making visible heuristics within the design process I started to question our own assumptions. Looking at HOW we do things round here. These become most apparent when things break down. The OU’s production line and degrees of specialism allow standardisation and economies of scale and scope. However, they rely on “academic authors” creating materials to a particular brief, and even when they do not, experienced Editors and producers shape the content into the appropriate form. They know what the form ought to be and act accordingly. In partnership, and in the open, where the form is not predetermined this becomes problematic. Specialisation and complex, and apparently resilient, production lines become uncomfortably long spans of control with distributed decision making. In our experience taking the resources and capabilities of the OU model and facing those outwards worked as long as partners wanted any kind of open as long as it was OU, the more participatory and open to partnership OEPS became the more difficult questions we asked of ourselves.

(re)Framing Production

At present OEPS is trying out new ways to approach the problem. The most obvious approach, and the one we have tested so far, is to move away from the OU production line structure and to stretch the metaphor, while still employing the production line tools and people but in a new configuration. Our first attempt suggests that a smaller team, with a Designer (managing relations with the partner and the process overall), authors (subject expert in the partner), and a hybrid Editor/Technical Producer (editorial style and also technical skills) can achieve time and cost savings. The approach is (to use the fashionable language influenced by Agile) to extend the earlier shop floor metaphor. Rather than specialists in a line it is more like the Japanese Kaizen approach, small teams of skilled generalists taking ownership. However, this has only run once. Whether and how it would work again is yet to be tested. I am mindful of the fragility of these small teams. For example, losing key members has been identified as an issue for small teams, and we have concerns regarding differing ways of working, personality clashes, annual leave, illness, and their potential to destabilise relations. There is a need to explore how stable the different work flows are. Long complex chains with specialist functions seems to offer stability, of great importance when you are creating 600 hours of accredited learning with a significant upfront cost. However, the established routines that provide the economies of scale and scope also make it difficult to change and adapt. The flexibility of smaller teams is being piloted for small units (5-25hours) of non-accredited learning. Can these approaches be scaled? These are interesting questions, and call to mind the work of complexity theorist Robert May (1973), whose modelling found simple systems are locally unstable, but globally stable (the classic example being the cycle of horseshoe hairs in the arctic tundra), while complex systems are locally stable but globally unstable (with tropical rainforest stability over time until suffering major perturbations a marker). I think to the question about scale lies in asking it again in a different way. How should they be scaled? Work on complexity and stability suggests creating small simple content development systems that allow for responsiveness, but also the need to buffer these to protect the learner experience.

Understanding Use Practices

Introduction

While these case studies started with design, OEPS thinking began with a concern for users and an exploration of use practices. Looking at how people were using OER led us to think about design, then production. This final case study looks at use practices, and shares some of what OEPS has learnt about use; first a general overview of OER users; then looking at a series of workshops with Union Learning Representatives (ULRs) who are exploring how OER can be used to support informal learning in the workplace; and finally a primary evaluation of an OER we have produced with Parkinson’s UK.

Learning about OER Users

There are significant constraints on our ability to track who uses free and open resources and how users work with them. We can collect analytics, but (as discussed below) there are limits to what can be gleaned from the data. It is not just the interpretive limits that make the OER community cautious about its data. Where we have user data it suggests that the socio-economic profile of users is skewed. As Laurillard noted on MOOCs, if they are the answer what was the problem? The data suggests the problem must be how we can ensure well educated professionals access free CPD (Laurillard 2014). It is a long way from the promise of OER to promote equity and social justice.

Where people have surfaced use information beyond the headline figures around educational attainment and income it makes interesting reading. For example, Knox (2014), who worked on the well-regarded online learning Masters programme at Edinburgh University, found that the materials released into the world bewildered even the experienced eLearning professionals who were the main audience. I will admit to a sense of being lost myself when taking the OU’s OLDS MOOC, based on found tools and constructivist pedagogy. It was interesting and to be admired in the same way one admires the artistry of a chef who deconstructs rhubarb and custard. If relatively well-educated education professionals were becoming lost, what did the playful and creative pedagogy do for uncertain learners distanced from education?

Learning from Others

Perryman and Coughlan (2014) have talked about opening up the HE led OER community to the broader sense of OER across a range of free platforms in their catchily titled “When Two Worlds Don’t Collide”; for us this is important as user communities’ voices are often neglected or accounted for through a thin veil of User Experience (UX). However, the title reminds us of others worlds that do not collide. Recently curating the digital strand (see here) at the OU’s national Widening Participation Conference (see here) I noted the WP community and the online learning community had few points of contact and dialogue. For example, in WP the P for participation is important, it implies something beyond access. However, the OER community has tended to focus on a necessary (but narrower) definition of open as access. To participate is something more, and these questions are explored in more detail below.

Learning from Users

In late summer, and then again in the Autumn/Winter 2015, OEPS ran a series of workshops with Union Learning Representatives (ULRs) (whose role is to support learning in the workplace); over a hundred ULRs took part. Often ULRs are supporting people with low levels and poor experiences of formal education, and many would consider themselves distanced from education, at least in some part of their lives. We asked them to think about what is meant to support online learning in the workplace, to think how they perform the role, what enables it to happen, what it enables for those that engage, and what might stop it from happening.

For most participants, and the people they support, the Internet was not seen as a space for learning. And even where they might be using it for learning (YouTube how to fix the washing machine) they did not think about in this way. Digging into this we found that many had conceptions of online learning shaped by the experience of workplace training, which they were compelled to do. Most found this a negative experience. When asked to explore free and open platforms people were interested, but a little overwhelmed by the choices and the way they were structured. As noted earlier, structural uncertainty is something even confident learners experience. Asked what would help, it became clear many had in mind a model of online learning that was about sitting in front of a computer at home, or in a training room at work. When participants started to think about other models that fitted with union values around collaboration and peer support they developed a different sense, seeing online learning as something that was supported through social structures; the ‘book group’ being the favoured metaphor. The links with the early miners and weavers libraries where people got together to support each other (Rose 2002) was compelling. You can read more here.

Learning in Partnership

These insights have informed OEPS understanding of design and production, we know structure is important, it needs to be clear; we know social support and ensuring learning is situated in peoples context is vital. Working with Parkinson’s UK to develop an entry level badged open course, aimed raising awareness of Parkinson’s amongst front line care staff, OEPS was able to apply these insights to the course design. As part of the evaluation I conducted a series of interviews and a focus group with a pilot group. Through the design Parkinson’s UK continually brought the learners back to practice, the course was about practice; learning was through practice and for practice. Participants felt the course did speak to their experience, and through videos of carers, family members and people with Parkinson’s, they learnt from practice. Participants found the reflective logs a familiar (well used in their contexts) and useful way to record and develop their understanding. They also talked about being ushered into new professional discourses, about being able to see more, being more confident to act as an advocate for those they care for, and in particular asking questions about the levels and organisation of services within their location.

Location was important, the pilot group was in a remote rural locale, service provision was thin, and people saw the course as developing systemic resilience where service often depends on individuals who might move away, become ill, or retire and not be replaced. Location also meant they were all familiar with ODL, mostly through work. The found the course easy to follow, the side menu was useful way to orientate, and what appears to be heavy repetition in a word processing document works online, as people dipped in and out of the material. Looking at the analytics most people were accessing the course through the Parkinson’s website, the “bounce rate” was lower than the OU average, and tended towards zero after the “Welcome Page”. When I started to look at the average time people spent on pages it was quite short. Half of the interviewees skimmed course pages and returned to read them in more detail later. However, participants tended to download the course as an interactive eBook. The offline reading “messes up” the data, and it also helped explain the difference between the familiar steep tailing away in page views, while the numbers engaging with quizzes (which have to done online) had a more gradual decline. Without talking to online learners about how they learn on the sofa, in the car between clients, juggling digital devices and notepads I would have struggled to make sense of the analytics and probably would not have discerned these patterns without talking to learner. In a world where apparently everything about a learner can be recorded it is useful to be reminded that only some of the traces of a learning journey are left on platforms. You can read more here.

Conclusion

Educational research has been reasonably good at surfacing assumptions about learners, at OEPS we are particularly indebted to work in WP which looked at the widening of access to HE in many jurisdictions and asked, why it has done little to broaden the socio-economic base of participants (e.g. Cannell et.al 2015; Cannell & Macintyre 2016). In doing so it surfaced visible and hidden barriers to participation, asking why we look to reshape the learner so they can participate rather reshaping the academy. In following these and applying them to OER participation we have surfaced further issues and questions around design, production and use.

These linked case studies started with design, through production ending with use. The narrative concludes that the sections are in the wrong order – use, the user, the learner comes first. The truth is far messier. We arrive with a sense of HOW it is to be done; with established production methods, with all their hidden assumptions, with ways of knowing about the world, knowing how to design materials, knowing what people need to know. We might also have a target audience, a particular “market segment” to be understood and targeted (not always in that order), or a neglected socio-economic group for whom we have received funding.

The messiness of educational practice described above inevitably collides with what educational research tells us, even our own. For example, while I might adhere to participatory methods I have also found truly participatory approaches are likely to have outcomes that do not sit well within our roles, with the funder or with the curriculum. Other researchers have noted in balancing these competing areas power imbalance, falsely raised expectations, and a sense of being exploited as potential risks for participants (Fenge at.al 2011; Pain et.al 2013). Equally, education materials are produced, not as bespoke creations based on individual’s needs, but for groups with diverse wants and needs, and in the case of OER intended and unintended audiences. Production at scale needs routines and assumptions on which to build efficiently and effectively. These are in place before we even meet the learner; the issue is how to work with them.

My sense is the design tools are not important, though it is important that they match the context. What is important is the underlying design ethos. Gradually through trial and error I have come to think of this in relation to VALUE and VALUES, the VALUE for the learner and for society and the organisation, the VALUES of the organisation and society. Thinking of the designerly role as one of an imperfect (often lost) explorer (with partners and participants) of Public Value (Moore 1995). It sounds rather grand and self-important, but at the same simple and somewhat banal. Banality is a good place to close, as the banal is often extra-ordinary hiding in plain sight.

Ronald Macintyre

March 2017

References:

Armson R. (2011) What? How? Why?: systems modelling for messy situations, in Armson R, Growing Wings on the Way: Systems Thinking for messy situations, Axminster: Triachy Press

Bell, S. and Morse, S. (2012) How people use Rich Pictures. In: Open University Colloquium. Pictures to Help People Think and Act. 07 March 2012, Open University, Milton Keynes.

Bathmaker, A.-M., Ingram, N., Waller, R. (2013). Higher education, social class and the mobilisation of capitals: recognising and playing the game. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 34(5-6), pp. 723–743.

Brown T. Martin R. (2015). Design for Action: How to use design thinking to make great things actually happen. Harvard Business Review, September 2015, pp56-64

Cannell, P., Macintyre, R. and Hewitt, L. (2015) ‘Widening access and OER: developing new practice’, Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 17(1), pp. 64-72.

Cannell P. & Macintyre R. (2016) Revisiting Barriers to Participation, Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, in press

Corbett, A. C. (2005). Experiential Learning Within the Process of Opportunity Identification and Exploitation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), pp. 473–491.

Cross, N. (2006). Designerly Ways of Knowing. Designerly Ways of Knowing. London: Springer-Verlag.

Dorst, K. (2011). The core of “design thinking” and its application. Design Studies, 32(6), pp. 521–532.

Dorst, K., & Cross, N. (2001). Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem–solution. Design Studies, 22(5), pp. 425–437.

Fenge, L.-A., Fannin, A., & Hicks, C. (2011). Co-production in scholarly activity: Valuing the social capital of lay people and volunteers. Journal of Social Work, 12(5), pp. 545–559.

Fenwick T., Edwards R., Sawchuk P. (2011) Emerging Approaches to Educational Research, London: Routledge

Fuller, A., and Paton, K. (2008) ‘Barriers’ to participation in higher education? Depends who you ask and how’, Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 10(2). pp. 6-17

Holcomb, T. R., Ireland, R. D., Holmes Jr., R. M., & Hitt, M. A. (2009). Architecture of Entrepreneurial Learning: Exploring the Link Among Heuristics, Knowledge, and Action. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(1), pp. 167–192.

Kahneman D. (2012) Thinking Fast Thinking Slow, London: Penguin Books

Kemmis, S. (2010). What is to be done? The place of action research. Educational Action Research, 18(4), pp. 417–427

Kemmis, S. (2006). Participatory action research and the public sphere. Educational Action Research, 14(4), pp. 459–476.

Knox J. (2014) Digital culture clash: “massive” education in the E-learning and Digital Cultures MOOC, Distance Education, 35(2), pp164-167

Lane, A. (2012) Collaborative Development of Open Educational Resources for Open and Distance Learning, HE Academy, http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/documents/oer/OER_CS_Andy_Lane_Collaborative_development_of_OER_for_distance%20learning.pdf [accessed 16th of August 2013]

Laurillard D. (2014) Which Problem could MOOCs solve, and how? MOOCs –Which Way Now?, University College London, 27th of June 2014

Levitas R. Pantazis C. Fahmy E. Gordon D. Lloyd E. Patsios D. (2007) The Multidimensional analysis of social exclusion Project Report by Bristol Institute of Public Affairs for the Department of Communities and Local Government, http://roar.uel.ac.uk/1781/1/multidimensional.pdf [accessed 27th of August 2015]

Macintyre, R., (2013). Open Educational Partnerships and Collective Learning. Journal of Interactive Media in Education. 2013(3), p.Art. 20

- (2014). Uncertainty, learning design, and interdisciplinarity: systems and design thinking in the school classroom. In: 4th International Conference Designs for Learning: Expanding the Field, 6 -9 May 2014, Stockholm. http://oro.open.ac.uk/40482/

- (2015). An Uneasy Relationship: Open Educational Practice and Neoliberalism. In: The 5th ICTs and Society-Conference: The Internet and Social Media at a Crossroads: Capitalism or Commonism? Perspectives for Critical Political Economy and Critical Theory, 3-7 June 2015, Vienna. http://oro.open.ac.uk/id/eprint/44846

- (2016a). Approaching Participatory Design in "Citizen Science". In: Design for Learning: 5th International Conference designing new learning ecologies, 18th -20th of May, Copenhagen. http://oro.open.ac.uk/46337/

-(2016b).Open Education and the Hidden Tariff. In: OEGlobal 2016: Convergence through Collaboration, 12th-14th of April, Krakow, Poland. http://oro.open.ac.uk/id/eprint/46044

May R. (1973) Qualitative Stability in Model Ecosystems, Nature, 54(3), pp638-641

Moore, M. (1995) Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government, Harvard University Press Cambridge, MA

Pain, R. et al., 2013. Productive tensions—engaging geography students in participatory action research with communities. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 37(1), pp.28–43.

Perryman, L. and Coughlan, T. (2014). When two worlds don’t collide: can social curation address the marginalisation of open educational practices and resources from outside academia? Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2014(2), article no. 3

Rose J. (2002) The Intellectual Life of the British Working Class, London: Yale University Press

Sanders, E. B.-N., & Stappers, P. J. (2014). Probes, toolkits and prototypes: three approaches to making in codesigning. CoDesign, 10(1), pp. 5–14.

Sanders, E. B.-N., & Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4(1), pp. 5–18.