Developing business models for open, online education

Introduction

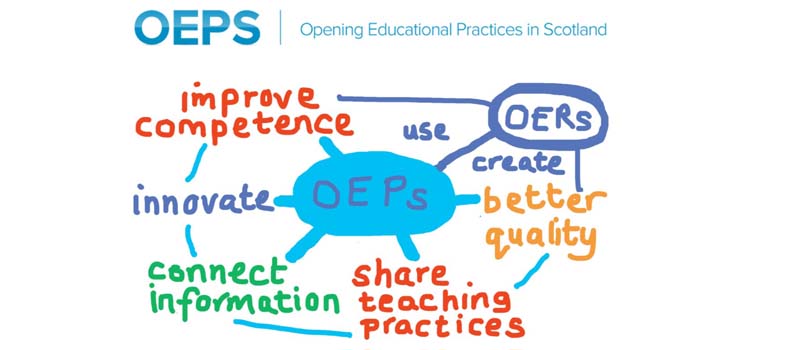

OU This report is concerned with ‘open’ in the context of the creation and use of openly licensed educational materials. It explores the challenges and opportunities that this new and evolving field present for universities and colleges in Scotland.

This report is concerned with ‘open’ in the context of the creation and use of openly licensed educational materials. It explores the challenges and opportunities that this new and evolving field present for universities and colleges in Scotland.

While its roots lie in older notions of ‘open’ and links to the open source software movement, the beginning of the ‘open education movement’ is usually dated from the launch of the Open Courseware programme in 2002. In this initiative the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) made large amounts of the university’s educational material available online; free to use, share and reversion. The initiative had international impact. Five years later the Cape Town declaration highlighted the promise of open education and noted that fulfilling the promise required attention to pedagogy and practice. In the same year ‘Giving Knowledge for Free’ published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development took an in depth look at the emergence of what had become known as Open Educational Resources (OER) and discussed the development of sustainable cost/benefit models for OER initiatives.

Open educational resources (OER) are educational materials that are available with an open or Creative Commons license that enables unfettered use free of charge to the user and, depending on the form of the license, also allows for the material to be modified and mixed with other similarly licensed material to make new resources.

For more information go to www.creativecommons.org

In the decade following the Cape Town declaration the impact of openly licensed educational material has been significant but has not had the disruptive influence on education that some people expected. Recent discussion and debate has been dominated by attention to Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). MOOCs hit the headlines in the autumn of 2011 when Stanford University launched an open online course ‘Introduction to AI’ which attracted 160,000 enrolments. MOOCs are open in the sense of being free to use with no requirement for entry qualifications; they are not necessarily OER since only some are openly licensed. The public profile these new courses achieved and the need for educational institutions to tackle pedagogical and technical issues as they started to create courses for the new MOOC platforms raised the profile of open education in mainstream higher education. On the other hand there has been a tendency for the MOOC model to become synonymous with online courses, a development that may detract from considering alternative models. In this report we focus on business models for openly licensed courses although much of the discussion can be extended to MOOCs.

A decade ago the OECD report on open educational resources argued that the case for OER was founded on:

Altruism, leveraging taxpayers’ money; efficiency in cutting content development costs; providing a showcase to attract new students; offering potential students a taster of paid-for content; and to stimulate internal development and innovation (OECD, 2007, pp. 64-5).

Five years later Stacey (2012) expanded this list to include ten benefits of OER initiatives to educational institutions:

Increasing access to education; providing students with an opportunity to assess and plan their education choices; showcasing an institution’s intellectual outputs, promoting its profile and attracting students; converting students into fee paying enrolments; accelerating learning; adding value to knowledge production; reducing faculty preparation time; generating cost savings; enhancing quality; and generating innovation through collaboration.

More recently four specific areas of opportunity for universities have been identified: linking students to employers, creating revenue through the sale of certificates, blending with or replacing face to face courses and attracting new students Burd et al (2015).

The context for universities is also affected by growing competition from commercial companies in the provision of short courses for professional development. In addition MOOC platforms are linking up with business to support skills training. For example, Coursera have partnered with AXA insurance. However, competition from outside the education sector is not restricted to professional development. In July 2017 Amazon launched its Inspire platform that aims to provide OER for teachers in the US.

In the remainder of this report we build on these insights to categorise areas of potential benefit for Scottish colleges and universities, drawing on experience garnered by the OEPS team working with educators and practitioners in Scotland from summer 2014 until summer 2017.

Developing new models

Open education is a new and emerging field. As a result there are no well-established business models. Furthermore, institutional benefit depends on the use that is made of ‘open’ and is contingent on institutional mission, policy, practice and context. With these provisos we provide a discussion of six overlapping areas that provide opportunities for the sector.

1. Institutional profile

Enhancing reputation is one of the primary reasons why some universities are involved in MOOC production. Beyond the MOOC agenda, however, there is an emerging trend, for the development of websites that showcase openly licensed materials; highlighting the range of the universities interests and specialist areas of expertise. Showcasing research outputs in open formats can add to their impact and contribute to the REF. In addition, by enabling sharing and reuse, these sites have the potential to create local, national and global communities around the use of open resources. There are currently three such sites associated with Scottish universities: Open.Ed at The University of Edinburgh; edshare@GCU at Glasgow Caledonian University and OpenLearn at the Open University.

Reputation and student recruitment are linked. The ‘brand’ profile of the institution can be expected to affect undergraduate and postgraduate applications. However, it is also possible to use open resources more proactively. For example, the Open University has a strategic approach to encouraging transitions from informal to formal learning. OpenLearn gives access to large numbers of short openly licensed courses, together with a wide range of other openly licensed materials including articles, videos and quizzes. Some of the courses are specifically designed to support transitions from informal to formal study. The site has more than six million new visitors each year and although the percentage of these going on to further study is small the revenue generated makes a significant contribution to the costs of maintaining and developing the site.

2. Public good

Initiatives taken to promote public good may well overlap with considerations of institutional profile. However, they can also form part of a broader philosophical approach to openness that includes open data, open research and the use of open source software. Activities that contribute to the public good may be part of the university mission but increasingly aspects of openness are encouraged or mandated by legislation. Considerations of public good are particularly relevant in Scotland in a context where higher and further education is publicly funded and each university and college negotiates an outcome agreement with the Scottish Funding Council. Public good initiatives can form part of a strategy to encourage charitable donations.

3. Knowledge Exchange

Traditional knowledge exchange models operate through the sharing of research, advice, consultancy and public lectures or workshops. However, in a digital world, web based approaches to sharing knowledge can potentially have greater impact and reach. In particular it allows for dissemination and dialogue, locally, nationally and internationally.

The OEPS project found significant interest in using open education to support knowledge exchange from universities and from organisations in the informal learning sector. Examples include:

The co-production of an openly licensed course on seaweed parasites, My Seaweed Looks Weird, with the Scottish Association for Marine Science (University of the Highlands and Islands), which was linked to a Nuffield Trust grant.

The co-production of a short openly licensed course, Global Trends in Death and Dying, with a Wellcome Foundation funded research team based at the University of Glasgow Crichton Campus.

Two specialist courses on advanced aspects of Parkinson’s, co-created with Parkinson’s UK and expert practitioners and three courses co-created with Dyslexia Scotland.

In the case of the Parkinson’s courses there was a dual objective; firstly to support medical and healthcare practitioners; secondly to provide high quality, cutting edge resources that could be used, blended or remixed by universities.

From an income generation perspective, knowledge exchange metrics are not currently designed to support digital knowledge dissemination. However, there is a strong case for this to be reviewed.

4. Curriculum Development

There are emerging examples of open course material being incorporated into the mainstream curriculum. This can take a variety of forms:

![]() Using openly

licensed learning materials as part of a module.

Using openly

licensed learning materials as part of a module.

![]() Embedding the

study of a short open course in a larger accredited module.

Embedding the

study of a short open course in a larger accredited module.

![]() Providing (a

paid for) assessment module that enable students to earn academic credit after

studying a number of short open courses.

The University of Leeds and others are using this approach for MOOC

study on the FutureLearn platform and by the Open University on OpenLearn.

Providing (a

paid for) assessment module that enable students to earn academic credit after

studying a number of short open courses.

The University of Leeds and others are using this approach for MOOC

study on the FutureLearn platform and by the Open University on OpenLearn.

![]() Using an empty box module that links prior

informal badged learning with accredited study by recognising and valuing the

non-accredited study while using it as a launch pad for further formal

study. The Open University is

piloting this approach with a 30-credit, SCQF level 7 module, ‘Making Your

Learning Count’.

Using an empty box module that links prior

informal badged learning with accredited study by recognising and valuing the

non-accredited study while using it as a launch pad for further formal

study. The Open University is

piloting this approach with a 30-credit, SCQF level 7 module, ‘Making Your

Learning Count’.

![]() Collaborative development of degree

programmes comprising free openly licensed resources from a single institution

or from multiple institutions, with the student able to opt to pay for

assessment. The University

for the People and the Saylor

Academy in the US offer

this model, as does the OERu, which is an international consortium that includes the University of

the Highlands and Islands and the Open University.

Collaborative development of degree

programmes comprising free openly licensed resources from a single institution

or from multiple institutions, with the student able to opt to pay for

assessment. The University

for the People and the Saylor

Academy in the US offer

this model, as does the OERu, which is an international consortium that includes the University of

the Highlands and Islands and the Open University.

However, open licensing also poses more fundamental challenges for academic practice and traditional models of curriculum development. Increasingly good quality content is readily available online. On the other hand curriculum development tends to take place within institutional boundaries and is ‘fenced off’ within Virtual Learning Environments. From a student perspective however, traditional boundaries make little sense. They can and do access open content from the internet and indeed may share material from the VLE in the open.

There are also challenges to the ways in which new modules are created. In the US the large scale support for the use of Open Text Books is resulting in the production of high quality openly licensed texts that pool the knowledge of multiple authors and continually evolving as the material is edited, reversioned and remixed. Critically they can also be reversioned and contextualised for particular contexts. This approach could be used in the production of other educational materials and indeed for entire online or blended modules (see the OERu example above). There is the potential to create virtuous cycles of development, however, when content is ubiquitous and collaboratively created it challenges institutions to articulate the value that their approach to teaching and learning brings.

5. Educational Transitions and widening participation

The OEPS project had an overarching focus on issues of equity and social justice in the use of openly licensed educational resources. The open education movement has highlighted the potential for OER to open up opportunity to ‘non-traditional’ students. However, the evidence suggests that simply being free and open is not enough to enable the promise of OER to be fulfilled. OEPS worked with a wide range of partners to explore barriers to participation. Important factors include:

· Perceptions of online learning as individualised and isolating

· An assumption that online means tick box and unengaging

· Lack of recognition by learners and/or providers of the value of the experience that learners bring to their studies

· Lack of support for developing digital literacy

· Absence of clear pathways through the huge range of available materials

· Insufficient attention by providers to the curation of resources

In order to widen participation it is necessary to bring together approaches from widening participation with the affordances of openly licensed materials. Student centred pedagogy that recognises context and is aware of the situational, affective and institutional barriers to engagement is critical. Provided these issues are addressed then OER can make an important contribution to support learning journeys.

It has been recognised for a long time that for many non-traditional learners routes into formal education begin with part-time, informal learning. However, the informal environment has changed radically and now includes large amounts of online material. By itself this can constitute another barrier to participation. There are opportunities widening participation practitioners to work together with learning technologists and organisations that support non-traditional learners to transform this situation. Well-structured and supported materials can be designed to fill gaps in the complex pathways that learners experience before they enrol for a formal qualification. Open licensing allows tried and tested material to be contextualised for specific contexts and brought together to form supported pathways appropriate to particular groups of learners. This approach is being piloted by Unite the Union on its learning website with the support of the OEPS project. Another example is the Open University in Scotland’s ‘Open Pathways to Higher Education’ initiative which provides a small number of flexible pathways through informal to formal learning.

The OEPS project found a high level of interest and demand in the informal sector.

The University of Dundee uses Open Badges to recognise co-and extra-curricular activities on its undergraduate Law Degree to support transitions from education to employment. This initiative is generating interest in the Scottish university sector and could be extended to use badged open courses.

6. Professional development and communities of practice

The OEPS project uncovered a considerable interest in the use of short, openly licensed online courses to support professional development. Much of this was in areas of professional practice where there is a need for staff to keep up with new developments in knowledge, practice and regulations. Currently the formal sector has a focus on qualifications and credentials. These are important and essential but requiring significant inputs of time and commitment they fail to meet the needs of many organisations and individuals. Doug Belshaw makes the distinction between ‘old school’ and ‘new school’ credentials. ‘Old school’ courses are lengthy and formally accredited. A learning landscape filled with such courses leaves multiple specialist gaps, which impede flexibility and progression by learners. ‘New school’ is more granular, comprising shorter informal courses, which fill the gaps, allowing flexibility and progression. The experience of the OEPS project suggests that there is demand for a more granular approach to professional development in a number of areas, particularly those in which there is a focus on professional practice.

As part of its commitment to produce exemplar online courses OEPS worked with Parkinson’s UK, Dyslexia Scotland and the Equality Challenge Unit to produce short professional development courses. Working in partnership had benefits for both partners and encouraged knowledge exchange. This model of production has potential for much wider use. A strategy of developing short, openly licensed professional development courses is then not an alternative to a formal curriculum. The two can be intimately related; supporting students who have completed one stage of the qualification route and who are now in work and potentially encouraging them back at a later stage. If informal course development is carried out in partnership it can also support two-way knowledge exchange, with the institution sharing cutting edge theoretical insights at the same time as practitioners share practice based knowledge.

Production models and production costs

The MOOC model has dominated much of the discussion around the costs of producing open online courses. While many institutions become involved in MOOCs to enhance reputation there is also a strong interest in sustainable business models in which income generation exceeds production costs. We noted above that increased student recruitment is one such mechanism. Most MOOC platforms are now developing strategies that maintain open access to content (although this is usually time limited) with charges for certification and other additional premium services. In the US in particular, some MOOC providers are also using diversifying into private online courses with paid for content.

The MOOC model is relatively high cost and platforms like FutureLearn, which carry courses from multiple providers, insist on high production values. While costs depend on a range of factors the cost of producing a MOOC (usually in the range 12 to 30 study hours) is typically in the range £30,000 to £100,000.

The biggest contributions to the cost of producing online courses are: the cost of writing, editing and uploading new content, the costs of filming and editing high quality video and audio, and the costs of coding forms of animation or interactivity that are not automatically supported by the platform. Other costs are typically smaller but do vary according to institutional capacity and expertise. In producing exemplar openly licensed courses the OEPS project worked primarily in partnership with other organisations. While partnership produces its own challenges, sharing expertise and resources and making maximum use of existing openly licensed resources tended to reduce costs. The OEPS model was essentially a bottom up model and engaged much more specific audiences than is normally the case for MOOCs. Marginal costs of production varied primarily according to media mix but tended to be in the range £1500 - £2500 per hour of content.

Currently a limiting factor for innovative and large-scale development of short open courses is the limited range of open platforms. The understandable interest in hosting on institutional sites does increase costs since each institution has to carry costs of development and maintenance. With the demise of the JISC supported OER repository site JORUM there are very few open sites not linked to commercial providers that provide tools and support for course development. This was the reason why the OEPS project opted to use OpenLearn Create to host its exemplar courses and its legacy materials. It’s likely that the functionality of OpenLearn Create will be further enhanced in 2018 to include a user friendly authoring tool which will make the process of course creation much less dependent on the involvement of technical expertise.

Conclusion

Open education remains an immature and evolving field. This report suggests that while modes of engagement for colleges and universities are contextual and mission dependent, there is a strong case for developing institutional policy and practice. Currently policy in Scotland is skewed by an over emphasis on MOOCs, which form just one part of a wider landscape.

The categorisation of opportunities outlined in this report is provisional and there are significant overlaps and synergies between them. It’s already the case for example that institutions that have opted to offer MOOCs have tended to enhance their ability to develop a broader online curriculum. It’s likely that genuinely sustainable business models will depend on combining policy and practice across a range of different areas of application.

Institutions could choose to approach new policy and practice from a student perspective; considering how best to meet expectations and provide support in a world where content is ubiquitous. Such an approach would also require consideration of the role of academics and new approaches to curriculum design.

Policy and practice could also be addressed from the perspective of organisations outside the academy. The OEPS project found significant interest in open education, and considerable demand for closer collaboration with colleges and universities, from these organisations.

Further reading

Burd, E., Smith, S. and Reisman, S. (2015) Exploring Business models for MOOCs in Higher Education. Innovations in Higher Education, 40, pp 37-49.

Law, P. and Perryman, L. (2017) How OpenLearn supports a business model for OER. Distance Education, 38(1) pp. 5–22.

OECD (2007) OECD (2007) Giving Knowledge for Free: the emergence of open educational resources. OECD/CERI. Available from http://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/38654317.pdf

Stacey, P. (2012) The economics of open [blog post]. Available from http://edtechfrontier.com/. [Accessed 15 The Open University’s Open Educational Media Operating Policy can be accessed at http://www.open.ac.uk/about/open-educational-resources/what-we-do/open-educational-media-operating-policy

The OEPS collection of courses, papers, reports, briefings and resources can be accessed at www.open.edu/openlearncreate/oeps

You can download this report as a document or a