Are ‘open’ and online reconfiguring learner journeys?

This report looks at the ways in which OER and OEP can support educational transitions it was presented at the 2017 Enhancement Themes Conference on June 8th

Abstract

This paper draws on evidence and insights from Opening Educational Practices in Scotland (OEPS), a three years project supported by the Scottish Funding Council and led by the Open University in Scotland, which concluded at the end of July 2017. The project worked with partners across the formal and informal education sectors to develop good practice in the creation and use of openly licensed free online courses. The project remit was to look at ‘open education’ and the affordances of open licensing through the lens of widening participation. While the project worked on a broad canvas, a significant part of its activity was concerned with the value of open approaches and the use of openly licensed resources in ‘in between spaces’. From a learner perspective these spaces are often about educational transitions; from informal or self-directed to formal learning; between sectors and between education and employment. All of these transitions are negotiated in environments within which digital technology is becoming ubiquitous. As a result barriers to transition are reconfigured. We share evidence and insights from partners and students and look at some emerging models of good pedagogic practice designed to support students for whom online and open is becoming an important part of the transition from informal to formal learning.

Introduction – about OEPS

In 2014 the Scottish Funding Council commissioned a three-year project, Opening Education Practices in Scotland (OEPS), to consider how free, openly licensed courses might contribute to widening participation (Cannell et al, 2016). Policy makers and researchers have noted the potential of such courses to break down traditional barriers to participation in education (D’Antoni, 2009). In practice, however, these new developments have had a very limited impact on lifelong learning (Falconer et al, 2014). Indeed there were only a small number of examples of using openly licensed material in explicitly widening participation contexts for the project to draw on (Lane and Van Dorp, 2011; Cannell, 2013) and few links in Scotland or internationally between the educational technology and widening participation practitioner communities. In view of this, the project operated from the outset as a set of collaborative initiatives, working with partners across Scotland. Over the three years this involved sixty-five organisations including universities, colleges, third sector organisations, trade unions and employers.

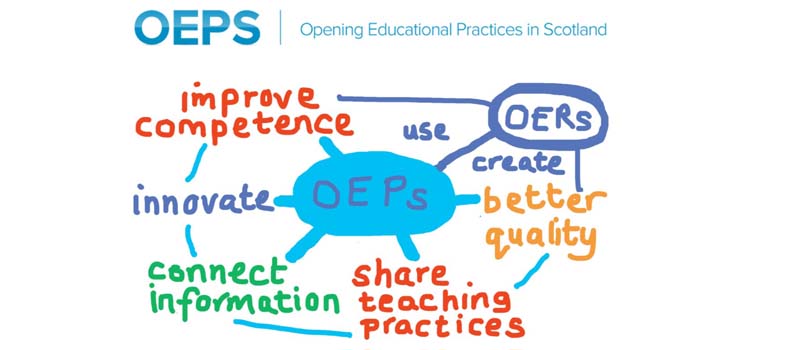

OER and OEP

In 2002 the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) made large amounts of the university’s educational resources available online; free to use, share and reversion. This Open Courseware initiative marked the beginning of what is often referred to as the ‘open education movement’. At the heart of the movement is Open Educational Resources (OER). These are educational materials that are available with a Creative Commons license that enables unfettered use, free of charge to the user and, depending on the form of the license, also allows for the material to be modified and mixed with other similarly licensed material to make new resources. Just five years after MIT’s initiative the Cape Town declaration (2007) highlighted the promise of open education, emphasising that making free, open resources available to all required attention to pedagogy and practice. The Cape Town declaration noted that:

‘… open education is not limited to just open educational resources. It also draws upon open technologies that facilitate collaborative, flexible learning and the open sharing of teaching practices that empower educators to benefit from the best ideas of their colleagues. It may also grow to include new approaches to assessment, accreditation and collaborative learning’.

This sense of open as about educational practice, as something more than a technical issue was central to the OEPS project.

Widening participation in a digital world

The Open Courseware initiative heralded a rapid increase in the availability of free openly licensed educational resources online. Initially OER were mainly learning objects; lecture notes, videos, images etc. More recently in the United States there has been a massive expansion in the availability of free openly licensed textbooks. In the UK the initial focus was on learning objects, small shareable bits of learning materials often shared between educators, however this has now shifted onto courses aimed specifically at learners. These changed coincided with the rapid extension in access to, and the use of, digital technology. An OFCOM report[1] published in 2015 highlights the trend towards greater ownership of mobile devices; 66% of UK adults owned a Smartphone in 2015, up from 39% just three years before.

In the light of its widening participation remit the OEPS project paid particular attention to journeys from informal to formal learning. These learner journeys are often complex and non-linear but the support of trusted gatekeepers from the informal learning sector (Cannell et al, 2015) is often critical to successful progress. Until recently these organisations tended to avoid the use of digital technology to support access to learning since access to or ownership of a computer was out of reach for their learners. However, the rapid growth in use of mobile digital devices has had a significant impact on policy and practice. In most cases supporting learners to obtain digital skills is now seen as an essential prerequisite for engaging with learning.

The informal sector in Scotland has traditionally relied on part-time short courses in the college sector or local authority run Community Learning Development. However, these sources of support are much reduced (Galloway, 2016); a phenomenon that is apparent across the UK (Rose Adams and Butcher, 2015). Increasingly organisations are looking to online courses for support.

Open online courses – a new learning landscape?

From the learner perspective there is now a bewildering number of free courses available online. Some are in the form of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs); courses that are open to all and free to use. However, MOOCs are only presented for limited periods, at fixed dates, and in most instances the materials are copyright. They can be a valuable resource for learners but their limited availability can be problematic for organisations supporting learners. Increasingly MOOC platforms also charge for credentials. However, the availability of free, openly licensed courses that are always available is also growing fast. The Open Universities OpenLearn site, for example, has many thousands of hours of learning material and also dedicated courses aimed at supporting educational transitions.

Typically open online courses are relatively short. In most case the number of study hours is in the range five to twenty-five, although there are outliers at both ends of the range. From the perspective of learning providers the granularity of short open courses offers potential flexibility and the ability to fill ‘in between spaces’ tailoring provision to learner needs and context. However, granularity can also add to complexity and create new kinds of barriers. In our work we have found the legacy of learning objects as discrete items for fellow educators often lives on in the development of courses, which often assume levels of prior knowledge. Coupled with the sheer volume of resources it can be hard for uncertain learners, and indeed organisations, to locate appropriate resources. With this “tyranny of abundance” creating barriers.

Where learning is recognised credentials tend to take the form of certificates or digital badges. In some instance these may simply recognise participation but increasingly micro-credentials are awarded against specified assessment criteria linked to explicit learning outcomes.

All these developments suggest that there has been a signification shift in the informal learning terrain that non-traditional learners have to traverse. But learners also undertake learning journeys with different prior experience than in the past. Very few learners will have had no contact with the digital world. Indeed most have experience of using Google and YouTube as resource for self-directed learning. Yet evidence from OEPS action research (Cannell and Macintyre, 2017) suggests that this experience is seldom understood or valued as learning. So learner journeys take place in an environment where digital resources are ubiquitous and where non-traditional learners have to negotiate important transitions from self-directed to more structured informal learning in the form of short courses and then further transitions from informal to formal learning.

Pedagogy for supporting participation and transitions

While it’s now a decade since the Cape Town Declaration drew attention to the fact that ‘open’ education is about more than the technology, there has been a persistent tendency to assume that issues of participation are amenable to technological solutions. The OEPS project worked with third sector and trade union partners to uncover the reasons why the demographics of participation have been so skewed towards individuals with prior experience of HE. The project findings are discussed in Cannell and Macintyre (2017) in a number of reports and briefings in the OEPS legacy[2] collection. Critical factors include:

· Perceptions of online learning as individualised and isolating

· An assumption that online means tick box and unengaging

· Lack of recognition by learners and/or providers of the value of the experience that learners bring to their studies

· Lack of support for developing digital literacy

· Absence of clear pathways through the huge range of available materials

· Insufficient attention by providers to the curation of resources

Students starting on a journey through informal to formal learning may have a whole range of views about learning conditioned by prior experience that often includes online and may include ‘open’. It is now possible to assume that almost all prospective students in higher education have some experience of the digital world and access to some kind of digital device. This familiarity, however, doesn’t necessarily mean that students arrive in higher education with appropriate skills or confidence for learning. It is important to differentiate between different forms of digital literacy, for example between the ability to share something online and to use the internet as a source of learning or indeed to use trusted sources. This is true for students across the age range; the digital native characterisation is often not helpful when thinking about skills for learning in HE.

The widening participation literature includes well-grounded discussion of why widening participation is more than access, and on the multiple barriers to participation and transition (see for example Fuller and Paton, 2008). In the context of digital participation and online courses, the OEPS project found that the classification of barriers into situational, dispositional and institutional remains valid. Each, however, needs thorough re-examination in the digital world. Perhaps most important are the preconceptions that learners and providers of learning can bring. For example, there is a tendency to see online learning as individualised. In reality learning always takes place in a social context and early feedback from the project suggests that designing courses and social support for students in ways that maximises opportunities for peer support and interaction has a positive impact on retention and success. The OEPS project found it helpful to extend notions of Open Educational Practice to include social practices that mediate between providers, partners and learners.

Conclusion

The use of openly licensed courses is in its infancy and the field continues to evolve and mature. There are pockets of innovative practice around the Scottish sector. Many of these are documented in the OEPS legacy collection. However, the new landscape of educational provision together with the ubiquity of digital experience among potential learners presents new challenges for higher education and particular for the support of successful transitions into formal study. The findings of the OEPS project suggest that there is a need for greater recognition of the impact of the digital world on learners and greater attention for recognising, supporting and developing digital participation and digital literacy skills. Perhaps most important, however, is the need to rethink the relationship between informal and formal in a world where good quality ‘content ‘ is widely available. The OEPS work on barriers to engagement suggests that unless there is a reorientation on the pedagogy of transition, involving new approaches to design, curation and support, the promise of OER may not be realised.

References

Cannell, P. (2013) ‘Exploring open educational practice in an open university’. In: UNISA Cambridge International Conference in Open, Distance and eLearning, 29 September - 2 October 2013, Stellenbosch, South Africa. http://oro.open.ac.uk/42127/ (accessed 28 April 2017)

Cannell, P., Macintyre, R. and Hewitt, L. (2015) ‘Widening access and OER: developing new practice’, Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 17 (1)1, 64-72.

Cannell, P., Page, A. and Macintyre, R., (2016) ‘Opening Educational Practices in Scotland (OEPS)’, Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2016 (1), 12 - . DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jime.412 (accessed 28 April 2017)

Cannell, P. and Macintyre, R. (2017) ‘Free open online resources in workplace and community settings – a case study in overcoming barriers’, Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 19(1), 111-122.

D’Antoni, S. (2009) ‘Editorial: Open Educational Resources: reviewing initiatives

and issues’, Open Learning, 24 (1), 3–10.

Cape Town Declaration (2007) Cape Town Open Education Declaration. (accessed 12 July 2017)

Fuller, A., and Paton, K. (2008) ‘Barriers’ to participation in higher education? Depends who you ask and how’, Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 10, 2: 6-17.

Galloway, S. (2016) ‘Adult literacies in Scotland: is social practice being buried alive?’ In: James, N. (ed.) Adult Education in Austere Times: SCUTREA Conference Proceedings, Leicester, 95 – 101.

Lane, A. and Van Dorp, K. J. (2011). Open educational resources and widening participation in higher education: innovations and lessons from open universities. In: EDULEARN11, the 3rd annual International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, 04-05 July 2011, Barcelona. http://oro.open.ac.uk/29201/ (accessed 10 July 2017)

Rose-Adams, J. and Butcher, J. (2015) Distance Education In European Higher Education - The Potential: UK Case Study, Oslo, International Council for Open and Distance Education.

This report was written for and presented at the 2017 Enhancement Themes Conference and can also be found on the Enhancement Themes website