Breaking down barriers to widening participation - using open online courses in lifelong learning

Breaking down barriers to widening participation

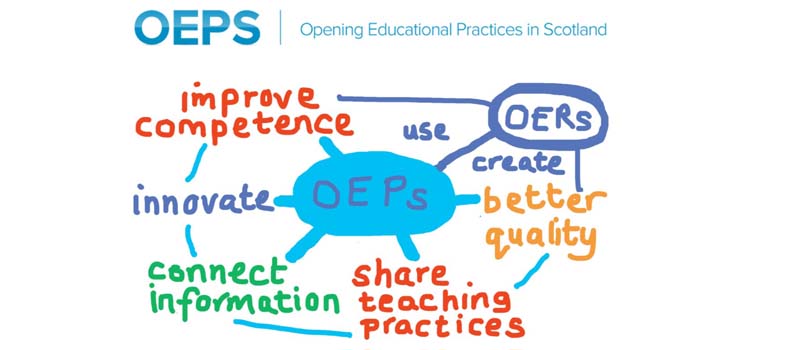

About OEPS

Opening Educational Practices in Scotland (OEPS) was a cross-sector open education project, funded by the Scottish Funding Council and led by the Open University in Scotland. The OEPS remit was to identify and develop good practice in the use of Open Educational Resources (OER) in Scotland, with a particular emphasis on widening participation and transitions into, through and between education and employment.

About this report

This report is written to support practitioners and policy makers in the field of widening participation and lifelong learning. It summarises good practice distilled from the practice-based experience of the many partners that OEPS has worked with during the course of the project and also from our reading of the widening participation and open education literature. The report is in two parts; in the first we discuss barriers to participation; in the second we provide suggestions for how barriers can be overcome. We would like to acknowledge a debt to the large number of people who have shared their knowledge and experience with the project team.

Section 1: Understanding barriers to participation

Introduction

We live at a time of rapid change in access to, and use of, digital technology. An OFCOM report published in 2015 highlights the trend towards greater ownership of mobile devices; 66% of UK adults owned a Smartphone in 2015, up from 39% just three years before. Digital technology permeates multiple dimensions of our lives.

Using digital technology for learning is not just about devices and connectivity. In a very short space of time Google, YouTube and Wikipedia have become part of everyday life. As part of the OEPS project we ran a series of workshops with adult learners in 2015 and 2016. At each workshop we began by asking participants about their use of digital technology. Every one of the workshop participants used Google for informal learning activities.

At the same time there has also been a huge increase in the availability of free online courses. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have had a high media profile. However, there are also a large number of free courses available on other websites – many issued under open licenses that allow copying, reuse, remixing and reversioning. These openly licensed courses are known as Open Educational Resources (OER).

This report explores the opportunities and challenges that ubiquitous digital technology and free open, online courses present for equity and access in adult learning.

Massive Open Online Courses

Good quality free online courses are also available in the form of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs)[1]. In most cases MOOCs are not openly licensed. While the mass scale at which they operate extends access, overall the opportunities to study via this medium are mainly taken up by individuals with graduate level qualifications. Nevertheless, MOOCs form an important part of the new online learning landscape and we include them in our discussion.

Open Educational Resources

Open educational resources (OER) are educational materials that are available with an open or Creative Commons license that enables unfettered use free of charge to the user and, depending on the form of the license, also allows for the material to be modified and mixed with other similarly licensed material to make new resources.

The promise of open online courses

Educationalists, researchers and policy makers have suggested that open online courses offer opportunities to enhance and widen participation in lifelong learning. However, the evidence is that this has not yet happened on a significant scale. In the rest of this report we consider reasons why this is the case and propose ideas for policy and practice, which may enable much wider participation.

Barriers to participation

There is an extensive literature (see further reading) on the barriers that adult learners encounter to participation in formal education. Barriers can be categorised as situational, institutional and dispositional. Situational barriers apply to the learner and include socio-economic disadvantage, prior educational experience, geographical location and disability. Institutional barriers arise when support systems, procedures and curriculum are poorly aligned with learners’ needs. Dispositional barriers refer to the subjective impact of prior experiences, which can mean that individuals lack confidence, may be reluctant to engage with learning opportunities, or drop out once they have started. Recent research has highlighted that it important to understand barriers to participation as both gendered and racialised.

For many non-traditional learners the route into sustained and successful engagement with formal education is often through part-time, informal study and negotiated with the support and encouragement of trusted intermediaries. Intermediaries may be part of college or university outreach teams, or work for third sector organisations, unions and other similar organisations.

Cost

Course fees and the costs of study constitute a barrier to participation for individual learners. The cost of producing good quality material or providing tutorial support may also be a challenge for organisations that support transitions into formal study. Thus the availability of a wide and varied range of free, good quality online learning material in the form of OER is an attractive option. However, experience suggests that while being able to offer opportunities at low or no cost is important it is insufficient.

Studying in a digital world

More and more potential students have access to digital devices. The OFCOM report highlighted in the introduction noted a rapid increase in ownership of online devices; the same report found that in 2015, 90% of 16 – 24 years olds owned a smart phone. Nevertheless, digital exclusion remains an issue. A 2013 report on digital exclusion in Glasgow noted the complexity of the factors that are connected to lack of Internet use:

‘A successful approach to tackling digital exclusion must recognise the different attitudes which citizens have towards the internet and take the needs and motivations of each individual as the starting point for providing help and support’.

However, as access to technology grows some authors have pointed to the emergence of a new digital divide. In some accounts this second divide is related to access to broadband; this certainly remains an issue for many learners in rural Scotland. However, the OECD also draws attention to the importance of skills. And even when students and prospective students have skills appropriate to a range of ‘everyday’ digital tasks it doesn’t necessarily follow that they have appropriate digital literacy skills to make good use of online learning materials. The absence of these skills is a barrier to participation. Supporting students to develop appropriate skills is a critical challenge for institutions.

It is also important to recognise that institutional and dispositional factors that present barriers for novice learners intersect and interact with specific features of the online environment. Free open courses are typically located in online repositories. However, non-traditional learners often find these sites difficult to navigate and use. This is frequently the experience of staff that support potential learners. From the latter there is a common cycle of responses. Initially there is excitement at the range of free resources available. However, the lasting experience is less positive and seldom leads to engagement and use of resources.

It’s common for individuals to report that resources are presented in formats that are distanced from their own experience. Frequently we’ve heard remarks like ‘it looks like a university and that’s not where I feel I should be’.

For individuals, and those who support them, the sheer number of courses available can be daunting. The difficulty of making choices combined with uncertainty about the value of existing skills, and whether new skills are needed, represents a barrier to engagement.

Dispositional factors can form major barriers to participation. For example, conceptions of education, and expectations of online study provide powerful disincentives to study. Individuals, and the organisations that support them, often default to a view in which learning in a class room with a teacher is the norm. Other models are seen a poor replacement. In addition, learner expectations are shaped by real experience. Online ‘study’, through mandatory tick-box, online training modules, is almost ubiquitous across the public and private sectors. These modules are universally hated and colour perceptions of learning in a negative way. In general, online is viewed as an individualised, isolated and second best learning experience.

Section 2: Overcoming barriers to participation

Introduction

Open education was initially concerned with learning resources (OER) and the freedoms enabled by open licenses. Increasingly, however, attention has shifted to the pedagogical practices (OEP) that support effective learning through the medium of OER. In this section we explore what OEP looks like in the context of supporting transition into and through formal education for non-traditional learners. The suggestions for good practice link back to the barriers outlined in Section 1 and focus on important issues that need to be addressed in facilitating or organising learning opportunities. In particular we look at how opportunities for peer support and interaction can be provided. It is important to stress that not all of the ideas identified here are either possible or appropriate in every context. The OEPS project is producing reusable resources and guides that support good practice in the areas identified in this section.

Learning design

This is really the first step. If you are working in a college, university or an organisation where you are part of a team it’s worth getting colleagues, and if possible students, together to work through the questions we note below. If you don’t have a lot of support around you it’s still helpful to think about the issues we identify and you may well be able to involve the potential students in the process. Some of the questions may seem obvious but it’s worth making them explicit. Important things to think about are:

![]() Who are the

students?

Who are the

students?

![]() What skills and

experience do they bring with them – in particular how familiar are they with

working online?

What skills and

experience do they bring with them – in particular how familiar are they with

working online?

![]() What are the

characteristics of the group – is it possible for them to get together face to

face and is there somewhere where they can do this?

What are the

characteristics of the group – is it possible for them to get together face to

face and is there somewhere where they can do this?

![]() Are there more

experienced individuals in the group who could help share their knowledge?

Are there more

experienced individuals in the group who could help share their knowledge?

![]() What do the

students want to get out of completing the course? Is some form of recognition important? If so its important the course includes

assessment that leads to a digital badge, certificate or even formal credit.

What do the

students want to get out of completing the course? Is some form of recognition important? If so its important the course includes

assessment that leads to a digital badge, certificate or even formal credit.

Whether you work through these questions in a group with colleagues or through discussion with students its worth logging your conclusions and any decisions you’ve made.

There is a customisable template for a Learning Design Workshop in the OEPS Legacy Resources.

Identify resources and making choices

Having analysed student needs you now need to identify OER that meet them. It’s unlikely you’ll find the perfect course but there are likely to be options that are good enough for your needs. You need to check the appropriateness of:

![]() The learning

outcomes

The learning

outcomes

![]() The level of

the course

The level of

the course

![]() The assessment

The assessment

![]() The course

structure and length

The course

structure and length

If you are part of a team with appropriate resources or skills it’s possible to edit and contextualise OER for your students. In the near future as software tools linked to OER repositories become more user friendly this will become an important and viable option. Currently, however, it still involves significant inputs of time and expertise. A much more straightforward option is to use the material as is. But, and this is really important, don’t just give the students the URL and expect them to thrive.

Curation

Students need information about the context of the course; for example, the origin of the material, how to access it, the level, time commitment and outcomes. If you have the capacity to reversion the material this information can be integrated into the course. However, if you using found material without alteration then you do need to explain all of this. How you do this, whether through written briefings, social media or face-to-face discussion depends on your context and circumstances. Essentially if the course content is good enough then you can make it your own through wrap around support that is sensitive to the needs of your learners.

Structuring opportunities for peer support

Many students approach online learning thinking that they face an individualised and lonely experience. They may also believe quite strongly that ‘proper’ learning takes place in classroom with a teacher who ‘delivers’ course content. It’s important to explain that there are alternative models. In particular, well-structured online materials allow versions of the ‘flipped’ classroom, where students study individually with the materials and then come together to discuss, question and debate. Some students will, from choice or necessity, study alone. However, individualised study is a tough option for non-traditional students and there are significant advantages in designing simple opportunities for working as a ‘group’. Group size has practical implications for how you choose to organise, but the key factor is that whatever arrangement is decided upon allows opportunities for social interaction, whether face-to-face or online. Critically the structure must allow students to communicate support each other in ways that are compatible with the circumstances they are studying in. There are a range of possibilities from weekly face to face sessions facilitated by someone with a professional teaching role through to a small number of meetings distributed throughout the study period and self-organised by the group. In some cases face to face meetings may not be possible and can be replaced by telephone conference calls, group Skype sessions or even a closed Facebook Group.

Whatever the circumstances three elements of structure are critical.

![]() An initial

‘induction meeting’ at which students can share worries and expectations and

make sure that there is a common understanding of how they will keep in touch

during the course. If possible

it’s good for everyone to get online and work together to explore the overall

structure of the course and how it’s possible to navigate through the different

components. Participants can share

ideas, experience and skills at this point.

An initial

‘induction meeting’ at which students can share worries and expectations and

make sure that there is a common understanding of how they will keep in touch

during the course. If possible

it’s good for everyone to get online and work together to explore the overall

structure of the course and how it’s possible to navigate through the different

components. Participants can share

ideas, experience and skills at this point.

![]() Setting

short-term targets within the overall context of the course. Simple stepping-stones that incorporate

opportunities for reflection, discussion and interaction with peers make it

much more likely that students will stay the course. Sometimes the course structure will

provide obvious places for this activity but it’s important to ensure that the

frequency and nature of these opportunities matches what participants are able

to work with.

Setting

short-term targets within the overall context of the course. Simple stepping-stones that incorporate

opportunities for reflection, discussion and interaction with peers make it

much more likely that students will stay the course. Sometimes the course structure will

provide obvious places for this activity but it’s important to ensure that the

frequency and nature of these opportunities matches what participants are able

to work with.

![]() Finally when

the course is finished many of the participants will feel much more confident

about their ability to undertake a structured course of study. This is a good time for the group to

share ideas about possible next steps.

Finally when

the course is finished many of the participants will feel much more confident

about their ability to undertake a structured course of study. This is a good time for the group to

share ideas about possible next steps.

Useful Links

The OEPS legacy collection has exemplar courses, case studies, reports, resources and briefings: www.open.edu/openlearncreate/oeps

Further Reading

On WP barriers

Cannell, Pete; Macintyre, Ronald (2017) Free open online resources in workplace and community settings–a case study on overcoming barriers, Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, Volume 19, Number 1, pp. 111-122(12)

Fuller, A., and Paton, K. (2008) ‘Barriers’ to participation in higher education? Depends who you ask and how’, Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 10, 2: 6-17

Gorard, S., Smith, E., May, H., Thomas, L., Adnett, N., and Slack, K. (2006) Review of widening participation research: Addressing the barriers to participation in higher education. A report to HEFCE by the University of York, Higher Education Academy and Institute for Access Studies

Stone, C. and O'Shea, S.E. (2013) Time, money, leisure and guilt-the gendered challenges of higher education for mature-age students’, http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1193&context=sspapers

Digital Exclusion

White, D. (2013) Across the Divide: Tackling Digital Exclusion in Glasgow, Dunfermline: Carnegie UK Trust

OER, OEP and open licences

Becoming an Open Educator is a short open course that provides a useful introduction to the ideas and concepts involved.

Download this report as a document or as a