1 Competing views of school

This course is premised on a belief that we can all take actions within our everyday working lives which contribute to the overall development of equality, participation and inclusion. However, if we wish to explore how to play a leading role in the delivery of inclusive education we have to begin with our understanding of what it is that the education system is trying to achieve. This echoes ideas from a study in Denmark (Thingstrup, Schmidt & Andersen, 2018) which explored how two different groups of educators worked together. One group was largely concerned with qualification (particularly pupils’ academic performance and attainment), the other group focused on broader pedagogic aims that could be seen as more directly related to socialisation and the uniqueness of the individual. Working to achieve competing school goals involved an ongoing negotiation of meaning, a struggle over power, where people took up different positions and adopted different practices dependent upon what was possible (or not) in their particular setting. The researchers concluded that if these people wanted to work together in ways that achieved the intended goals of legislation, they needed to have the space to develop common ground and to explore what they could achieve together.

Many people speak of schooling as if it has some universally understood and agreed values. It is situated, for example, in numerous international conventions and within many countries’ legislation associated with gender, disability, race, equality, rights and ‘the exasperated etc’ (Butler, 1990 p. 143). Consider this quote:

The reasons for providing all the world’s children with high-quality primary and secondary education are numerous and compelling. Education provides economic benefits and improves health. Education is a widely accepted humanitarian obligation and an internationally mandated human right. These claims are neither controversial nor new.

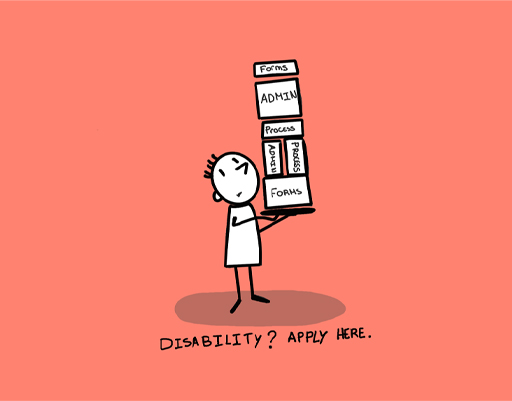

However, despite such claims, delivering education based on equality for all people is neither universal nor historically significant, and it continues to compete with a range of other functions (see Table 1).

| Country/Region | Some of the driving forces |

|---|---|

| France | Trying to control a powerful catholic church. |

| Prussia | Supporting the development of the protestant faith. |

| Scandinavia | Supporting the development of the protestant faith. |

| Japan | Developing industrial and military competitiveness; reorganising national institutions; creating national solidarity, a central bureaucracy, a skilled labour force and a future elite. |

| Soviet Russia | Developing a literate nation; establishing meritocracy and the basis for industrial development. |

| Ecuador | Overcoming parental disinterest and colonial gender bias. |

| Arab states | Aiming to redress gender disparities. |

| Spain | Aiming to unify geographically and culturally distinct regions. |

| Sri Lanka | Aiming to reduce child labour. |

| India | Aiming to build the nation. |

Educational expansion has been an uneven process, with vested political interests having to create educational wholes out of ‘diverse, semi-related, and often non-existent parts’ (Benavot, Resnik and Corrales 2006, p. 4). The impact of respected educational thinkers has been far less influential in initiating education than broader social, political and economic pressures. These social, political and economic processes created administrations which brought together competing interests and loyalties. The mix of priorities and interests meant that the focus of these processes was often not primarily upon what we might now think of as educational targets.