3 Thoughts on difference

At the heart of inclusion are our attitudes; in particular (in the complex, diverse world of education) the attitudes which inform our responses to what might be seen as difference. This is because our understandings of difference are central to how we understand and evaluate ourselves, our social situation and our life experiences. The ‘self’ arises as a result of social processes of which we are part. Our sense of who we are is aligned to the reactions of others (Mead, 1934; Cooley, 1962; Becker, 1963). We judge ourselves against the ‘other’ beyond our boundaries; as a consequence, boundary setting is a key dimension in defining and giving meaning to ourselves and our society (Vislie, 2006). The ‘other’ has a broad range of meanings. For Hat Rosenthal (2001) it means any other person. Edward Said (1978) identified how for the ‘the West’ ‘the Orient’ had been a site of contestation, colonisation and cultural resource, and its most enduring image of the other. Simone Du Beauvoir (1949) suggested:

The category of the Other is as primordial as consciousness itself. In the most primitive societies, in the most ancient mythologies, one finds the expression of a duality – that of the Self and the Other. This duality was not originally attached to the division of the sexes; it was not dependent upon any empirical facts. … Thus it is that no group ever sets itself up as the One without at once setting up the Other over against itself (p. xxii–xxiii).

Du Beauvoir noted that identifying the other was usually about the majority imposing ‘its rule upon the minority’ (p. xxiv). She then went on to question this observation by saying it did not apply where women were concerned; but othering also allows the values and ideas of a minority of nations and elites within them to dominate policies and practices. The other is therefore not just to be seen as someone who is not me or a minority, but it is more generally associated with those who are being discursively positioned as being in some way inferior or dangerous or marginal or outside.

When thinking about the ways in which we other people (and how this might influence relationships with all members of a school community), it is helpful to consider how you view difference. Avtar Brah (1996) talks about four ways in which difference can be conceptualised:

- Experience – lived relationships as we perceive them.

- Social Relations – the cultural and historical circumstances and practices producing the conditions from which group identities and shared narratives form.

- Subjectivity – how you make sense of your relationship (your subject position) with the social, cultural and physical environment.

- Identity – your sense of self, a ‘self’ that is situated in a multiplicity of social situations, and is required to present/understand its ’self’ in different (and frequently contradictory) ways.

In this short course it is not possible to explore these issues as broadly and deeply as you might wish; but it should give you the opportunity to explore ways to understand views on difference and people’s experiences of difference.

Activity 5: A different difference?

Read the short article: Thinking Differently About Difference [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] (Martin, 2012) (The Open University is not responsible for external content.)

As you are reading consider particularly what is meant by the three models she proposes for thinking about difference:

- Sameness and difference in binary terms.

- Sameness-difference understood as aspects of diversity.

- Difference-sameness understood as relational.

Then consider how these models might play out in the context of Brah’s 4 conceptualisations of difference (Experience; Social Relations; Subjectivity; Identity). Can you think of examples from your own life and how the models might apply for them? For example, where a binary view of sameness and difference has produced a particular life experience or shaped social relations.

When you have finished this task you may want to have a discussion with friends or colleagues.

Discussion

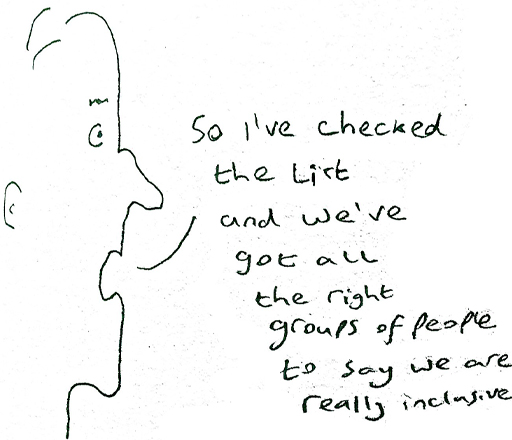

When carrying out this activity, you considered labels and where they would fit in relation to these models; after all we attach labels to children and colleagues which position them in all kinds of categories related to knowledge, skills, life experiences, personal characteristics, abilities and so forth. You could see the first model in play when labels are used to define people in binary terms, placing people in one group or another – making them insiders and outsiders. But we could also see the second model in action when labels have a role to play as an aspect of diversity; with the label perhaps being understood as one identity among many.

However, in both instances you saw how such a label might constrain how an individual experienced the social context of a school. The label could frame that person’s position in that context and therefore their sense of self and the role they played within the school community. You will hopefully have recognised that anything which encourages the practitioner to view the child in separation from the others risks separating them in practice, thus removing them from collective planning and collective learning opportunities. In contrast, holding the third model of difference would mean that labels themselves would be understood as social constructions and the characteristics and behaviours they described could be seen not as aspects of an individuals but as things that emerged from the relationships with which they were engaged.

It is this latter approach which reflects the views and values underpinning much of the literature associated with inclusive education and how systems can be transformed. In seeking to encourage and support the delivery of inclusive education, a key role everyone can play therefore is in disrupting categorical views of difference. These views position people as other, limit our understandings of each other and constrain our imagining of possible futures.

So, now consider some ways to disrupt our notions of difference and the categories you might use to understand that difference.

Activity 6: In the beginning

Stories can help us to understand why things are the way they are, how people feel about them and the nature of the actions which people have undertaken. Storytelling educates because it allows us to translate individual private experience of understanding into a more public culturally negotiated structure (Bruner, 1986). Stories can therefore be a powerful means of explaining and understanding the culture and biases of any institution, as well as providing a tool for disrupting preconceptions and challenging the status quo.

Below are three readings, with suggested extracts to focus upon. The first reading helps you to understand how telling stories about people and institutions can reveal new ways of understanding. The second story focuses upon the way counter-stories can reveal the day-to-day challenges faced in the school situation. The third suggests that counter-stories can be accessible representations used in a variety of ways.

As you read consider the ways the use of such stories could be a tool within the formal and informal moments of the school day to encourage change.

- Dornbrack, J. (2007) ‘Reflecting on difference: an intervention at a public high school in post-apartheid South Africa’, Journal of Education, 41(1), pp. 97–111. Start at: Disrupting stereotypes: focus group 8 (pp. 102–109). (The Open University is not responsible for external content.)

- Martell-Bonet, L., Parenti, T., & Perez, J. I. (2021) ‘Bravery Against Silence: A Composite Counter-Story of Minoritized Students’, Florida Journal of Educational Research 59, 1, pp. 136–149 . Start at: A Latinx Educational Journey (pp. 138–145). (The Open University is not responsible for external content.)

- Dadkhahfard, S. and Takeuchi, M. A. (2020) ‘Visual Counter-Storytelling Toward Equity and Teaching’. In Gresalfi, M. and Horn, I. S. (Eds.), ‘The Interdisciplinarity of the Learning Sciences’, 14th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS) 2020, vol. 4 pp. 2373–2374. Accessed from https://repository.isls.org/ bitstream/ 1/ 6566/ 1/ 2373-2374.pdf (The Open University is not responsible for external content.)

Discussion

Stories are not inherently positive. It is quite possible, as a result of deficit-storytelling, for people to internalise negative stereotypic images that more powerful groups have constructed through stories (for example, stereotypes about gender roles or characteristics associated with a type of impairment). Such cultural stereotypes can both suppress someone’s performance, their perception of their own abilities and other people’s views of their capabilities. However, counter-stories can work against this. They are powerful because they offer a lens for reviewing discrimination, prejudice, inequity, racism and intolerance. They make us question the everyday representations of people in the media, within policy, within paperwork or in our collective and individual understandings. They help people to explore and explain their oppression, and because they are stories, they are also readily accessible.

Stories also enable you to understand other people’s ways of doing things. They are a means to explore alternative ways of working, without having to develop a deep theoretical understanding or specialist knowledge base. A tale about who someone is, their interests and capacities, is a means to opening up possibilities; to offer new ways forward. It can provide a space for thinking about that person, the context they are in and the relationships you and others have with them. If you listen to a story, you are included; and by listening to someone tell a story you too are including them.

A challenge, perhaps, is how to enable counter-stories to be heard. Given the human love of telling tales, it is something people are likely to find rewarding, and they are relatively simple to share. Inevitably, there are ethical issues which may need to be resolved, but they can, for example, be formally collected and shared as a professional development or a curriculum activity. They are also something that can be easily engaged with and encouraged in far less formal circumstances.