I was shocked when I read that the country of my birth was thoroughly tangled up in racism (Pierre, 2013). Modern Ghana, I had thought, would have had no place for race. After all, it was the first country in Africa to declare its independence from British colonial rule in 1957, the year before I was born. But Ghana, it turns out, is divided along a colour line that prizes the lightening qualities of whiteness, a lightening that can determine access to jobs, higher incomes, prestige and position,just as it does in the UK. Perhaps it’s got something to do with the fact that morethan half the population of Black Africa live in countries where English is an official language (Appiah, 2004). Whiteness seems to be global in its power yet very personal in its meaning, invisibly forging a subjective sense of self and yet alsocapable of building geo-political alliances spanning history and continents.

Being born in Ghana I’ve always known I’m not Black but my Whiteness is not something I see easily in the mirror. If I look away from the mirror, I can see it in the story that took my Irish father and English mother to what was then called The Gold Coast to work in the colonial education service in the early 1950s. My birth certificate from Ghana’s capital, Accra, has the words ‘Gold Coast’ crossed out in several places and Ghana handwritten in ink above it. Follow the money, as the saying goes. That golden thread of whiteness breaks, unexpectedly, when I complete the ‘place of birth’ part of the application form to register for a PhD with the LSE in London in 2006. I get billed an astronomical fee as a foreign student, despite declaring my Irish nationality. ‘Accra, Ghana’ appears to have overridden the ‘Irish’ in the ‘Nationality’ box. And then the simplicity of the correction, my Whiteness restored, the fee reduced. The wages of Whiteness (Du Bois, 1935) is a useful concept here, but no one’s life is simply black and white.

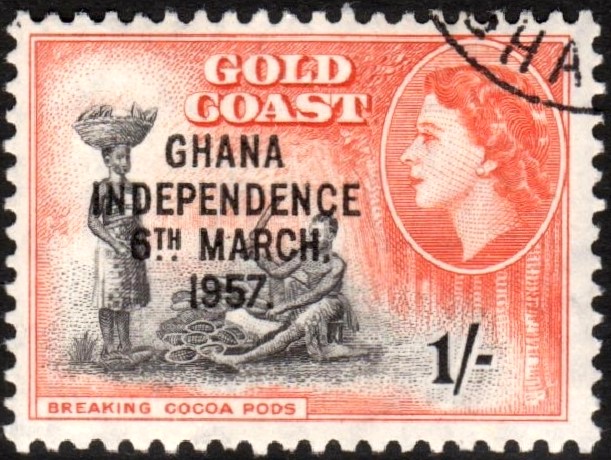

A postage stamp of Gold Coast overprinted for Ghanaian independence in 1957

A postage stamp of Gold Coast overprinted for Ghanaian independence in 1957

Revising his first conceptualisation of the ‘colour line’, Du Bois (1910) asserted the problem of the colour line was the problem of Whiteness, and Whiteness is complicated. I live with the accumulated benefits of an emergent class system that crossed the Irish Sea centuries ago, went beyond the Pale and spread across the globe (Linebaugh, 2019). In Africa, the Irish have always been unequivocally White even when to the English in England they have been a bit less than White, and possibly a bit Black (Ralston, 1999). It is some of these personal and political complications of whiteness that I explore autobiographically in this introduction so as to help establish the significance for criminologists of the pulse of Empire that flows so silently through our discipline. Our engagements with criminology are formed through events we have experienced directly but write about infrequently because they are considered ‘ultra vires’, out of scope for being intimate, private or domestic.

No imagination but the nation: Whiteness

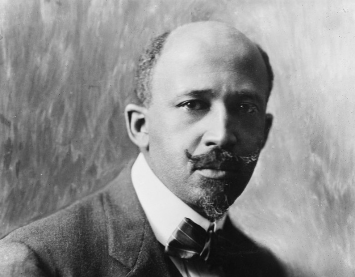

Phenotypical Whiteness and structural Whiteness are often conflated and regularly confused. What I see in the mirror is not causing divisions and hierarchies in one of the most iconic states of Black Africa, a country where W.E.B. Du Bois is buried, that provided a home to Maya Angelou and that made Frantz Fanon a government minister (James, 2012). The Whiteness bringing this division and hierarchy to Ghana is functional to the structure of racial capitalism that survives the colonial period.cGhana is no one’s Gold Coast anymore thanks to Osagyefo Dr Kwame Nkrumah, but the dreams of his generation of African leaders remain unfulfilled, frustrated by Cold War manoeuvres (Sherwood, 2019; James, 2012) and the obduracy of racial capitalism.

In the twenty-first century, Whiteness is assuming a mutely belligerent pose against the dawning realisation that the old martial rules of colonialism, ‘Whites rule, non-whites are ruled over’, no longer apply. This comes from a recognition that globalisation implicitly ‘provincialises’ Europe from its erstwhile pre-eminent position as the central and defining colonial force of the planet (Chakrabarty, 2000). As a result, the political alliances of Whiteness have entered an unsteady state which brings them more into view and closer to personal experience. The phenotypical Whiteness of past and present prominent political figures, such as Boris Johnson, Donald Trump, Nigel Farage and the British royal family recognisably aligns with the structural Whiteness of their political projects to make both profoundly unsettling.

The British Royal Family at Trooping of the Colour.

The British Royal Family at Trooping of the Colour.

Asking what we understand by Whiteness is important because a central, founding principle of racism is the superiority of the White race, although this goes largely without saying (among White people). As James Baldwin (1998, p.122) points out ‘…there is a great deal of will power involved in the white man’s naïveté’. Making explicit reference to whiteness challenges the disavowal of race as a prevailing, defining but unspoken feature of white identities (Garner, 2007). This disavowal can only be disingenuous because for most of the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries the idea of Whiteness was completely mainstream. It was essential, foundational and integral to the major political powers of Europe and the USA. Race was the language of international politics and domestic policy, openly and extensively referred to as an ordinary fact of life. Races, just as much as states or nations, were seen as one of humanity’s foundational political units and were spoken of as such (Vitalis, 2015; Lake and Reynolds, 2008). The history of all the various nation states from north America, western Europe, southern Africa and Australasia were underpinned by racial ideas that licensed genocide, dispossession, exclusion and slavery. White frontier masculinities were valorised as representing and embodying the new democratic and utopian spirit of the age, ‘liberating’ all that came into their Imperial path. Race offered a theory of human hierarchy that licensed the brutality and violence involved in excluding from the fully human all those who were not fully White. The expansion of Euro-imperialism from 1884–1914 – sometimes referred to as the scramble for Africa – could not have been accomplished without it.

The political implications of replacing the theoretical engine of race with social constructionism did not reverse the historical momentum of race because it has never been primarily propelled by scientific justifications.From Australia to the United States White men talked (and wrote) at great length and with great conviction, about themselves as a race, as ‘white men’ building countries for other ‘white men’ (Lake and Reynolds, 2008). This is not a semantic accident or a kind of vernacular innocence. Whiteness, and ideas about the White race, were as explicit as they were central to such forms of transnational community. Whiteness was a widespread, self-styled form of transnational racial identification, an explicit and deliberate mode of subjective identification that crossed national borders and shaped global politics. It has only relatively recently lost its voice and come to be seen as the defining characteristic of political extremism, the atavistic trademark of the political fringe. This political laryngitis silences its historical and political ubiquity and removes the conceptual handles that might allow us to bury it properly. It was only in the second half of the twentieth century that the grip of White supremacy began to be loosened and the widespread subjective identifications that propelled it through history became gradually less tenable and less publicly endorsed. This followed the defeat of fascism in Germany and the 1948 UN Declaration of Human Rights which repudiated ‘race as science’. However, the political implications of replacing the theoretical engine of race with social constructionism did not reverse the historical momentum of race because it has never been primarily propelled by scientific justifications.

The Second World War finally, undeniably, exposed the horrific consequences and intrinsic violence of racism to European societies and sensibilities. Nevertheless, Aimé Césaire condemned white Europeans’ complicity in the rise of Nazism as ‘they tolerated Nazism before it was inflicted on them…because, until then, it had only been applied to non-European peoples’ (Césaire, 1972, p.14), whilst Frantz Fanon described Nazism as ‘a colonial system in the very heart of Europe’ (Fanon, 1967, p.33). The legacies of the defeat of fascism are post-colonial but their implications for contemporary anti-racism remain contested and profoundly unresolved as Susan Neiman (2018) makes clear in her provocative juxtaposing of post-slavery USA and post-war Germany. Nowhere is this more obvious and problematic than in the disintegrating political consensus and infrastructure of the United Kingdom. The truth is that nobody’s ways of being in the world are innocent of race, least of all white people’s in Britain. Nobody’s imagined community, their nation or any other form of fellow feeling is free of race.

Criminology’s poltergeist and Europe’s Whiteness

Black Caribbean pupils are more than three times more likely to be permanently excluded from school; those who identify as Black or Black British are four times more likely to be stopped by the police than their White counterparts...Few people will defend racism but many people continue to misunderstand and underestimate it. Whiteness operates as a form of collectively maintained ignorance for which there are a number of alibis to cover the way White people benefit from the subordinate status of Black people. One of these is that racism is simply an individual moral failure, a flaw of personality or character rather than an economic, extractive, exploitative social relationship. Race, according to Avery Gordon (2008), is a haunting presence in our personal lives and social relations because its effects are everywhere felt but nowhere specified: the machinery moves while the engine ise declared dead. Black Caribbean pupils are more than three times more likely to be permanently excluded from school; those who identify as Black or Black British are four times more likely to be stopped by the police than their White counterparts; and in 2016 for young people aged between 16 and 24 years, the White ethnic group had the lowest unemployment rate of 12%, a figure which more than doubles when it comes to young people of Black (25%) and Bangladeshi/Pakistani (28%) backgrounds respectively (Nayak, 2018). These patterns that recur throughout the social structure indicate that even as race becomes a discredited concept it continues to structure society. From segregated housing to selective criminal justice, race is experienced like a poltergeist – objects are moved by an unseen, inexplicable force for malign, life-limiting and unsettling effect.

The neglect of the way race produces tangible results from intangible sources restricts the development of ways of resisting and challenging its toxic social presence. Criminological scholarship needs better tools to bridge the gap between the ontological subjectivity of race and its epistemological objectivity; tools that can account for the way it appears as a solid ‘social fact’ in our work, but then disappears as a ‘social fiction’ from our personal lives. As is often the case, Stuart Hall put his finger on it when he reflected on how Marxism morphed into cultural studies in the Birmingham Centre for Cultural Studies in the 1980s:

We had to develop a methodology that taught us to attend, not only to what

people said about race but… to what people could not say about race, it was

the silences that told us something; it was what wasn’t there, it was what was

invisible, what couldn’t be put into the frame, what was apparently unsayable

that we needed to attend to

(cited by Rodman, 2006, in Smith, 2016)

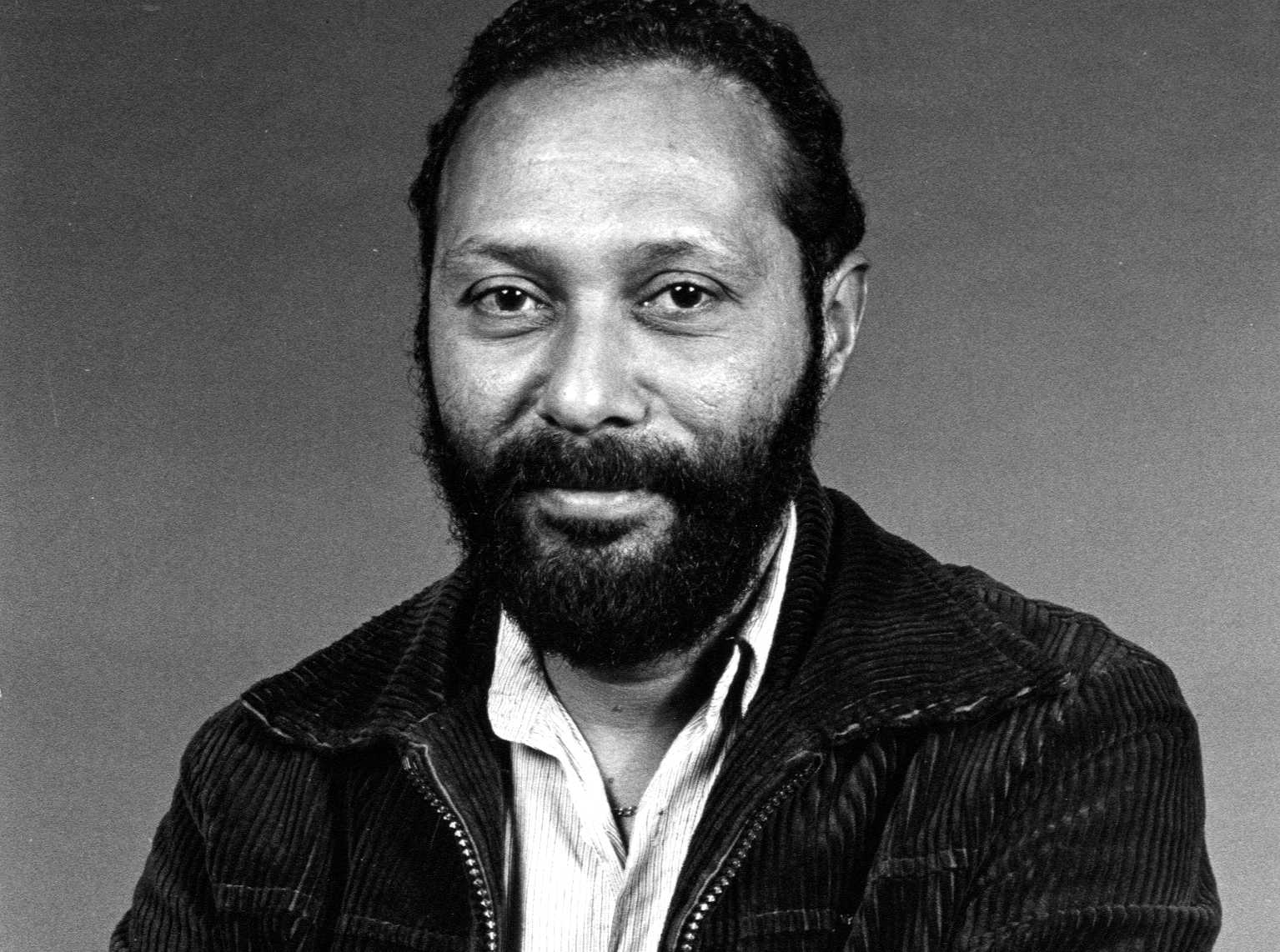

Portrait photograph of Stuart Hall (1932-2014), Professor of Sociology from 1979 to 1997

Portrait photograph of Stuart Hall (1932-2014), Professor of Sociology from 1979 to 1997

Making race and racism more intelligible involves the generation of narratives that can displace this functional silence, limit the productivity of the ‘invisibility’ of race. This narrative potential is radically under-developed in UK criminology (Phillips et al., 2019). What spaces and places are there for focusing on and discussing race in criminology, what special conferences are held, what symposia are convened, what journals are launched, what Special Issues are curated, what teaching curricula are adopted or developed that address the recurring, resilient and pervasive presence of race and its mysteries? Unlike in sociology, and despite the proliferating subdisciplines of criminology, these have hardly developed at all within British criminology. This seems like wilful neglect or careless indifference to Stuart Hall’s warning that ‘it is only as the different racisms are historically specified in their difference – that they can be properly understood’ (Hall, 1980, p.337). Without these specifics in the UK, the prevailing criminological understandings of race and racism risk becoming derivatives of, and defer to, the monstrous scale of the US experience of race, sheltering behind its grotesque penal brutalities (Phillips et al., 2019). Exposing and condemning American racism tends to reproduce a deep-seated and longstanding habit of minimising and obscuring racism in Britain by contrasting it to the US, even when its racial disparities in criminal justice are greater than in the US.

Getting Africa in the house

James Baldwin (1998, p.122) offers a few clues as to how we might begin, so late inthe day, to look into our European souls to find an answer:

For the history of the American Negro is unique also in this: that the question of his

humanity, and of his rights therefore as a human being, became a burning one for

several generations of Americans, so burning a question that it ultimately became

one of those used to divide the nation. It is out of this argument that the venom of the

epithet Nigger! is derived. It is an argument which Europe has never had, and hence

Europe quite sincerely fails to understand how or why the argument arose in the first

place, why its effects are so frequently disastrous and always so unpredictable, why

it refuses until today to be entirely settled. Europe’s black possessions remained,

and do remain, in Europe’s colonies, at which remove they represented no threat

whatever to European identity. If they posed any problem at all for the European

conscience, it was a problem which remained comfortingly abstract: in effect, the

black man, as a man, did not exist for Europe. But in America, even as a slave, he

was an inescapable part of the general social fabric and no American could escape

having an attitude toward him.

Stuart Hall, lucid as ever, picked up on Baldwin’s critical insight that White Europeans might have dodged the bullets that criss-cross the American racial divide, but they provided the guns and ammunition. Hall’s evocation of the condition of ‘being in, but not of, Europe’ (Hall, 2003) is richly suggestive of the proximities Europe’s white people regularly refuse. Those proximities need a narrative thread as surely as any social fabric (Anderson, 2018) and White people in criminology, such as myself, have to start somewhere, and perhaps with ourselves.

Rate and Review

Rate this video

Review this video

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Video reviews

Daniel Linehan - 4 February 2021 10:39am

I find it perverse that the Open University is so keen to divide everyone up along racial lines and, long after the successes of Liberalism, to once again try and make Black Britains feel like they are outsiders in their own country. The gnawing self doubt felt by the author is appropriate, he is truly privileged by his birth, but to suggest that he couldn't get funding for his course because of his 'Ghanaian heritage', only for it to be reversed when they discovered he was white is to misrepresent the facts. It is the hard fact of nationality, distinct from the invented characteristic of race, which determined his entitlement to funding, something which can be witnessed by any British person of any race applying to study at a Higher Education institution today.

I would invite the Open university to appeal to the shared characteristics held by every student at the university, characteristics like honest intellectual enquiry, as a way of uniting us all in the improvement of ourselves and our society. Instead it seems rather more intent on dividing everyone by skin tone at the whim of a race obsessed old white dude.

Suki Haider - 7 February 2021 1:03pm

Hi, your point, that talking about whiteness could establish whiteness as the norm, and non-whites as other, is what the racial concept of Whiteness refers to. The article introduces the invisibility of Whiteness as social construct. I recommend that you read Reni Eddo-Lodge, ‘Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race’ (2018). She explains the power of Whiteness and its consequences in Britain today.

I interpreted the article differently. I found the author’s succinct account on his lived experience pertinent to his argument. Education, at all levels, is a function of society and it should reflect the diversity of society. I do not see publishing the article as a token gesture by the Open University, nor do I find an attempt to divide along racial lines. European universities have a shameful past. It was here that race theory was born and the stereotype that white people were superior given intellectual backing. It is good that universities now recognise the impact of what they teach and how they teach on social cohesion. This is a result of student action in campaigns such as Rhodes Must Fall and Why is my Curriculum White?

It is important that criminology students learn about the injustices perpetuated against Blacks in the criminal justice system. These are not inequalities shared by white people. The responsibility of educational institutions to represent cultural diversity was recognised by the Department of Education in response to the MacPherson inquiry (1999) into the murder of Stephen Lawrence, which described the police response to the victim and his family as ‘institutionally racist’.

To address the injustices of racial inequality evident in criminology, and elsewhere, we must be prepared to talk openly about the impact of race and racial stereotypes. Talking about race is not to dismiss the existence or impact of class inequalities, they both shape lives. There is a willingness by the media, politicians and indeed educators to acknowledge the impact of class on life chances, but they are often squeamish when it comes to race. I hope the OU publishes more articles on hierarchical systems of power.

Daniel Linehan - 21 February 2021 11:45pm

I disagree with you. There isn't a willingness to discuss class amongst politicians, because the current fixation on race is sucking all of the air out of the room. Politicians, and administrators in general, would far rather have a discussion about race because they can point to an MP like Kwasi Kwarteng as a successful black tory, but ignore the fact that he went to Eton. They dodge the question of the fundamental disadvantages for those educated by the state. The sad fact of the matter is that an effort to help the working class would help underprivileged kids of all races, but we aren't even asking the right questions.

The Rhodes must fall campaign, which you identify as doing positive work, is in my opinion a waste of energy, representative of a bourgeois and decadent student body. If the students of Oxford really wanted to make a change which affects the people of this country, they would be asking why their university admits so few state school educated undergraduates.

As for the notion that reracialising the academy is the best way of countering the historical crimes of the European universities of the past, I'm sorry but I find it risible. The only way we can eliminate racism is by more racism? I've tried fighting fire with fire; you get fire.

Daniel Linehan - 4 February 2021 11:03am

I'm not sure if it is important for white people, or anyone, to talk about whiteness. I don't even know what whiteness is. Could anyone help answer my questions, I have loads.

Doesn't it centre white people if we talk about whiteness and establish them as a norm and everyone else as the other? Isn't that what we're trying to get away from? If we problematise whiteness then aren't we portraying white people as a problem? How do we solve the problem of whiteness? Can we exclude white people, or does the problem of whiteness persist? If people of colour populate a white structure, does that eliminate the whiteness of that structure, or does it mean the people of colour are manifesting whiteness? Is the problem of whiteness a power imbalance? Is it that the hierarchies in this country consist of different orders of people, with the top rank having the most power and the bottom rank having the least? Is it possible that the whiteness described is actually a description of the class system, and that we need to be discussing class and not skin tone?

Should the students of the Open University be more questioning of an administration which wants to divide us up along racial lines and make empty gestures about diversity and inclusion to disguise their own complicity and privilege and to protect their jobs?

Is the above post one of these empty gestures, and a visible manifestation of racism from a higher education authority?

Anyone else sick of being divided up into arbitrary groups?