There is a general consensus that listening to children and young people is important. Recent developments in research, practice and policy, such as those from the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, 1989), call for greater levels of child and youth engagement. Participation is a word we often use to describe the active involvement of children and young people in communicating their views. Yet participation means more than merely listening. Not only do children and young people have a basic human right to express their views on matters which are important to them, but also that their views are taken on board by adults and used to improve young people’s lives.

There is a general consensus that listening to children and young people is important. Recent developments in research, practice and policy, such as those from the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, 1989), call for greater levels of child and youth engagement. Participation is a word we often use to describe the active involvement of children and young people in communicating their views. Yet participation means more than merely listening. Not only do children and young people have a basic human right to express their views on matters which are important to them, but also that their views are taken on board by adults and used to improve young people’s lives.

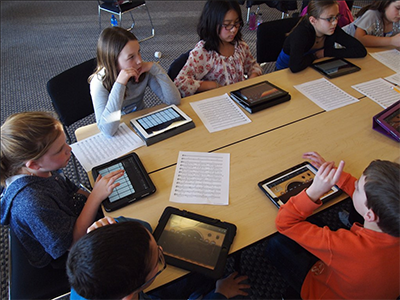

Children and young people can participate in different ways. They can sit on school councils as a way of representing the views and experiences of their peers, for example. They can volunteer within their local community and contribute to advisory and policy working groups, like Ellie Jones who we have interviewed about her experiences with the Diana Award. In addition, children and young people can design and carry out their own research as a way of informing local community and national policy and practice. Our research at the Open University’s Children’s Research Centre focuses on different aspects of participation in education, health and social care (for example Kerawalla’s 2014 research exploring participation through inclusive inquiry). Whilst we are fully committed in promoting diverse approaches to participation, we also take a critical approach. As a concept, participation is complex, rarely questioned within a critical arena and often tokenistic in practice. Discussions on participation are synonymous with many claims - from providing opportunities for personal and social growth, learning and development, to basic human rights and democracy. Yet our research shows that this all too often this glosses over complex experiences.

Adults know best

Kellett (2009, 2014) describes how children and young people have traditionally been denied the right to participation, and how this perspective has more recently been challenged by researchers, practitioners and policymakers who argue that even young children have important things to say and that their views can help improve services. There can be no denying children and young people’s basic right to be listened to - yet participation provides no guarantees. Our research indicates that often only certain types of children and young people choose to participate in research activities and volunteer projects and these choices are not necessarily democratic or equitable (Bucknall 2012, 2014). To some extent, participation relies on a child or young person’s skills, abilities and confidence in taking the initiative. Participation can also be offered by adults as providing a learning opportunity or a means to enhance confidence. These different ways of promoting participation are couched within an ‘adult knows best approach’ which is somewhat at odds with democratic ideas around participation.

Participation and power

Participation is often presented as a way of addressing power relations between adults, children and young people, and often promises to make a difference in this area (Cooper, 2014). Despite a host of developments which now recognise and value children and young people’s contributions, participation often falls short of making a difference to the power balance (Montgomery, 2009). Children and young people are regularly consulted and listened to - but many report frustration when they feel that contributing their views does not ultimately make any difference or improve their lives. Adults intervene on final decisions and the representation of children and young people’s views continue to be translated and often censored.

Resistance

As adults we sometimes assume that children and young people want to participate. Yet our research demonstrates that many children and young people appear to resist participation. It is not clear whether these children or young people want to participate but do not have the confidence, skills or competency through which to pursue this option or whether they prefer not to share their views. Can resistance also be considered as a form of participation? – exercising one’s right to remain silent? The issue of participation is not straightforward.

Despite such a complex picture, participation continues to represent some sort of gold standard for policy, practice and research within the field of childhood and youth studies. Our research at the Children’s Research Centre continues to examine the complexities, to critique different approaches and to consider the varied ways in which we listen to (and don’t listen to), engage with, and work with children and young people.

References to all citations can be found on the Children's Research Centre website

Watch an interview with Ellie Jones, a young person who is an advocate and role model for youth participation.

If you'd like to learn more about children and youth studies, explore more about participation on Openlearn, or study free courses with the Open University.

What do children and young people think about parenting issues?

- Can we make our kids clever? - take the poll

- What do children and young people think? - see the results

- What is the best way to parent through separation? - take the poll

- What do children and young people think? - see the results

- How do you get kids to behave? - take the poll

- What do children and young people think? - see the results

- Join in the debate

For more information on the Radio 4 programme, Bringing Up Britain, see the series page and episode guide here.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews