This content is associated with The Open University's Psychology courses and qualifications.

You see your partner, your friend, your colleague, your neighbour every day, but the moment you try to describe their face, you find yourself awkwardly falling into generic descriptions like “dark hair (dark brownish?), two eyes (brown I think), a mouth a bit full and under the nose which is slightly bigger than average”. Surely, you should be able to do better than that! Don’t despair yet! You are not alone and your partner will not hold it against you (probably). At least you correctly remembered that their mouth is under their nose (although they may want to have a talk with you about the “slightly bigger than average nose” comment). The thing is that we are not that good at remembering and describing faces. To make things bleaker, we are even worse at remembering and describing faces of unfamiliar people.

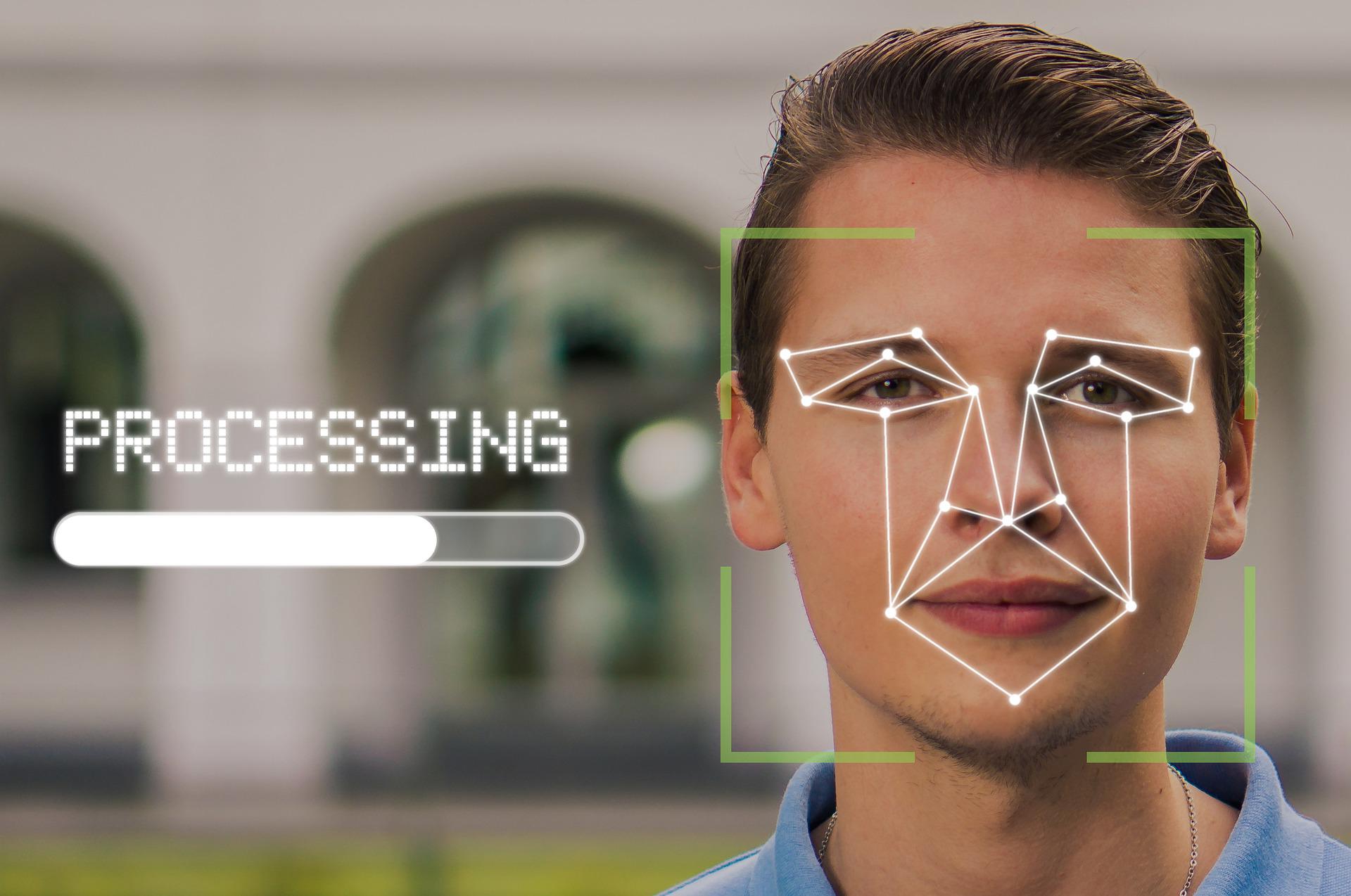

Despite being bad at remembering faces and developments in forensic science, police continue to heavily rely on eyewitness testimonies to identify a perpetrator (in other words, on our perceived ability to accurately recall and describe the face of someone whom we have never met before and only encountered under unique circumstances). The conduct of identification procedures is based on the concept of an impartial witness, who is clear that the perpetrator may not be present in the identification parade, who feels under no pressure to select someone and, if they do select someone, does so because they recognise that person as the perpetrator. However, psychological research has revealed the risks of relying on such testimony and how careful the police must be when questioning witnesses.

Why should that matter to people?

Members of the public could get involved in police investigation procedures either as suspects or witnesses who have experienced an event and might be able to relay information relevant to it. Burton, Evans and Sanders (2007) found that the number of witnesses identifying themselves as vulnerable are bigger than what the “” document had concluded. This means that vulnerable witnesses are not a minority group, but also implies that identifying vulnerability and planning appropriately could be a challenging task.

This can be particularly true for eyewitnesses on the autistic spectrum. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a developmental disorder which is characterised by impairments in communication and social interaction, sensory difficulties and repetitive patterns of behaviours, activities or interests. Furthermore, people with ASD process faces differently than a neurotypical individual meaning that they tend to focus less on and give fewer details about a face or a person. Additionally, they have difficulties remembering what happened during an event, who did what and generally putting the pieces of an incident together. These difficulties could compromise the quality of evidence ASD eyewitnesses give to the police.

Why is this important?

Eyewitnesses with high functioning autism (on the milder end of the spectrum) are represented in the Criminal Justice System as victims, witnesses or perpetrators. However, they may not be immediately recognisable to police officers. There is an important question relating to the reliability of autistic individuals who are witnesses in a forensic setting. Studies have shown that people with ASD can act as reliable witnesses, but they may be more reliant on prompts and cues to help them accurately recall faces and events. There is evidence to suggest that there is added benefit in allowing eyewitnesses with ASD to create their own visual cues to support recall of faces and events.

Therefore, understanding their abilities in terms of their memory functions, how they may impact on their ability to recall an eye-witnessed event and how professionals in the Criminal Justice System can devise ways to best interview them, is essential.

Working with ASD eyewitnesses could be stressful to police officers as well, as they are the first to interact with witnesses that could require special assistance and therefore it is important to be able to recognise them.

Dionysia's PhD

My PhD is looking to:

- Better understand the issues that individuals with ASD have with face processing, the eyewitness identification process and the implications that this may have on identification procedures.

- Explore police officers’ perceptions, knowledge and understanding about autism and ASD witnesses, their perceptions regarding identification processes and their effectiveness when used with vulnerable eyewitnesses.

In this project the aim is to use data from a questionnaire survey with police officers and senior officers, as well as data from the ASD community exploring their perceptions of interacting with the police, so I can identify areas of police practice where improvement might be needed and develop and test operational procedures to improve police practice during the identification process.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews