10 The legacy of Mexican muralism

While the triumph of Kahlo’s reputation, both critically and commercially, may have been bolstered by the constellation of historical, political and intellectual forces sketched out in this course, the example set by the Mexican muralists does have an afterlife, if largely outside of the rarefied world of high art.

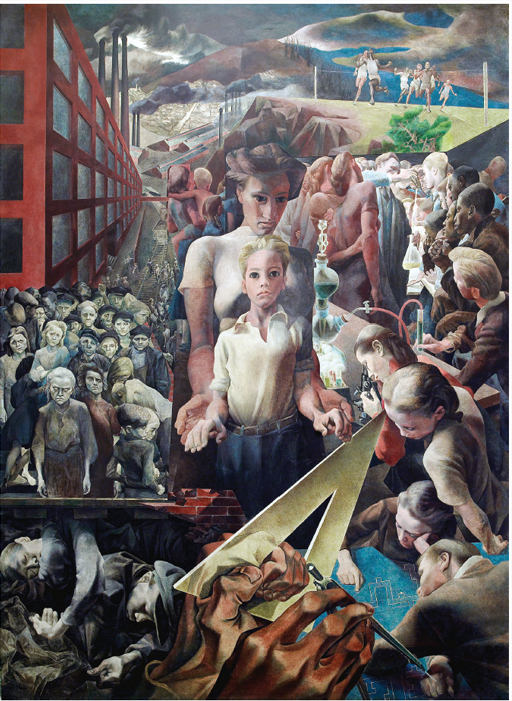

The mural programme launched by the post-revolutionary Mexican state provided a compelling model of how the arts in the United States might be both maintained and stimulated during the Depression era, when the Democratic government under Franklin D. Roosevelt launched the New Deal with a commitment to large-scale federal spending. An estimated $40 million was spent on producing art for public buildings, including murals in federal buildings from schools through to post offices, like that in Symeon Shimin’s Contemporary Justice and the Child (Figure 15) (Hemingway, 2002, pp. 75–100, 147–88).

As a medium frequently linked to revolutionary politics in the 1930s, muralism also became the cultural benchmark for Latin American anti-imperialist struggles thereafter. When Salvador Allende’s socialist government took power on the back of a popular mandate against United States influence in the early 1970s, there was a wave of political murals put up in support of his radically democratic policies. Likewise, when the Sandinistas took power in Nicaragua in 1979, after the country had been a client state for economic interests in the United States for years, it was only a matter of time before public walls were covered with murals in support of a popular democratic government that represented the genuine interests of its people (Figure 16) (Craven, 2002, pp. 117–75).

In the late 1960s, when the civil rights movement mobilised African-Americans and Latinos in the ghettoes and barrios of cities in the United States, the country underwent a mural renaissance, from the bottom up rather than from the top down, organised within the communities themselves (Figure 17) (Cockcroft, Weber and Cockcroft, 1977).

Significantly, the example set by los tres grandes lives on in Mexico itself, despite the gradual decline of muralism after 1968 when the government sought more neo-populist forms of propaganda to contain the political fallout from the Tlatelolco massacre in the build-up to the Olympic Games (Coffey, 2012, p. 14). Rafael Cauduro’s stairway murals in the Supreme Court of Justice (next to the National Palace on the Zócalo) are a case in point and a clear statement of the contemporary political resonance of the medium. Finished in time for the centenary of the beginning of the revolution, the murals dramatise the ways in which the Mexican state has systematically repressed civil liberties and has regularly deployed paramilitary forces against its civilian population since Tlatelolco, when hundreds of demonstrators were killed.

If you would like to, you can see Rafael Cuaduro’s mural scheme on this page under 'Suprema Corte de Justicia': Murales [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] (make sure to open the link in a new tab/window).

Originally conducted under the ‘dirty war’ backed by the United States, this violence has more recently been enacted in the name of the ‘war on drugs’. The burgeoning narcotics industry is itself a by-product of the levels of poverty in contemporary Mexico that are in part related to neo-liberal treaties such as the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which has opened up the country once again to the economic interests of the United States, this time under the guise of modernisation and the impact of globalisation. So, despite the decline of muralism in Mexico in the last half a century, Cuaduro’s mural scheme demonstrates that the tradition of monumental wall-painting pioneered by artists such as Rivera in the interwar period lives on in the present.