Who, where and when: getting to know Classical terms

This first introductory article provides a brief overview to help people who may not be familiar with studying the Classical world feel more ‘at home’ with references to dates, names, places and terms. If you’re familiar with these aspects, use the menu below to take a look at the intermediate level articles exploring ‘The Histories’ in more detail.

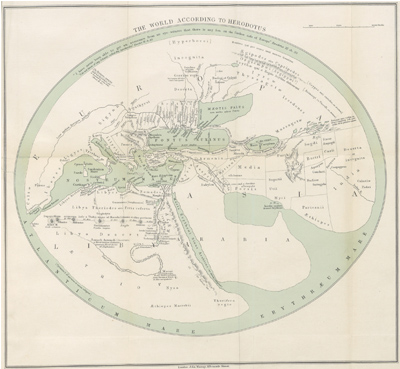

Image taken from page 387 of 'Herodotus: the text of Canon Rawlinson's translation, 1897

Image taken from page 387 of 'Herodotus: the text of Canon Rawlinson's translation, 1897

Names, places and maps

Many Greek names have more than one English equivalent. For instance, you will find Kyros as well as Cyrus, Aegyptos as well as Egypt. The reason is that there are different conventions for transliterating words from Greek into the English (Roman) alphabet. At the OU we generally use ‘Latinised’ spelling (eg ‘c’ rather than ‘k’, ‘ae’ rather than ‘ai’) and the more familiar English names where possible (Achilles not Akhilleus, Athens not Athenae). The important thing is to be consistent.

We sometimes use Greek or Latin terms, usually because there is no exact English equivalent. For example, the 'agora' refers not only to the marketplace in Greek cities but also to the place of assembly.

As you read the Herodotus narratives, you will notice there are no contemporary maps. Very few maps survive from the ancient world generally; moreover, they do not seem to have been widely used. In Book 4. Ch. 36-37, Herodotus ‘laughs at’ the maps produced by his contemporaries that divide the world into two regions of equal size.

In Book 5 Ch. 49-52 a character turns up with ‘a bronze picture, on which the whole world was engraved’, arguably the first historical ‘map’ in literature. Herodotus invites his readers to reflect on how the map is used to argue in favour of conquest and juxtaposes his own textual representation of the same space.

Cartography developed as a science much later, during the period of ‘discovery’ (15 - 16th century AD). Instead geographical knowledge in the ancient Greek world was primarily mediated through literary texts, such as Herodotus’ ‘The Histories’. The map illustrating this article is from a translation of 'The Histories' published in 1897, held at the British Library, London. One aim of the Hestia project is to create maps out of Herodotus’ text and use them to rethink our conceptions of geographic space.

Years

At the OU, course teams have opted for BCE (‘Before the Common Era’) and CE (‘Common Era’) to refer to dates (using them in the same way as the more traditional BC and AD, meaning Before Christ and Anno Domini or ‘in the year of our Lord’). Many people continue to use BC and AD instead. Either convention may be adopted, but when writing it’s best to be consistent. In the Herodotus OpenLearn Collection, we have decided to use BC/AD.

If you’re new to thinking about dates from the Classical period, remember that BC years (as opposed to AD years) count backwards. Browse along the Timeline to get a feel for some of what happened between 1250 and 100 BC, from roughly the date of the Trojan War to Roman domination of the Mediterranean, Europe and beyond.

Ancient terms and taking it further

We sometimes use Greek or Latin terms, usually because there is no English equivalent, such as agora (the marketplace in Greek cities). When writing, the convention is to put these words in italics.

You may find it interesting to explore more ideas about Greek or Latin roots in the English language - it can make a fascinating study and there are plenty of places to look on the Internet.

Visit Wikipedia for a basic summary of the language of the Ancient Greeks, and the Open University 'Reading Classical Greek' taster materials.

Rate and Review

Rate this activity

Review this activity

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Activity reviews