In this third intermediate activity in the OpenLearn Herodotus Collection, we suggest you take a look at two different annotations for the first few chapters in ‘The Histories’, Book 1. One is RapGenius, an online ‘crowdsourced annotation’, the other is the academic authoritative work by How and Wells, available via Project Gutenberg or the Perseus Project.

Rap Genius: where's the 'authority' in online collaboration?

Rap Genius is ‘dedicated to the crowdsourced annotation of music, news, literature, history, and just about any other text you could imagine.’ There is a translation of ‘The Histories’ Book 1 and the first ten chapters have been annotated.

Review the Rap Genius annotations by opening a separate browser window alongside the ‘raw’ Hestia texts and map references. Use the <<previous 1.2 next >> at the foot of the text pane to move between chapters.

King of Lydia shows his wife to Gyges (Herodotus, Book 1, Ch.9), by William Etty (1787 - 1849)

King of Lydia shows his wife to Gyges (Herodotus, Book 1, Ch.9), by William Etty (1787 - 1849)

How can we be sure that these annotations are from a credible source? What are the credentials of the RapGenius project in academic circles? How does the Internet support our enquiry into the Classical period? In the case of artists, how does illustration influence our ideas and interpretations?

When undertaking any serious study and research, questions of authority are crucial. There is a long tradition of academic and scholarly ‘commentary’ which, in the days of longhand writing and print production of theses was very different to ‘crowdsourcing’ and other online methods of sharing ideas in use today.

In Book 1, Chapters 1 - 5, Herodotus introduces some background to his great work, mentioning the roots of the ‘quarrel’ in the myths of Troy. It’s interesting to note in Chapter 5 that he states: ‘These are the stories of the Persians and the Phoenicians. For my part, I shall not say that this or that story is true, but I shall identify the one who I myself know did the Greeks unjust deeds, and thus proceed with my history, and speak of small and great cities of men alike.’

This even-handedness in his account, and especially his willingness to record alternative points of view, means that Herodotus’ ‘The Histories’ remain fresh and engaging, and prompt our further investigation. This style of narrative links with our discussion on Historiography in 'Classical Studies: more than the words'.

Academic commentary: How and Wells

Now try doing the same with some of the commentary from the scholarly authority on Herodotus, WW How and J Wells. This is available in full from the Gutenberg Project, where it may be downloaded as a very large PDF, as well as the Perseus Project. This may seem quite challenging at first glance, since the authors use the Greek words and alphabet, alongside their English commentary.

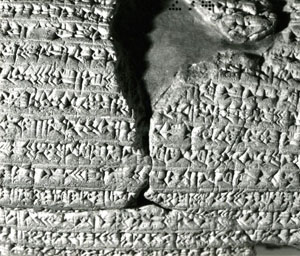

Extract from the Cyrus cylinder, an account of the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus, 539 BC

Extract from the Cyrus cylinder, an account of the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus, 539 BC

Although 'The Histories' was written on papyrus, other writings have been found on clay tablets, for example the Cyrus Cylinder, illustrated here as an example of cuneiform Babylonian in 539 BC. The Cyrus Cylinder provides valuable cross-references for some of Herodotus' narratives. Part of it is written in the 'voice' of Cyrus himself 'I, Cyrus, king of the world . . . '. Visit the British Museum online collection for more information.

Before looking at the How and Wells commentary, take a quick look at a passage from 'The Histories' you’re already familiar with, on the HestiaVis website. Browse it again in English, then try switching to the Greek version. Even if you have no knowledge of Ancient Greek, it may be interesting to browse for familiar words or characters in the Greek version. For guidance about using HestiaVis, visit the 'Hestia Project map and partners' resources'.

Academics and scholars tend to use the original Greek text at times when writing a commentary. Why do you think this is? If you have knowledge of another language, are there occasions when you cannot find an accurate translation, or resort to body language for meaning? We can all think of words that have been ‘adopted’ into English, or English words which have become common usage in other languages.

Now take the plunge and explore what How and Wells have to say, by opening three browser windows and switching between three familiar chapters:

How and Wells comment on Book 1 Ch. 6-8

Switch between Greek and English on the Hestia map

Compare these with the Rap Genius commentary, and very different user interface.

In dealing with this period of history, which reaches back into an era before events were written down and preserved, it is essential for us to have credible source material and to cross-reference our evidence carefully.

The advent of the Internet makes this easier in some respects, through crowdsourced annotations and academic works being available online as we’ve seen in this activity. Always check your sources for credible citations and evidence. When referring to online sources, always credit the author, creator and/or copyright holder.

Rate and Review

Rate this activity

Review this activity

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Activity reviews