We have selected the Croesus story from Herodotus Book 1 chapter 6 - 95 as the basis for this intermediate activity in the OpenLearn Herodotus Collection. Our aim is to help you start enquiring into how the Herodotus narrative is linked with places in the Classical world and later writings. As well as browsing the narratives, the story forms a useful way to explore the theme of historical ‘truth’ and the challenge of ‘chronology’. You may like to take a look at the Timeline and Introductory articles in the Herodotus OpenLearn Collection to put some of the narratives into context.

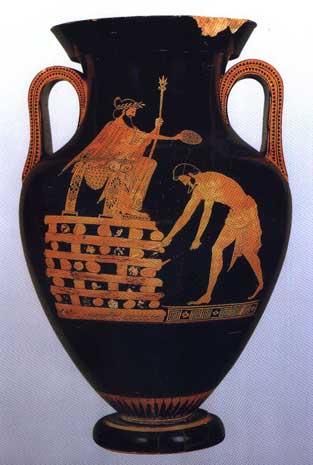

Croesus at the stake. An Attic red-figure amphora, c.500 - 490 BC, Louvre, Paris

Croesus at the stake. An Attic red-figure amphora, c.500 - 490 BC, Louvre, Paris

The account of Croesus’ downfall (and accompanying path towards self-knowledge) is often called the ‘Lydios logos’.

'Logos' is impossible to translate precisely into English. It can suggest ‘word’, ‘argument’ or an ‘account’ (as in: ‘In the beginning was the word [logos]’, John 1.1). 'Logos' derives from the verb 'legein', ‘to speak’, and implies ‘that which was said’. It seems to be in this sense that Herodotus uses it. He often prefaces the ‘logoi’ he relates with ‘the Athenians say’, or ‘the Persians say’. He sometimes weighs up the merits of divergent ‘logoi’, or simply places them alongside each other for the reader to judge and decide between.

As discussed in the Herodotus OpenLearn Collection Introductory article 'Understanding Classical terms' there are no contemporary maps to refer to, and many people studying this period find a similar challenge when trying to establish a sense of chronology as a context for events. Since mediaeval times scholars, academics, researchers and historians have tried to integrate a timeline into the stories told in ‘The Histories’, alongside other narratives, texts and archaeological evidence.

Now is your chance to join them by reviewing some of the events of the period with references to Herodotus’ texts and place references.

Read the description of the famous Attic red-figure amphora, c.500 - 490 BC, depicting Croesus on his pyre, on the Louvre, Paris website.

Chronology in ancient Greece

Though the four-yearly cycle of the Olympiads provided some orientation, the Greeks didn’t really have a common system for recording dates. See, for example, Thucydides, 'The Peloponnesian War', Book 2, Ch. 2:

“The 30 years' truce which was entered into after the conquest of Euboea lasted 14 years. In the 15th, the 48th year of the priestess-ship of Chrysis at Argos, in the Ephorate of Aenesias at Sparta, in the last month but two of the Archonship of Pythodorus at Athens, and six months after the battle of Potidaea, just at the beginning of spring, a Theban force . . .”

Local time systems were used, notably based on the names of individuals who held some political magistracy such as eponymous archons (chief magistrates in various Greek city states) or who were in religious office. Extrapolating from these individual records, we can provide rough BC dates for the majority of events that take place in Herodotus’ ‘The Histories’.

Herodotus counts by generations, for example the kings of the Mermnads dynasty, ruling from c.680 - 547 BC in Lydia, form the background for Book 1: Gyges, Ardys, Sadyattes II, Alyattes and finally, his son Croesus who we look at in some detail. It has been argued that generational calculation was a standard way for early historians to come up with dates, and many students find this lack of a clear chronology very frustrating.

You may be interested in looking at Eusebius of Caesarea’s chronicle (c.311 AD), translated c.380 AD by Jerome, which forms a very early attempt to synchronise events to provide an absolute timeline.

Another source for Greek chronology is the Parian Marble (Parian Chronicle or Marmor Parium), held at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford since the 17th century AD. View scans of the marble and translations here (NB: Chrome, Safari or IE browsers only).

Herodotus' narratives vs. known chronology: what was possible?

There are three main events in the first book of ‘The Histories’: Solon’s visit to Croesus in Sardis, Croesus' consultation of the oracle at Delphi, and the fall of Sardis. As you explore the texts and places on the Hestia map, set aside anxieties over chronology and try to focus on what is being said. After all, there is considerable scope for inconsistencies when working with ancient literature and Herodotus offers us several ‘sides’ to a story.

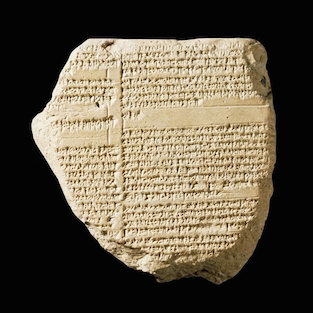

Cyrus cylinder, British Museum

Dates are always a challenge when discussing Herodotus’ narratives, for example the dates we know for Solon don't let him visit Croesus, but there are also problems with interpretation such as the rescue of Croesus from the burning pyre or the death of Cyrus.

Cyrus cylinder, British Museum

Dates are always a challenge when discussing Herodotus’ narratives, for example the dates we know for Solon don't let him visit Croesus, but there are also problems with interpretation such as the rescue of Croesus from the burning pyre or the death of Cyrus.

So, how far do the events in ‘The Histories’ fit in with other evidence from contemporary sources and archaeology? Did Croesus die in 547 BC? What happened to Croesus when Sardis fell? Could Solon have visited Amasis II in Egypt? Did Solon visit Croesus in Sardis?

Although 'The Histories' was written on papyrus, other writings have been found on clay tablets, for example the Cyrus Cylinder, illustrated here as an example of cuneiform Babylonian in 539 BC. The Cyrus Cylinder provides valuable cross-references for some of Herodotus' narratives. Part of it is written in the 'voice' of Cyrus himself 'I, Cyrus, king of the world . . . '. Visit the British Museum online collection for more information.

It is generally agreed by academics and scholars that Cyrus took Sardis in 547/546 BC, by comparing evidence from the Cyrus cylinder, Herodotus' 'The Histories', and the archaeological record. Where they don't necessarily agree is in what happened to Croesus. Was he killed on the burning pyre, or did he become a trusted advisor to Cyrus?

Everyone also assumes that Solon couldn't have visited Croesus in Sardis during his period of travelling. The generational chronology and evidence from other sources make it impossible.

Croesus was definitely ruler of Sardis, and Cyrus definitely captured Sardis. As you explore the texts, think about the interactions Herodotus describes, such as those between Solon and Croesus, and between Croesus and Cyrus. These are the puzzles to think about. How is the story is told? Why does Herodotus include these stories?

For a short introductory commentary to place Croesus’ life in context, visit the well-referenced Livius.org website for a summary of the Mermnad Dynasty.

How did Croesus die and when did Sardis fall?

Skim read some of Herodotus’ narratives in Book 1, to get a ‘feel’ for the style of his writing. Concentrate on reading what he says about Sardis (mentioned 119 times, but just read the chapters in Book 1 for now). Refer to the Project map and partners' resources for guidance in using the Hestia texts. Now read the commentary from Livius.org where the author outlines the problem.

Nabonidus Chronicle, British Museum, London

Nabonidus Chronicle, British Museum, London

“For Greece, the sequence of events in what we call the 6th century BC is more or less known from Herodotus of Halicarnassus. 'The Histories' contain a general account of the history of towns like Sparta, Corinth, and Athens, and many synchronisms: people who knew each other, battles, etc. It is obvious that Herodotus uses two chronological systems, which appear to be out of step for a generation, but his outline of Greek history, the relative chronology, is pretty clear. As we have seen though, it is difficult to establish an absolute chronology, to make a match between the events and the number of years. However, the situation is not entirely hopeless. It is clear that the rule of Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, coincided with the reign of the Persian king Cambyses, and that Polycrates' downfall occurred after the double coup d'etat in Persia that took place in 522 BC. We can also be reasonably certain that the death of Polycrates occurred in 522-518 BC. Finally, there is another synchronism between Greek and Persian history: the conquest of Lydia and the death of its king Croesus. This event is mentioned by Herodotus and several other authors, as taking place between 550 BC (when the Persian leader Cyrus the Great overcame his Median overlord Astyages) and 539 BC (the year in which Cyrus took Babylon).”

The commentary goes on to introduce the Nabonidus Chronicle to support the narratives in Herodotus. Notice the example of contradiction, even amongst the carefully cited sources of Livius.org, where in one section, the author says there's no evidence that Croesus was killed when Sardis fell, but then later takes it back and says there's a new consensus emerging that he was.

To help your analysis and exploration of ‘The Histories’, draw up a table to keep notes of key people, places and points discovered in the different narratives. Although chronology is a challenge, as we have discussed, put in a few connections and dates that are certain. Refer to the Timeline to cross-reference your own observations. Leave an extra column for your own notes and references to the source of the information eg ‘Histories’ Book/Chapter, Livius.org commentary/web address etc. It is always essential to ‘cite’ all references, in particular from online sources.

Reflect on how reading the writings of Herodotus and reviewing the commentaries by other reliable sources makes you a ‘researcher’ using ‘open enquiry’, rather than a ‘consumer’ of history as a set of ‘facts’.

How does this make you feel about the study of history?

Rate and Review

Rate this activity

Review this activity

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Activity reviews