Historiography and ancient literature: it’s more than words

This second introductory article provides some ideas about how to frame your exploration of the writings of Herodotus in the context of other ancient works of literature and history. As you explore the writings of Herodotus in the OpenLearn Collection, think about the issues raised below, summarised from those posed by the OU A219 Course team. Bookmark this article and come back to review the questions, once you have spent some time looking at the other resources and exploring the map.

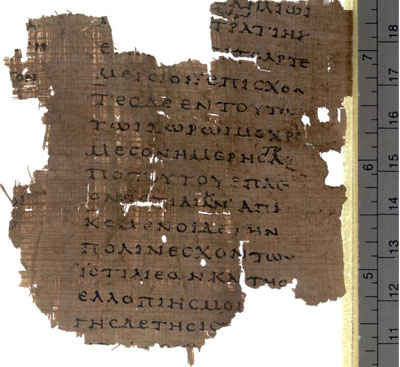

Fragment from Herodotus' 'The Histories', Bk 8 on papyrus, early 2nd century AD

Fragment from Herodotus' 'The Histories', Bk 8 on papyrus, early 2nd century AD

How to read literature

The very explicitness of literature – the fact that you can read it – can be deceptive. Let’s consider Homer, who chose to write epic poetry to describe Greek society. The nature of Homer's society is a hugely contested issue. Is it contemporary society Homer is describing? Is it an earlier kind of society that Homer (just like us) explores on the basis of knowledge that has somehow come down to him? If it is, does the fiction still tell us something about real societies? Moreover, what sort of voice is Homer's? Was he part of an elite? In that case, how is what he says biased by this fact? Or was he influenced by what his audience wanted to hear? Along with the vast majority of ancient voices we hear through literature, Homer's is a male voice; and even most of the far fewer female voices we do hear are written down or even invented by men. The point may be extended to say that we only hear the voices of the literate, a small minority in the ancient past, and so literature can never be representative of the totality of society. As ever, unmediated access to the ancient world is impossible.

Herodotus is the focus for this OpenLearn Collection, but if you would like to find out more about Homer, Elton Barker and Joel Christensen’s ‘Homer: A Beginner’s Guide’, published by OneWorld, makes an excellent starting point.

What about historiography?

Historiography is the writing of history, another type of source that relies on words. Where literature is often associated with art, history-writing today is associated with truth. As a result, it's a natural instinct to read ancient historians with the expectation that they are more reliable sources than literature. To a degree, that's fair enough. Most ancient historians took pains to distinguish themselves in one way or another from poets like Homer. However, the character of these distinctions varied greatly, and rarely matches the distinctions most of us would make today between history and literature.

For instance, the association of historiography and truth, while known, is rather different in the ancient world. Tacitus (a Roman born in 56 AD and a sophisticated historian if ever there was one) starts his most famous work, 'The Annals', with a line of verse. Herodotus, considered to be the first historian, is at the centre of an enormous debate: some scholars think that he simply made up large chunks of his work, and no one thinks that everything he says can be taken as fact. He even says himself: 'As for myself, although it is my business to set down that which is told me, to believe it is none at all of my business. This I ask the reader to hold true for the whole of my history.' Herodotus 7.152

Some ideas for becoming an historian

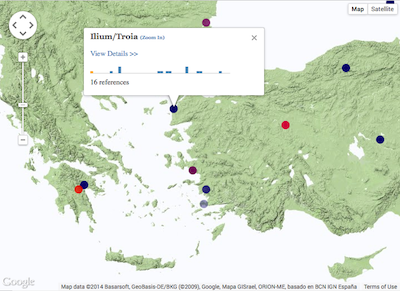

Screengrab from Hestia Project map

Screengrab from Hestia Project map

The word ‘history’ derives from the Greek word ‘historia’ (or historiê in some dialects, including Herodotus’), which means ‘enquiry’: to understand the past, you must research it. Herodotus ‘reproduces’ that sense of enquiry in the very way that he structures his material. You’ll find that frequently he puts views into the mouths of his historical agents, including competing accounts of the same event. As a result, by reading through his account and having to judge the veracity of the statements from different witnesses, we too engage in ‘enquiry’ and become historians.

Even in the 5th century BC, history was as much about what was most likely, based on one's powers of reasoning and knowledge of the world and the way it works, as about truth. As you explore the writings of Herodotus in the OpenLearn Collection, ask yourself what you think Herodotus' aim was in writing and how reliable you consider his evidence to be. Start thinking about history as ‘an enquiry’, rather than a fixed set of facts ‘served’ up by a particular writer.

It might be helpful to create a table to jot down your thoughts and keep it beside you whilst you read the extracts and explore the map. Tabulate the names of people and places with references to go back to, and double-check what Herodotus wrote compared with other writers you may ‘meet’ during your research, such as Plutarch.

Start your research by looking around the Hestia project map. The Hestia project links places based on references in Herodotus’ ‘The Histories’. For more ideas about how to use the map interface, look at ‘Hestia Project map and partners’ resources’ [URL] where there are also some suggestions for finding other sources to support your research.

The OpenLearn Collection includes a Timeline. Browse the events and follow some of the links to the map, get a ‘feel’ for the period Herodotus was writing about, and where some of the key places were.

You will notice that some dates on the Timeline are ‘estimates’. Why do you think we cannot provide an accurate date?

Herodotus introduces the possibility for ambiguity at the very beginning of his narrative, when he mentions the Fall of Troy (Ilium), with the traditional date being 1250 BC: Book 1 Ch. 5 'These are the stories of the Persians and the Phoenicians. For my part, I shall not say that this or that story is true, but I shall identify the one who I myself know did the Greeks unjust deeds, and thus proceed with my history, and speak of small and great cities of men alike.'

Rate and Review

Rate this activity

Review this activity

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Activity reviews