1.2 The cult of Amphiaraos

In this course, you will be thinking in depth about the figure of Amphiaraos, whose cult site (that is, the main location where he was worshipped) at Oropos was popularly associated with healing by the late fifth century BCE (see Map 1). However, Amphiaraos was not the only divinity associated with this quality: there were more ‘popular’ figures who shared this same attribute. The most famous god associated with healing was arguably Asklepios, who had a major cult site at Epidauros in the Peloponnese, among other places (see Map 1).

Study note: names of Greek places and people

Many Greek names have more than one English spelling. For instance, you will find Asclepius as well as Asklepios, Aphaea as well as Aphaia and Herodotus as well as Herodotos. The reason is that there are different conventions for transliterating words from Greek into the English alphabet.

In this course, ‘Hellenised’ spellings are generally used, for example, ‘k’ rather than ‘c’, ‘ai’ rather than ‘ae’, and ‘os’ rather than ‘us’ at the end of names: Asklepios, Aphaia, Herodotos. These ‘Hellenised’ spellings closely reflect the way these names were spelt in ancient Greek. Elsewhere, you will often find modern authors and translators using ‘Latinised’ spellings, however: ‘c’ rather than ‘k’, ‘ae’ rather than ‘ai’, and so on (Asclepius, Aphaea, Herodotus).

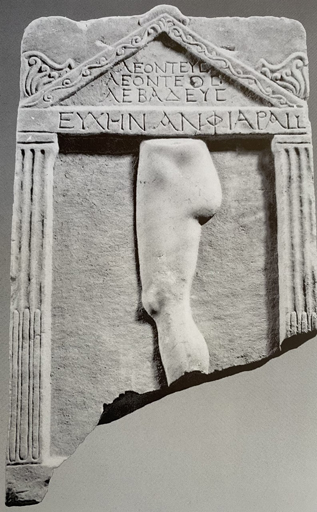

At Asklepios’ sanctuary at Epidauros, temple officials aimed to promote the healing capabilities of the god to visitors by setting up stone inscriptions which recorded the experiences of individuals and the cures they received. These cures contain several fantastical elements and recount miraculous tales of Asklepios’ healing of both humans and even objects. Although we do not have comparable tales from the Amphiareion which describe Amphiaraos’ medical expertise, we do have text-bearing dedications (that is, religious objects often erected within religious settings to honour a divinity – such as the one depicted in Figure 3) which clearly relate to acts of healing. Such evidence, which you’ll have the opportunity to explore later in this course, can help us to learn more about the activities of individuals who visited the god’s sanctuary to seek a cure.

Different divinities, then, had different ways of being consulted for medical treatment. In Amphiaraos’ case, surviving pieces of ancient evidence make it clear that the ancient Greeks communicated with him through the medium of dreams. This doesn’t mean that Amphiaraos spontaneously visited people as they were tucked up in their beds at night, but that those seeking the god’s help made the journey to his sanctuary at Oropos where they slept overnight. This process is also known as incubation.