5 Enlightenment and the classics

The civilisations of ancient Greece and Rome formed both a common background and a major source of inspiration to Enlightenment thinkers and artists (see Figure 4). The dominant culture of the Enlightenment was rooted in the classics, and its art was consciously imitative and neoclassical. English literature of the first half of the century was known as ‘Augustan’ – that is, comparable to the classic works of the age of the Roman emperor Augustus (27 BCE-CE 14), notably Virgil and Horace and, from the late republican period, Cicero. Augustan literature was characterised by moderation, decorum and a sense of order. The Augustan poet would use classical allusion, authority and satire to convey a deeply reasoned wisdom. The verse of Alexander Pope was quintessentially Augustan in its compressed insights into mankind, expressed in controlled, balanced verse. In his Imitations of Horace, Pope paid tribute to his admired classical model. Horace, he wrote,

Will, like a friend, familiarly convey

The truest notions in the easiest way.

From the grounding in Latin and Greek which formed the basis of their education, the wealthy and well connected of the eighteenth century were at home with the poetry, history and philosophy of the ancient world. In the words of Samuel Johnson, ‘classical quotation is the parole [password] of literary men all over the world’ (Boswell, 1951, vol.2, p. 386). When Johnson dined in company with the disreputable politician John Wilkes, neither thought it out of place to discuss a disputed passage in Horace. James Boswell, Johnson's companion and biographer, and son of a Scottish law lord, the Laird of Auchinleck, recalled how in his youth he had associated well-known passages from classical verse with the natural, indeed ‘romantic’ beauties of the estate:

The family seat was rich in natural romantic beauties of rock, wood, and water; and … in my ‘morn of life’ I had appropriated the finest descriptions in the ancient Classicks, to certain scenes there, which were thus associated in my mind.

(Boswell, 1951, vol.2, p. 131)

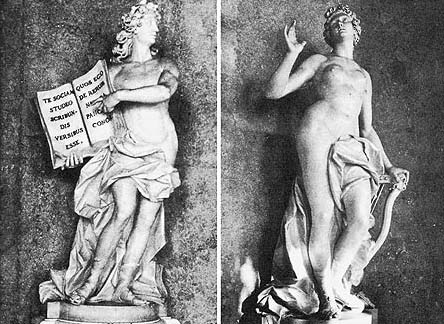

Across Europe the social elite studied antique statuary, either by viewing originals or copies close to home or by going on the ‘Grand Tour’ to Italy, to view original sculptures and buildings in Rome itself. To participate in such a tour, to be well versed in the ancient languages and to commission buildings and paintings in the antique style – a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, a mansion by Robert Adam – signalled membership of a class that felt itself to represent the very best of western civilisation and that surrounded itself with classical statuary or neoclassical artefacts as emblems of wealth, status and power (see Figure 5).

Men and women of the Enlightenment related to, empathised and identified with the ancient world, more particularly with the world of classical Rome, believing that eighteenth-century Europe had achieved a similar peak of cultural excellence. In the words of Edward Gibbon (1737–94 – see Figure 6), author of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–88), contemporary Europe was ‘one great republic, whose various inhabitants have attained almost the same level of politeness and cultivation’ (Gibbon, 1954, p. 107). By contrast, eighteenth-century Europe tended to reject as ‘barbarous’ or ‘Gothic’ the Middle Ages, which it called the Dark Ages, the entire millennium from the fall of Rome in the fifth century CE to the Renaissance in the fifteenth.

Contrasting the perceived uncongenially of the Middle Ages with the perfection of republican and imperial Rome, Gibbon looked back as the inspiration for his Decline and Fall to the moment in his Grand Tour when he sat musing in the ruins of the Forum at Rome, ‘whilst the barefooted friars were singing vespers in the Temple of Jupiter’ (quoted in Lentin and Norman, 1998, p. viii). The contrast between the noble ruins of pagan antiquity and the ‘barefooted friars’ suggested a tension between classical values and the Christian: Gibbon blamed the forces of ‘barbarism and religion’ for their contribution to the fall of the Roman empire (Lentin and Norman, p. 1074).

The German philosopher Kant summed up the Enlightenment view of the Dark Ages as ‘an incomprehensible aberration of the human mind’ (quoted in Anderson, 1987, p. 415). In 1784, defining Enlightenment as ‘man's emergence from his self-incurred immaturity’, Kant argued that people should cease to rely unthinkingly on authority and on received wisdom; they should have the courage to think for themselves. ‘The motto of enlightenment’, he declared, ‘is therefore Sapere aude! Have the courage to use your own understanding’ (Eliot and Whitlock, 1992, p. 305). The motto was taken from Horace.

The classics, then, provided for Enlightenment thinkers not just a standard of artistic perfection for emulation but also an independent set of criteria against which to measure, compare and contrast the past and contemporary world, and a spur to thought and action. To the particular delight of the anti-clerical philosophes, the classics suggested a secular alternative to Christian modes of thought and expression. In their constant assaults on conventional religion, they found in the ancient philosophies of Stoicism and Epicureanism, or an eclectic mix of both, an attraction and a pedigree that predated Christianity and suggested rational or at least dignified alternatives for people to live by – and indeed to die by. In the deaths of Socrates and Seneca, the classics offered a noble tradition of suicide, a mortal sin in the eyes of the Church. The dying Hume, claimed with apparent equanimity and very much in the spirit of the Romans that he had neither fear of death nor belief in a future life. The classics were also used to legitimise modern ideas on society and culture in a way that suggested Enlightenment ideas had universal force and relevance, being rooted in the oldest and greatest of civilisations.

Summary point: for Enlightenment artists and thinkers, classical antiquity provided a standard of greatness, a symbol of power and a secular legitimisation of their own forward thinking.

Exercise 5

Turn now to your AV Notes (click on 'View document' below), which will direct you to watch section 3, ‘The classics’. When you have worked through this section of the video and attempted the exercise in the notes, return to this course.

Click on 'View document' [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] to read the notes and exercise for video 3

Click on the blank screen below to start playing video 3 'The classics'