1 Overview

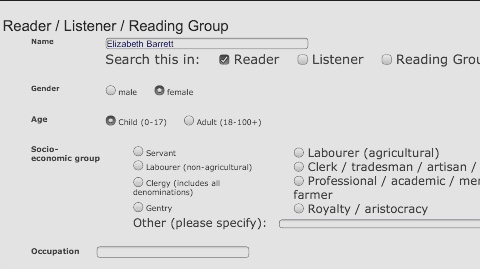

This course looks at specific examples of the reading and responses of two great British women writers and intellectuals: the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861), and the art historian, critic and essayist Vernon Lee (pseudonym of Violet Paget, 1856-1935).

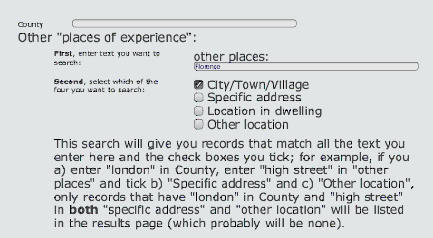

The author of Aurora Leigh (1857) and Sonnets from the Portuguese (1844), Barrett Browning was one of the leading poets of mid-Victorian Britain; such was her popularity and critical standing that on the death of William Wordsworth in 1850, she was considered for the post of Poet Laureate, an appointment which eventually went to Tennyson. Writing a generation later, Lee was less feted in her lifetime than Barrett Browning, but her astonishingly original literary output – over 40 books on a wide range of subjects from aesthetics to music and biography to literary criticism – influenced writers as diverse as Jack London, Edith Wharton and Virginia Woolf. Building upon Red_1 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , which explained the range of data available to historians of reading, and Red_2, which looked at how the site can be used to map the reception history of a specific book, this course shows how examining the evidence of reading of two famous writers can tell us a great deal about their own intellectual lives, and that of the times in which they lived.

Living in an era when women were largely denied the benefits of a university education, both Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Vernon Lee were taught at home with the aid of tutors, and developed their formidable intellects through voracious and often systematic reading at home.

Both had the run of their parents’ libraries, and as child prodigies, displayed a prodigious gift for languages: French, German, Italian, Greek and Latin, and in Barrett Browning’s case, Hebrew as well. A letter from Elizabeth Barrett to her then fiancée Robert Browning in January 1846 also suggests the ways in which her father tried (and failed) to control her teenage reading (and raiding) of his library for radical literature:

‘Papa used to say “Don’t read Gibbon’s history – it’s not a proper book – don’t read Tom Jones & none of the books on this side, mind – so I was very obedient & never touched the books on that side & only read instead, Tom Paine’s Age of Reason & Voltaire’s Philosophical Dictionary, Hume’s Essays, & Werther, & Rousseau, & Mary Wollstonecraft…which did as well’.

For both women, reading became essential to their professional ambition and identity as writers, but they also had to contend with the dilemma of finding their own voice and establishing their names in an overwhelmingly male literary tradition: one that often assumed women to be consumers and not producers of great literature. In this tutorial, we will investigate some of the reading and response of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Vernon Lee, and see how they shaped themselves as writers through their reading.